Syncope and Sudden Death

“The coroner’s jury sat upon the corpse, and, like sensible men, returned an unassailable verdict of ‘sudden death.’”

–Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables

Syncope in Children and Adolescents

Does syncope identify a subset of patients at increased risk for sudden death? Certainly, some of the conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, prolonged QT-interval syndrome, Brugada syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension are known to be associated with both syncope and sudden death. However, this does not mean that syncope, in a general population, is a precursor or predictor of sudden death.

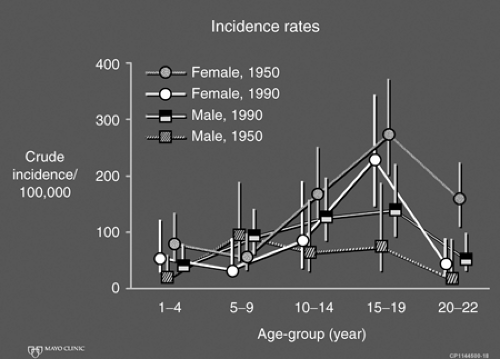

Approximately 15% of adolescents faint at least once. We reported that syncope occurred in 90 to 166 of 100,000 females and in 48 to 93 of 100,000 males aged between 1 and 22 years, depending on the period when the patients were studied (see Fig. 7-1). Also, in this study, the long-term survival of children and adolescents was not different from that of an age-matched population. However, one patient had prolonged QT-interval syndrome and another died suddenly and unexpectedly. Both these patients had had syncope during exercise. Syncope during exercise may be a clue to identify patients who may have a serious underlying cause for syncope.

McHarg et al. studied 108 children ages 2 to 19 years who were referred to a pediatric neurologist or cardiologist for evaluation of syncope. They found that 75% of the patients had vasovagal syncope, 11% had migraine, 8% had seizures, and 6% had cardiac arrhythmias. Of the six patients with cardiac arrhythmias, two had long QT-interval syndrome, one had atrial flutter, two had ventricular tachycardia (one with associated endocardial fibroelastosis), and one had WPW syndrome. Only one patient, who had ventricular tachycardia, died. This was not a population-based study and had inherent ascertainment bias.

Although syncope is very common in children and adolescents, it does not appear that syncope in otherwise healthy children is a predictor of sudden death, except if the syncope occurs during exercise. What then is the appropriate evaluation for an otherwise healthy child or adolescent who faints? What is the role of echocardiography, electrocardiography, or tilt table testing?

Figure 7.1 • Occurrence rates of syncope in males and females. Syncope is more common in girls than in boys. |

Most episodes of syncope in adolescents likely result from a “normal” autonomic imbalance that occurs in this age-group (“autonomic imbalance of adolescence”) and is more common in girls than in boys. This results in a less well-tuned adjustment of heart rate and blood pressure to a number of situations such as postural changes, emotional stresses, relative hypovolemia, and certain tactile stimuli (e.g., having one’s hair brushed or pulled). These episodes are what McHarg labeled vasovagal but now frequently are termed vasodepressor or cardio inhibitory syncope. Although one probably can classify these episodes further on the basis of the response to tilt table testing, the clinical usefulness of this testing remains to be proved.

When obtaining a history of syncope, it is important to be sure that the patient really had syncope and did not just have posture-related dizziness. Patients and their families frequently use the term passed out or blacked out although the patient did not lose consciousness.

It is important to determine whether the syncope occurred during or immediately after exercise. It is also important to know whether there is a family history of premature sudden death, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, drowning, and/or automobile accident–related deaths. It may be helpful to know whether the patient was injured as a result of the syncopal episode. In general, patients are not injured during a vasovagal episode but are more likely to be injured if the episode occurred because of an important underlying cardiac or neurologic problem. Patients are more likely to recall that they felt unwell and were about to faint before a vasovagal faint, whereas they are less likely to recall this if there was an important underlying cause of the event.

If the syncopal event had all the hallmarks of a vasovagal episode, the physical examination is completely normal (including a thorough cardiac and neurologic examination), and there is no family history of sudden death, then there is little data to suggest that additional testing is necessary. Some, however, would consider it prudent to do an electrocardiogram (ECG).

If the syncopal event was not typical of a vasovagal episode or occurred during or immediately after exercise, or there was a positive family history (see preceding text), then further testing is indicated. The specific tests would depend on the specific situation and might include (but not limited to) an ECG, echocardiogram, 24-hour ECG monitoring, exercise testing, blood glucose measurement, and appropriate neurologic testing.

Treatment, of course, depends on the underlying cause. However, one should not overtreat patients who have classical vasovagal presyncope. These patients are best treated with an explanation of the cause of the syncopal episode and with increased fluid intake and liberalized dietary salt. It is unclear if β-blockers, mineralocorticoids, or α-agonists are more effective than fluid and salt liberalization in preventing additional syncopal events in children.

Sudden Death in Children and Adolescents

One can categorize sudden death in children and adolescents as sudden infant death syndrome, sudden death in patients with known heart disease, or sudden death in presumably healthy children and adolescents exclusive of sudden infant death syndrome. This discussion is limited to sudden death in presumably healthy children older than 1 year and adolescents (i.e., exclusive of sudden infant death syndrome).

Sudden unexpected death in presumably healthy children and adolescents, as compared to that in adults, is relatively uncommon. We studied subjects in Olmsted County, Minnesota, ranging from 1 to 22 years of age. Sudden unexpected death occurred in 12 subjects (2.3%). This represented an incidence of 1.3 per 100,000 patient years. Kennedy et al. studied subjects in St. Louis County, Missouri, and reported the incidence of sudden unexpected death in children aged 1 to 9 years to be 2.5 and 8.5 per 100,000 patient years during 1981 and 1982 respectively. For subjects aged 10 to 19 years, the incidences were 2.4 and 5.3 for 1981 and 1982 respectively. Investigators (Neuspiel and Kuller) studying sudden deaths in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, reported 207 cases of sudden unexpected death among a total of 948 nontraumatic deaths in individuals aged between 1 and 21 years, with an incidence of 4.6 per 100,000 patient years. The difference in the incidence rates between these studies may be accounted for by the different demographics of the populations studied and by differences in the interpretation of the definition of sudden unexpected death. In the first study, deaths from infectious disease identified before death, which can be associated with death (e.g., meningitis, epiglottitis), were not included, whereas these were included in the last study. Hence, the “real” incidence of sudden unexpected death in this age-group is somewhere between 1.3 and 4.6 per 100,000 patient years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree