Chapter Nine

Taking Control: Battling Obesity

through Dietary Change

and Stress Management

As we have discussed in previous chapters, obesity is epidemic in the US and abroad. Obesity and obesity-related illness account for nearly 190 billion dollars of annual healthcare expenditure in the US alone. Obese women are at particular risk for cardiovascular disease and must do more to moderate their risk. Engagement is critical. In the last chapter, we discussed the importance of lifestyle modification — particularly exercise — in reducing risk.

However, exercise is just one, albeit important, piece of the puzzle. Obesity is clearly related to caloric intake, lifelong habits and dietary choices. Women must accept individual responsibility for their own cardiovascular health and partner with their healthcare providers in order to effect change. Managing weight with diet and exercise is not an easy task and requires dedication and hard work. Dietary changes often require support of family and friends and it is typically necessary for patients to ask family to make changes with them as they embark upon a weight loss journey. More importantly, patients must change habits in order to maintain weight loss. Numerous studies on diet and weight loss have indicated that long-term maintenance of weight loss can be quite challenging and results have been less than ideal.1, 2 In a meta-analysis of obese individuals who participated in structured weight loss programming, most only maintained approximately 23% of their total weight loss at year five.3 Data from the National Weight Control Registry has been analyzed over the years and has helped physicians and nutritionists to identify characteristics that may predict those that are more likely to be unsuccessful with maintenance of weight loss.4 The following characteristics are associated with those that are more likely to be successful with weight loss over the long term when employing a strategy of diet modification5:

(1) Concomitant participation in high levels of physical activity

(2) Consuming a diet that is low in calories and fat

(3) Never skipping breakfast

(4) Regular self monitoring of weight

(5) Maintaining a constant eating pattern — no binging

(6) Catching “slips” early

Interestingly, studies from this same registry indicated that weight loss after any significant “medical event” seemed to help to facilitate long-term weight control.6 When patients were asked, nearly 83% of those in the registry reported a significant event as the trigger for their engagement in dietary plans for weight loss. Triggering events were found to be medical in 23%, reaching an all-time-high weight in 21% and seeing a picture or reflection of themselves in 12%.6 Medical triggers for weight loss were associated with greater total weight loss and better weight maintenance over the long term. Many of these medically motivated patients in the registry were those who had suffered a cardiac event and were told to “lose weight” by their cardiologist or internist after the acute phase of the illness was survived. This data suggests that the time following a medical trigger may be a very opportune time for intervention with patients to promote more successful long-term weight loss. Physicians and other healthcare providers should utilize this time to actively influence patients and families to initiate lifestyle changes and improve outcomes. As we have seen in previous chapters, obesity seems to be a particularly significant modifiable risk factor in women and the reduction of BMI may result in lower rates of cardiovascular disease and acute cardiac events.

Just as with daily exercise and physical activity, it is essential to empower women with the knowledge they need to be successful. We must engage and motivate patients so that they are willing to actively participate in their care and in both the primary and (if necessary) secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Which diet is right? Offering guidance for improved cardiovascular outcomes

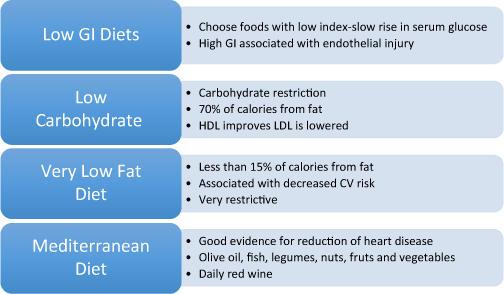

There are many choices when it comes to dietary regimens aimed at improving cardiovascular health and reducing body weight. Many of these diets have been well studied and outcomes are published in peer-reviewed medical journals. The American Heart Association has advocated a low fat diet with only 30% of calories from fat — however, this often results in high degrees of carbohydrate intake which can lead to obesity, insulin resistance and weight gain.7

(1) Low carbohydrate diets: Carbohydrate restrictive diets such as the Atkins diet have been practiced for many years.8 These diets rely upon carbohydrate restriction initially, followed by gradual reintroduction. In contrast to the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, diets such as the Atkins approach obtain nearly 70% of the daily calories from fat. When multiple studies involving low carbohydrate diets are reviewed, it is noted that HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol improves to higher levels while LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol and triglyceride levels are significantly reduced.9 Over time, total weight loss is not appreciably different from other dietary strategies. Unfortunately most trials involved small patient numbers and did not involve lengthy follow-up times so any real impact on cardiovascular mortality is difficult to determine in any statistically significant way.

(2) Glycemic index diets: The glycemic index (GI) is a measure of blood glucose response to intake of a particular carbohydrate type and the higher the blood glucose response, the higher the GI assigned.10 Studies have shown that diets with high values for glycemic index are associated with higher rates of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.11 It appears that diets that consist of foods that rapidly raise the blood sugar level may actually increase levels of free fatty acids and play a role in the induction of endothelial injury and the activation of coagulation through oxidative stress. Endothelial injury and hypercoagulability contribute to the process of plaque formation in the development of coronary artery disease.11 Although many of these diets have been effective in promoting weight loss, there are no clinical trials that have shown that diets that promote a low GI are associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular disease.

(3) Low fat diets: Very low fat diets (VLFD) are defined as diets that include no more than 15% of total calories from fat (with an equal amount of saturated and polyunsaturated fats). Many vegetarian diets rely on the very low fat concept. There does appear to be some association between the VLFD and decreased cardiovascular risk.12 This diet is often very restrictive and can be difficult for many patients to adhere to.

(4) Mediterranean diet: The Mediterranean diet has well-established evidence in the reduction of cardiovascular disease.13 In addition, there are large databases that have demonstrated that adherence to the Mediterranean-style diet is associated with a significant reduction in obesity.14 In general, the Mediterranean diet consists of olive oil as the principal fat, lots of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, and the primary protein in the form of fish. Meat and dairy intake is minimized and daily moderate alcohol consumption in the form of red wine with meals is encouraged.15 This type of diet has been associated with lower BMIs, lower fasting glucose levels, lower blood pressure and lower levels of circulating inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP). When elevated, all of these markers have been associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and death. Even in patients who have experienced a previous myocardial infarction, adoption of the Mediterranean-style diet has been associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiac death in these secondary prevention patients.16

Special dietary considerations in women

There have been numerous studies that have examined specific dietary changes in women and the impacts these changes have on cardiovascular disease incidence as well as cardiovascular-related deaths. Lessons learned from these studies that were conducted with only women subjects can provide important insights into how specific changes can make a difference in risk for disease.

For example, there has been much research done on the impact of dietary fats on heart disease. It has been proven that the intake of high quantities of trans fats is associated with higher risk for heart disease.17 Trans fats are synthetic fats that can give food a pleasing texture and taste. They are rarely found naturally but are easily produced by industry and are also found in hydrogenated oils. Trans fats are widely utilized in the fast food industry due to the fact that they are easy to produce in a cost-effective and profitable way. In addition, many crackers, cookies, cakes and fried foods contain trans fats. The FDA is currently considering legislation to ban or severely limit the use of trans fats in the food supply, given the high association of trans fats with cardiovascular disease.18

Figure 9.1 Common diet options and heart disease. CV = cardiovascular disease.

A study from the New England Journal of Medicine from 1997, evaluated the role of fat consumption in women and rates of heart disease.19 In this investigation, the relationship between dietary intake of specific types of fats — trans saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated and the risk of coronary artery disease was examined in women who were part of the Nurses’ Health Study database. Involving over 80,000 women, the study found that each increase of 5% of energy intake from saturated fat resulted in a 17% increase in coronary artery disease risk. Moreover, the intake of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats did not result in a statistically significant increase in cardiovascular disease risk. Most importantly, total fat intake was not associated with increased heart disease risk but replacing saturated fats with poly- and monounsaturated fats resulted in a 53% reduction in cardiovascular disease risk.17 The authors concluded that replacing saturated and trans saturated fats with mono- and polyunsaturated fats is more effective in preventing heart disease than simply reducing overall fat intake.

As we have mentioned earlier in the chapter, the Mediterranean diet has been shown to decrease cardiovascular mortality in both men and women. A staple of the Mediterranean-style diet is the consumption of nuts and legumes. Now, in addition to looking at the types of fats that are consumed, there are also studies that have been conducted in women to evaluate the cardiovascular benefits of nuts. In a study from Harvard published in 1998, researchers evaluated the effects of frequent nut consumption on women and their cardiovascular health. What they found was a powerful reduction in both fatal coronary heart disease and non-fatal myocardial infarction.20 In fact, women who consumed nuts more than five times a week had a 35% reduction in cardiovascular events as compared to those women who rarely ate nuts. Other studies such as the Adventist Health Study, also demonstrated a positive effect of nut consumption — nearly a 50% reduction in risk for cardiovascular disease.21

Data for dietary modification in the reduction of heart disease is compelling. While women cannot control their family history or genetic predisposition to disease, obesity- and diet-related risk are things that can be modified through engagement and dedication to change.

What is ultimately the right choice?

The right choice is ultimately the diet that brings success. Each individual must choose a diet and make a lifestyle change that they are able to adhere to and enjoy. As healthcare providers, we must make recommendations and help our patients choose the plan that will give them the best chance of achieving their goals. Diets that focus solely on elimination have lower success rates than those that focus more on including multiple healthy food choices. Lifestyle changes, such as diets, require support. As physicians and providers of healthcare to women, we must work to provide a network of support for our patients. This can be accomplished through routine follow-ups as well as the creation of patient-based support groups within the practice.

Research indicates that social support systems — particularly family support — can make an enormous difference in the success of any weight loss plan.22 As healthcare providers for women, it is essential that we involve families, including children and spouses, in any lifestyle modification plan. If we are able to involve and engage loved ones as well as the patient, we can facilitate changes in behavior that will assist in reducing cardiovascular death in women.

In addition to family support, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that internet and online support for weight loss programs is equivalent to the effects of face-to-face support groups.23 In fact, results from a study in 2004 show that a weight maintenance program based solely on internet interaction could sustain comparable long-term weight loss to those conducted in person or via telephone. The fact that alternative support opportunities exist allows us to provide even more options for our patients who wish to lose weight. The proliferation of online tools and the internet allows even those with limited access to transportation to take full advantage of the support systems that breed success.

What about stress and heart disease in women?

Stress has been identified as a significant risk factor for chronic disease for quite some time and has been associated with premature aging and increased risk for heart disease and stroke.24, 25 There is clearly a link between the mind and the body and exogenous life stressors have a negative effect on our bodies. While not much is known about the precise mechanism by which this occurs, at the molecular level cellular damage is mediated by shortened telomeres.26 Telomeres are caps on the end of chromosomes, which work to maintain chromosomal stability. It is postulated that shortened telomeres are associated with increased cellular damage and accelerated aging. Moreover, antioxidants have been found to protect against cellular damage via limiting the shortening of telomeres.27

We have discussed previously that women often find themselves under a great deal of stress. In one study, it was found that reported psychological stressors in a group of women was significantly associated with increased oxidative stress, shortened telomeres and reduced telomere function at the cellular level.28 In addition, women with increased stress were found to have one decade of additional biological age (at the cellular level). These findings may help explain how stress can significantly impact women’s risk for heart disease and stroke.

There have been other studies that have shown a significant association between increased perceived stress and risk of cardiovascular death. Shift work has been long associated with increased rates of stress and serves as a good model for clinical investigation of the effects of long-term stress on survival.29 A study published in Circulation in 1995 demonstrated an increased risk for cardiovascular disease in women with increased psychological stress due to shift work.30

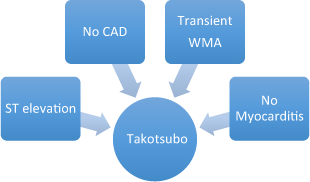

Other syndromes such as Takotsubo’s “broken heart syndrome” provide a clear link between stress in women and heart disease.31 In this model, extreme emotional or physical stress in women results in apical ballooning of the heart and can mimic an acute myocardial infarction. It is clear that in women there is a direct link between stress and cardiovascular abnormalities. It is postulated that the emotional or physical stress results in an activation of the neurohormonal axis and causes a surge in catecholamines. The high levels of catecholamines have been thought to induce coronary vasospasm, microvascular vasospasm and even cellular injury to cardiac myocytes.32,33 Luckily with Takotsubo’s syndrome, the damage is reversible and most patients are able to return to normal life with a normal heart as long as they are able to control their response to stress adequately.

Figure 9.2 Diagnostic features of Takotsubo’s “ stress-induced” cardiomyopathy. WMA = wall motion abnormality.

Emotional and psychological stressors have been proven to increase risk for heart disease and worsen outcomes in women.34 In addition, men and women respond differently to different types of psychosocial stressors — for example, men who are married have lowered risk for heart disease but in women, marriage increases risk.35

Stress reduction is a key component to improving heart disease in women. In the SWITCHD trial, interventions to reduce stress in women were evaluated and researchers found that a group-based stress reduction program resulted in a lower risk of death in women with heart disease.36 As compared to those women in the standard treatment group, those that participated in a psychosocial intervention designed to reduce stress were found to have a seven-year mortality rate of 7% (as compared to 30% in the standard therapy group). It is clear that stress reduction is an important part of prevention of heart disease. In women, the effects of different types of stressors may be different than those of men — we must continue to individualize treatment in order to maximize outcomes.

What are effective stress reduction techniques for women?

There are numerous publications and techniques for stress reduction available. The key is to determine what works best for each individual and what each person can incorporate into their daily routines. More common stress reduction tips include:

1.Meditate: Meditation can be a critical component for stress reduction. It allows you to be alone with your thoughts and focus on nothing but your own body. Meditation can be helpful in lowering heart rate and blood pressure and can be learned quickly. Some experts argue that daily five-minute meditation sessions can be quite successful.

2.Breathe deeply: Deep breathing or relaxation breathing can be used on its on or as a part of meditation. It can be incredibly effective in lowering both blood pressure and heart rate. Often, when we feel overwhelmed by stress, a moment of breathing exercises can significantly improve the way our bodies respond to stress.

3.Socialize/Social support: Having someone to talk to about life’s stresses is another effective way to handle stress better. By verbalizing our feelings and sharing common experiences with others, patients are often better able to handle challenges and ultimately improve their coping mechanisms.

4.Exercise: Exercise is critical to cardiac health. Obviously, exercise helps reduce obesity and improves cardiovascular fitness. In addition, exercise can also help patients to manage stress better. Exercise is a great way to relax and spend time “alone with your thoughts”.

5.Organize and plan: Much of what contributes to stress is the fear of the unknown and uncertainty in the lives of our patients. By organizing and creating a family plan, many of the stressors can be relieved. Specifically, creating a family budget can help reduce the stress associated with financial pressures and obligations.

6.Eat healthily: Healthy eating can make an enormous difference in the way in which we all feel. Healthy nutritional choices can actually affect mood. Excessive junk food consumption has been associated with depression and anxiety.

Figure 9.3 Strategies for stress reduction.

Ultimately, we must empower women to take control of their own cardiovascular health through education and increasing awareness of risk. Obesity and stress can play an important role in the development and exacerbation of cardiovascular disease. By modifying diet and working to manage stress more effectively, women can make a significant difference in their own risk profiles for heart disease. As healthcare professionals we must provide support and counseling as our female patients set goals and develop plans for change.

1 Anderson, T., Backer, O. G., Stockholm, K. H. et al. (1984). Randomized trial of diet and gastroplasty with diet alone in morbid obesity. N Engl J Med, Volume 310, 352–356.

2 Brownell, K. D. and Jeffrey, R. W. (1987). Improving long-term weight loss: pushing the limits of treatment. Behav Ther, Volume 18, 353–374.

3 Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C. et al. (2001). Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr, November, Volume 74(5), 579–584.

4 McGuire, M. T., Wing, R. R., Klem, M. L. et al. (1999). What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol, Volume 67, 177–185.

5 Wing, R. R. and Phelan, S. (2005). Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr, July, 82(1), 222S–225S.

6 Gorin, A., Phelan, S., Hill, J. A. et al. (2004). Medical triggers are associated with better long-term weight maintenance. Prev Med, Volume 39, 612–616.

7 Krauss, R. M., Eckel, R. H., Howard, B. et al. (2000). AHA dietary guidelines, revision 2000: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation, Volume 102, 2296–2311.

8 Atkins, R. C. (1998). Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution. New York: Avon Books.

9 Bravata, D. M., Sander, L., Huang, J. et al. (2003). Efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets: a systematic review. JAMA, Volume 289, 1837–1850.

10 Jenkins, D. J. A., Thomas, D. M., Wolever, S. et al. (1981). Glycemic index of food: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr, Volume 34, 362–366.

11 Lefebvre, P. J. and Scheen, A. J. (1998). The postprandial state and risk of cardiovasular disease. Diabet Med, Volume 15, S63–S68.

12 Lichtenstein, A. H. and Van Horn, L. (1998). AHA science advisory: very low fat diets. Circulation, Volume 98, 935–939.

13 Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A. and Sanchez-Villegas, A. (2004). The emerging role of Mediterranean diets in cardiovascular epidemiology: monounsaturated fats, olive oil, red wine or the whole pattern? Eur J Epidemiol, Volume 19, 9–13.

14 Mendez, M. A., Popkin, B. M. and Jakszyn, P. (2006). Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced 3-year incidence of obesity. J Nutr, Volume 136, 2934–2938.

15 Trichopoulou, A., Orfanos, P., Norat, T. et al. (2005). Modified Mediterranean diet and survival: EPIC-elderly prospective cohort study. BMJ, Volume 330, 991.

16 Trichopoulou, A., Bamia, C. and Trichopoulos, D. (2005). Mediterranean diet and survival among patients with coronary heart disease in Greece. Arch Intern Med, Volume 165, 929–935.

17 Willett, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E. et al. (1993). Intake of trans fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among women. Lancet, Volume 341, 581–585.

18 FDA (2013). Tentative determination regarding partially hydrogenated oils. Federal Register, Volume 78(217), 67169–67175.

19 Hu, F. B., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E. et al. (1997). Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. NEJM, Volume 337, 1491–1499.

20 Hu, F. B., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E. et al. (1998). Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ, Volume 317, 1341.

21 Fraser, G. E., Sabate, J., Beeson, W. L. et al. (1992). A possible protective effect of nut consumption on risk of coronary heart disease. The Adventist Health Study. Arch Intern Med, Volume 152, 1416–1424.

22 Marcouxa, B. C., Trenknerb, L. L. and Rosenstockc, I. M. (1990). Social networks and social support in weight loss. Patient Education and Counseling, Volume 15, 229–238.

23 Harvey-Berino, J., Pintauro, S., Buzzell, P. et al. (2004). Effect of internet support on the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Obesity Research, Volume 12(2), 320–329.

24 McEwen, B. (1998). Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med, Volume 338, 171–179.

25 Segerstrom, S. and Miller, G. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull, Volume 130(4), 601–630.

26 Chan, S. R. and Blackburn, E. H. (2004). Telomeres and telomerase. Philos Trans R Soc London B, Volume 359(1441), 109–121.

27 Irie, M., Asami, S., Ikeda, M. et al. (2003). Depressive state relates to female oxidative DNA damage via neutrophil activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, Volume 311, 1014–1018.

28 Epel, E. S., Blackburn, E. H., Lin, J., et al. (2004). Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. PNAS, Volume 101(49), 17312–17315.

29 Coffey, L. C., Skipper, J. K. and Jung, F. D. (1998). Nurses and shift work: effects on job performance and job-related stress. J Adv Nursing, Volume 13, 245–254.

30 Kawachi, I. (1995). Prospective study of shift work and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation, Volume 92, 3178–3182.

31 Gianni, M., Dentali, F., Grandi A. M. et al. (2006). Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J, Volume 27(13), 1523–1529.

32 Kurisu, S., Inoue, I., Kawagoe, T. et al. (2004). Time course of electrocardiographic changes in patients with tako-tsubo syndrome: comparison with acute myocardial infarction with minimal enzymatic release. Circ J, Volume 68, 77–81.

33 Abe, Y., Kondo, M., Matsuoka, R. et al. (2003). Assessment of clinical features in transient left ventricular apical ballooning. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 41, 737–742.

34 Dimsdale, J. E. (2008). Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 51, 1237–1246.

35 Nealey-Moore, J. B., Smith, T. W., Uchino, B. N. et al. (2007). Cardiovascular reactivity during positive and negative marital interactions. J Behav Med, Volume 30, 505–519.

36 Orth-Gomér, K. (2009). Stress reduction prolongs life in women with coronary disease,The Stockholm Women’s Intervention Trial for Coronary Heart Disease (SWITCHD). Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, Volume 2, 25–32.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree