31 Syncope

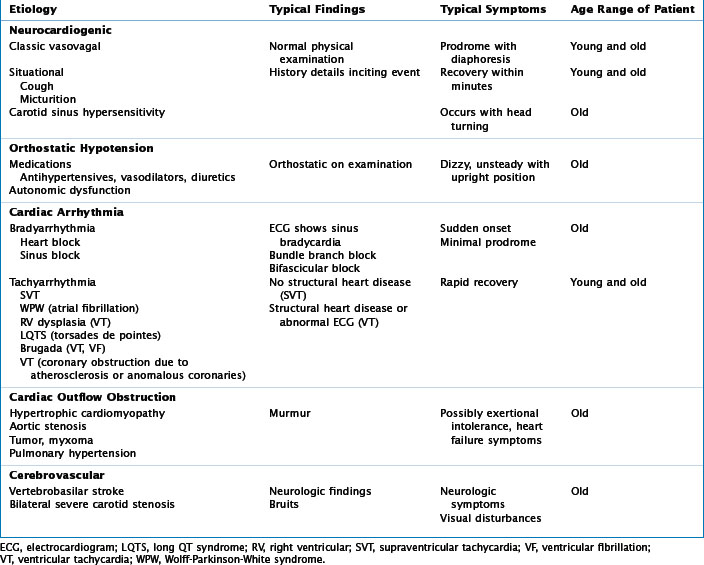

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness with an inability to maintain postural tone. Typically, it is quickly followed by a spontaneous recovery of consciousness and the ability to resume the initial upright position. Syncope does not include other conditions of altered consciousness such as seizure or shock, but can be difficult to distinguish from them. Syncope is very common and is responsible for 1% to 5% of visits to emergency departments and approximately 5% of hospital admissions. This translates into almost a million syncope evaluations in the United States each year. The various etiologies of syncope can be divided into five broad categories including neurally mediated (i.e., vasovagal), orthostatic (most common), cardiac arrhythmia (both tachycardia and bradycardia), cardiac lesions obstructing outflow (i.e., aortic stenosis), and cerebrovascular ischemic attacks such as a vertebrobasilar attack (which is a rare cause of syncope) (Table 31-1). The dilemma is to differentiate benign neurally mediated syncope (NMS) from less common but more harmful etiologies.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Neurally Mediated Syncope

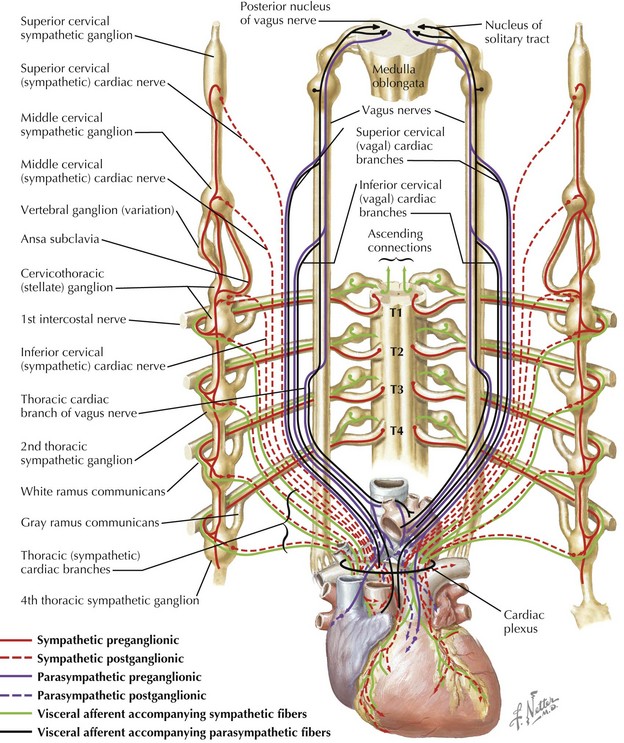

NMS, also referred to as “vasovagal syncope,” is the most common cause of syncope. Typical fainting is not a pathologic cardiac condition, but most likely a remnant defense mechanism in response to stress that dates back to the origins of humans and is also seen in other vertebrate animals in response to stress. Several types of situational syncope are also neurally mediated, such as micturition, postprandial, and post-exercise syncope. The pathophysiology of NMS remains to be fully elucidated. Several theories involve baroreceptor reflex abnormalities that cause disconnection between the autonomic nervous system and the cardiovascular system. Another theory is that venous pooling that occurs with the upright position leads to reduced cardiac filling, which then leads to activating mechanoreceptors that cause a paradoxical withdrawal of sympathetic tone (Fig. 31-1). The triad of apnea, bradycardia, and hypotension was first termed the Bezold-Jarisch reflex in the 1940s when it was appreciated that afferent and efferent pathways in the vagus nerve control heart rate and vasomotor tone by increasing or decreasing parasympathetic discharge to the heart. Several cardiac receptors are part of the intricate network including various baroreceptors and chemoreceptors.

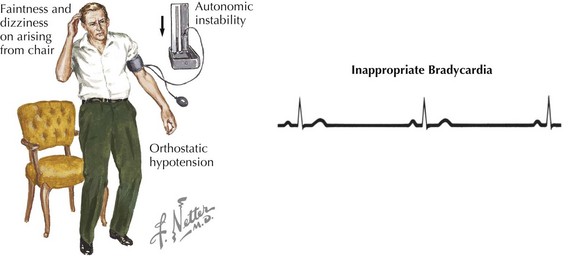

Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension is a common cause of syncope, particularly in elderly individuals or in individuals with decreased intravascular volume status from any of a number of causes. The American Autonomic Society defines orthostatic hypotension as a drop of at least 20 mm Hg of systolic pressure or at least 10 mm Hg of diastolic pressure within 3 minutes of standing. Some primary disorders of the autonomic nervous system cause orthostatic hypotension such as Parkinson’s disease and Shy-Drager syndrome, and some disorders secondarily affect the autonomic system such as diabetes mellitus or a paraneoplastic process (Fig. 31-2). Also, many medications cause or exacerbate orthostatic hypotension, which disproportionately affect the elderly and are a frequent cause of falls and syncope.

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms that surround a syncopal event can often aid in determining the underlying etiology (Box 31-1).The quality and duration of symptoms preceding the loss of consciousness can vary considerably depending on the etiology. Observations of witnesses are also very important and can help recreate the events and timeline from prodrome to duration of unconsciousness and mental status upon arousal. Typically, NMS patients have a prodrome before losing consciousness that lasts from several seconds to minutes. The prodrome may consist of nausea, diaphoresis, anxiety, or palpitations. These symptoms are followed by a very brief period of unconsciousness (usually less than 1 minute) and then a rapid recovery within a few minutes. After the event, the patient may feel fatigued but should be oriented and coherent. These episodes generally occur when the person is in the upright position, similar to orthostatic hypotension events. Occasionally, patients will have little or no warning before passing out. A lack of prodrome is more frequently associated with an arrhythmic etiology. Traditionally, Stokes-Adams syndrome has been used to describe this abrupt loss of consciousness due to a marked decrease in heart rate, although it has come to represent abrupt loss of consciousness from both tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias. If syncope occurs during exertion it is imperative that cardiac etiologies be considered. Chest pain may also accompany a tachycardic arrhythmia such as VT due to coronary disease.

Box 31-1 Key Questions for the Patient with a History of Syncope