Mariell Jessup, Michael A. Acker

Surgical Management of Heart Failure

In the current era of management of heart failure associated with a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), clinicians frequently encounter optimally treated patients who remain symptomatic. Indeed, despite the variety of available medical therapies and electrophysiologic interventions, such as placement of biventricular pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (see Chapter 26), many patients who have been so treated are still left with a reduced quality of life and a poor prognosis. In a subpopulation of these patients, surgical intervention may be appropriate to alleviate ischemia, to attenuate valvular dysfunction, to reduce mechanical disadvantages caused by ventricular remodeling, or, when all other treatment options have failed, to perform cardiac transplantation or implantation of a permanent ventricular assist device (VAD) (see Chapter 29).1 This chapter describes the surgical management of patients with heart failure secondary to a low ejection fraction. The medical management of patients with a reduced ejection fraction is discussed in Chapter 25, and the role of circulatory assist devices is discussed in Chapter 29.

Coronary Artery Revascularization

Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Selection of Patients for Coronary Artery Revascularization

Until the design, completion, and publication of the STICH (Surgical Treatment of Ischemic Heart Failure) trial,2 no randomized clinical trials had evaluated the outcomes of revascularization in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. The three major randomized clinical trials that have compared coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with medical management—the Veterans Administration Cooperative Study, the European Coronary Surgery Study, and the Coronary Artery Surgery Study—all had excluded patients with heart failure or severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. Several clinical factors have traditionally played a major role in the decision-making process with respect to selection of suitable candidate patients with heart failure to undergo coronary artery revascularization, including the presence of angina, severity of heart failure symptoms, LV dimensions, degree of hemodynamic compromise, and presence and severity of comorbid conditions. Other major technical issues to be considered are the adequacy of target vessels for revascularization and an adequate conduit strategy. The most important determinant remains the extent of jeopardized but still viable myocardium (see Chapters 14, 16, and 17). Studies have suggested that for a significant reduction in heart failure symptoms and improvement in LV function, as well as in survival after coronary revascularization, at least 25% of the myocardium should be viable. Of interest, in the STICH trial (see further on), the presence of viable myocardium was associated with a greater likelihood of survival in patients with coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction, irrespective of treatment. The assessment of myocardial viability, however, did not identify patients with a differential survival benefit with CABG as versus medical therapy alone. The role of viability testing in the decision-making process is still evolving after the publication of this STICH trial substudy.3

Risks of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

The perioperative risks in patients with severe LV dysfunction range from 2% to nearly 10%, depending on the availability of targets and their viability, right ventricular dysfunction, advanced heart failure symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class IV), increased LV end-diastolic pressure, comorbidities of advanced age, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.4,5 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)–predicted risk of death in 2006 for a 70-year-old patient with no comorbid conditions but with a 20% LVEF was 1.6%; for a man of the same age with a normal LVEF, this risk was 0.9%. Mortality rates increase substantially when the LVEF is below 20% or when heart failure is severe (NYHA class IV).

Studies have indicated that for patients with clinical heart failure, perioperative mortality rates range from approximately 2.6% to 8.7%, depending on age and presence of one or more comorbid conditions. Pocar and associates5 found a 30-day mortality rate of 4.4% in 45 consecutive angina-free patients with NYHA class III or IV, LVEF below 35%, and significant viability by positron emission tomography (PET). Predictors of death included LV end-diastolic pressure above 25 mm Hg, age older than 70 years, and significant peripheral vascular disease. In the CABG Patch trial, patients without angina or heart failure had a perioperative mortality of 1.3%. The mortality increased to 4.8% for patients with no angina and mild heart failure, NYHA class I or II, and 7.4% with no angina and NYHA class III or IV heart failure.5 For cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction, the results of emergent CABG are poor but still better than medical therapy. The SHOCK (Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock) trial gave 30-day and 6-month mortality rates after CABG of 47% and 50%, respectively, for patients in cardiogenic shock. These rates were 56% and 63% with medical therapy alone.6

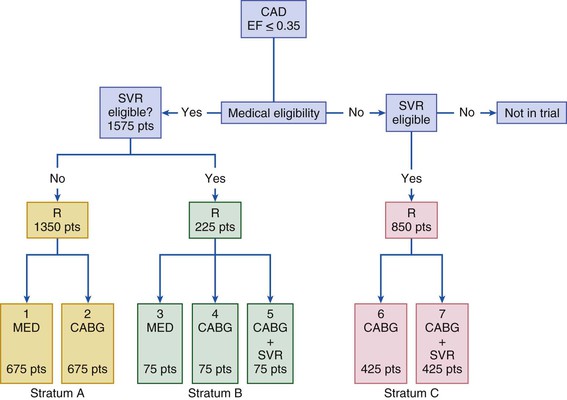

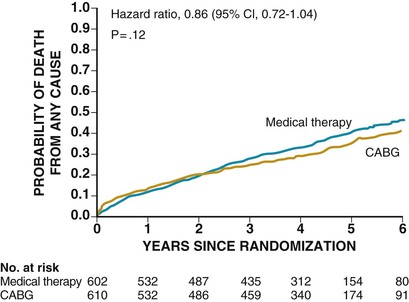

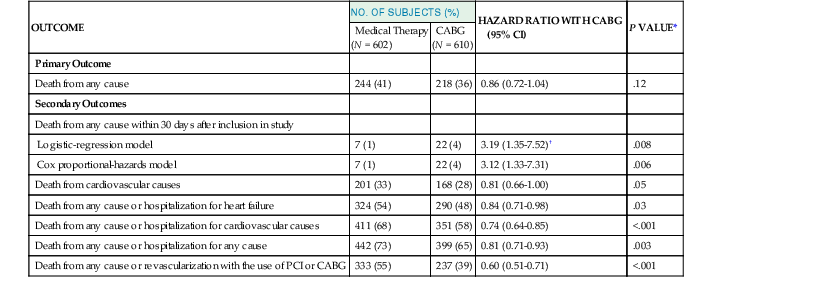

The STICH trial was a prospective, randomized, intention-to-treat study of 2800 patients from 100 centers.2 Patients on an optimal medical regimen with LV dysfunction and coronary artery disease amenable to CABG were randomly assigned to one of three different treatment strategies: CABG, CABG plus surgical ventricular reconstruction (SVR), or medical therapy alone (MED) (Fig. 28-1). This trial was powered to address two primary hypotheses: (1) CABG combined with medical therapy improves long-term survival over that achieved with MED; and (2) SVR provides additional long-term survival benefit when it is combined with CABG and medical therapy. Between July 2002 and May 2007, a total of 1212 patients with an LVEF of 35% or less and coronary artery disease amenable to CABG were randomly assigned to receive medical therapy alone (602 patients) or medical therapy plus CABG (610 patients). The primary outcome was the rate of death from any cause. Major secondary outcomes included the rates of death from cardiovascular causes and of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes. Of the 610 patients randomly assigned to CABG, 555 (91%) underwent CABG before the end of the study. A concurrent mitral valve operation was performed in 63 patients (11%). The all-cause death rate within 30 days of assignment to treatment, which is a rough estimation of perioperative mortality, was 4% in the medical treatment plus CABG arm, compared with 1% 30-day mortality rate in the medical treatment group (Fig. 28-2).

Benefits of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

The beneficial effect of revascularization should, theoretically, result from improved blood flow to hypoperfused but viable myocardium, with a subsequent improvement in LV function and clinical outcomes. Alleviation of ischemia also may lessen the tendency toward proarrhythmias, thereby reducing the incidence of sudden cardiac death. Accordingly, coronary artery revascularization has the potential to relieve symptoms of heart failure, improve LV function, and enhance survival.

In the STICH trial, the intention-to-treat analysis (see Fig. 28-2) found no statistically significant difference in death from any cause between the medical (MED) and the surgical groups (hazard ratio [HR] for CABG, 0.86; 95% CI, 90.7 to 1.04; P = .12]), whereas the prespecified secondary analysis (Table 28-1) found a significant difference between the medical and surgical groups with respect to the combined endpoints of cardiovascular death, death from any cause, and hospitalization for cardiovascular causes (HR for CABG, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.64 to 0.85]; P < .001). The HR for cardiovascular death was 19% lower in the CABG arm (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.00) and for the composite of death or cardiovascular hospitalization was 16% lower in the CABG arm (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.98). These findings were consistent across several prespecified subgroups. Although the STICH trial showed no significant difference between medical therapy alone and medical therapy plus CABG with respect to all-cause death, 17% of the patients in the MED group crossed over from that arm of the study to undergo CABG. Of note, patients in the surgical (CABG) group had lower rates of death from cardiovascular causes and death from any cause or rates of hospitalization for cardiovascular causes, when compared with those patients assigned to medical therapy alone. Subsequently, Velasquez and colleagues prospectively applied the STICH trial entry criteria to an observational database to determine whether CABG decreases mortality compared with MED for patients with coronary artery disease and depressed LVEF.7 In their analysis, 763 patients were included for propensity score analysis, including 624 who received MED and 139 who underwent CABG. Adjusted mortality curves were constructed for those patients in the three quintiles most likely to receive CABG. The curves diverged early, with risk-adjusted mortality rates at 5 years of 46% for MED and 29% for CABG, and the survival benefit of CABG over MED continued through 10 years of follow-up (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.88). The investigators concluded that in a propensity-matched, risk-adjusted observational cohort of patients with coronary artery disease, LVEF less than 35%, and no left main artery stenosis greater than 50%, CABG is associated with a survival advantage over MED through 10 years of follow-up.

TABLE 28-1

The STICH Study Outcomes

| OUTCOME | NO. OF SUBJECTS (%) | HAZARD RATIO WITH CABG (95% CI) | P VALUE* | |

| Medical Therapy (N = 602) | CABG (N = 610) | |||

| Primary Outcome | ||||

| Death from any cause | 244 (41) | 218 (36) | 0.86 (0.72-1.04) | .12 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

| Death from any cause within 30 days after inclusion in study | ||||

| Logistic-regression model | 7 (1) | 22 (4) | 3.19 (1.35-7.52)† | .008 |

| Cox proportional-hazards model | 7 (1) | 22 (4) | 3.12 (1.33-7.31) | .006 |

| Death from cardiovascular causes | 201 (33) | 168 (28) | 0.81 (0.66-1.00) | .05 |

| Death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure | 324 (54) | 290 (48) | 0.84 (0.71-0.98) | .03 |

| Death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes | 411 (68) | 351 (58) | 0.74 (0.64-0.85) | <.001 |

| Death from any cause or hospitalization for any cause | 442 (73) | 399 (65) | 0.81 (0.71-0.93) | .003 |

| Death from any cause or revascularization with the use of PCI or CABG | 333 (55) | 237 (39) | 0.60 (0.51-0.71) | <.001 |

* All P values were calculated with the use of the log rank test, except for one of the analyses of death from any cause within 30 days after randomization, for which, as noted, the P value was calculated with the use of the logistic regression model.

† This value is an odds ratio rather than a hazard ratio.

PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

From Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al: Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 364:1607, 2011.

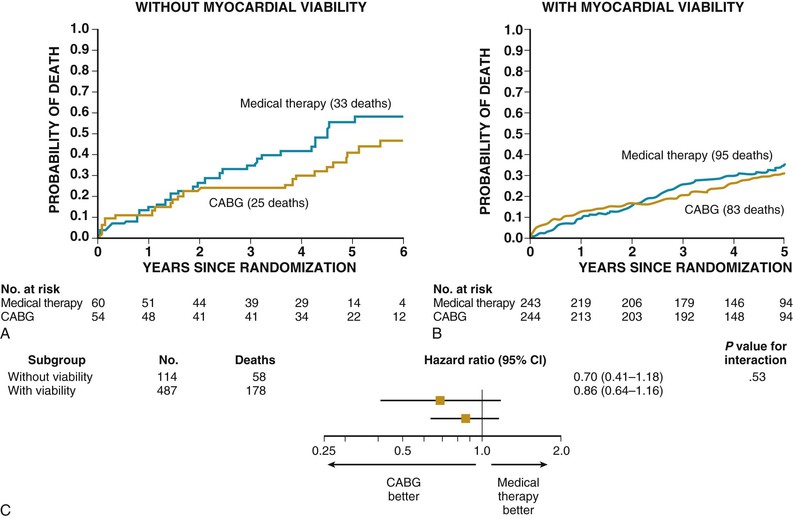

Improvement in Left Ventricular Function

Before publication of the STICH viability study, a review of pooled viability data demonstrated that significant viability (25% to 30%) predicted an improvement in LVEF. Nuclear studies, PET, and dobutamine echocardiography predict improvement of LV function of approximately 8% to 10% after CABG when viability of the myocardium is present. Similarly, PET, nuclear studies, or dobutamine echocardiography images that demonstrate the absence of viability are likewise useful to predict the absence of improvement in LVEF after surgery.8,9 In the STICH trial, among the 1212 patients enrolled in the randomized trial, 601 underwent assessment of myocardial viability.3 Of these patients, 298 patients were randomly assigned to receive medical therapy plus CABG and 303 to receive medical therapy alone. A total of 178 of 487 patients with viable myocardium (37%) and 58 of 114 patients without viable myocardium (51%) died (HR for death among patients with viable myocardium, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.86; P = .003). The presence of viable myocardium was associated with a greater likelihood of survival in patients with coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction, but this relationship was not significant after adjustment for other baseline variables. In addition, as mentioned earlier, no significant interaction was found between viability status and treatment assignment with respect to mortality (P = .53), depicted in Figure 28-3. Although the precise reasons for the discrepancy between results of the STICH viability study and previous studies that showed the importance of viability in predicting CABG outcomes is not known, it may relate to the more aggressive use of medical therapy in the STICH trial, which resulted in a decrease in annual mortality when compared with the mortality rates that were published in prior viability analyses. The impact of CABG on LVEF in the STICH trial has not been published.

Symptomatic Improvement

Several studies have reported marked reduction in heart failure symptoms after revascularization. In 1999, a study from Verona10 followed 167 patients, with an average LVEF of 28%, with angina and heart failure symptoms, and demonstrated significant freedom from angina after surgery, 98% and 81% at 1 and 5 years. Rates of freedom from heart failure were 78% and 47% at 1 and 5 years, respectively. Only 54% of patients were symptom-free of both angina and heart failure at follow-up evaluation. Di Carli and colleagues studied 36 patients with LVEF of 28% by PET imaging.11 They found a significant correlation between the total extent of a PET blood flow–metabolism mismatch and percentage improvement in functional class after CABG. A mismatch of more than 18% was associated with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 78% for predicting a change in functional status after revascularization. A substantial objective improvement in physical activity was noted in patients with presurgical mismatches that occupied at least 20% of the ventricular myocardium. Thus patients with large perfusion-metabolism mismatch exhibited the greatest clinical benefit after revascularization. The impact of the CABG strategy on subsequent symptoms of patients in the STICH trial has not been published.

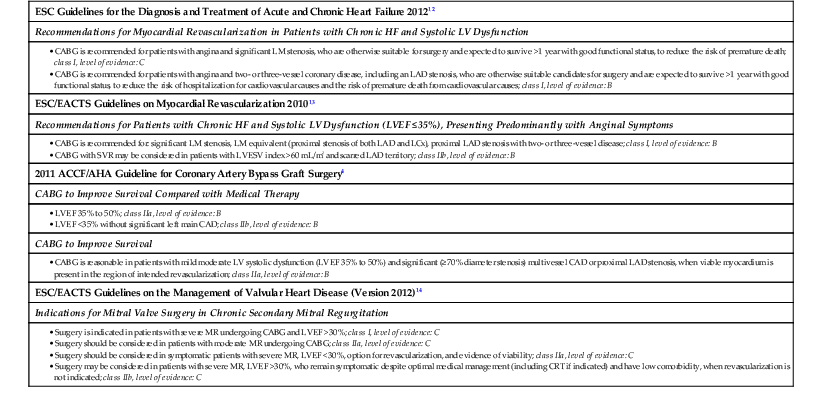

A reasonable management strategy for patients who present with heart failure secondary to coronary artery disease (i.e., ischemic cardiomyopathy) includes coronary angiography (see Chapter 20), especially if patients have any component of angina pectoris. Viability studies may be appropriate for those patients with severe disease and adequate surgical targets. If significant viability (≥25%) is documented, the weight of currently available clinical evidence suggests that CABG may be superior to medical therapy alone in outcome measures of survival and quality of life.9 Current American and European guidelines for CABG in patients with heart failure and low LVEF embody various strengths of recommendation for surgery, as shown in Table 28-2.12–14

TABLE 28-2

Surgery for Management of Heart Failure (HF): Guideline Recommendations

| ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 201212 |

| Recommendations for Myocardial Revascularization in Patients with Chronic HF and Systolic LV Dysfunction |

| ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Myocardial Revascularization 201013 |

| Recommendations for Patients with Chronic HF and Systolic LV Dysfunction (LVEF ≤35%), Presenting Predominantly with Anginal Symptoms |

| 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery4 |

| CABG to Improve Survival Compared with Medical Therapy |

| CABG to Improve Survival |

| ESC/EACTS Guidelines on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease (Version 2012)14 |

| Indications for Mitral Valve Surgery in Chronic Secondary Mitral Regurgitation |

CAD = coronary artery disease; CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy; ESC/EACTS = European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx = left circumflex coronary artery; LM = left main coronary artery; LVESV = left ventricular end-systolic volume.

Modified from McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al: ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 33:1787, 2012.

Valve Surgery in Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction

Mitral Valve

As discussed in Chapter 63, the surgical treatment of primary valvular heart disease that leads to LV dysfunction or heart failure is now widely accepted. However, patients who have valvular dysfunction secondary to, or in association with, a primary cardiomyopathy pose a much more difficult management problem. The following discussion focuses on the impact and outcome of valve repair or replacement for patients with a dilated cardiomyopathy and secondary mitral regurgitation (MR).15 However, much of the same controversy relates to the decision to repair or replace the regurgitant mitral valve in the patient with an ischemic cardiomyopathy and a low LVEF who is undergoing CABG.

MR is commonly observed in patients with heart failure and is associated with a poor prognosis. Progressive LV remodeling, characterized by increasing LV dilation with change to a more spherical shape, can result in functional MR secondary to annular dilation, papillary muscle displacement, and chordal tethering. The functional MR leads to an increased preload, increased wall tension, and increased LV workload, all of which contribute in a positive feedback loop to progressive heart failure. The presence of MR itself is an independent risk factor for poor outcome, in both nonischemic and ischemic forms of the disorder. Even uncorrected mild MR, as well as moderate to severe MR associated with ischemic cardiomyopathy, is associated with reduced long-term survival. In addition, MR is a progressive disorder in which the regurgitation-related LV volume overload promotes further LV remodeling, leading to worsening of the problem.

Mitral valve repair or replacement to restore valve competency is a well-established procedure when symptoms of heart failure are present and the primary disease is of the valve leaflets (see Chapter 63). More specifically, however, interest has focused on functional or secondary mitral insufficiency, in which the valve leaflets are anatomically normal but do not fully coapt because of annular dilation and restricted leaflet motion secondary to increased ventricular size and sphericity. Such remodeling of the ventricle often is associated with an LVEF of 40% or less and heart failure symptoms of NYHA class III or class IV. Surgery in this situation is controversial, because the MR is the consequence and not the cause of LV dysfunction, and the prognosis is therefore more specifically related to the underlying cardiomyopathic process.

Although it is clear that the advent of secondary mitral insufficiency is associated with a worse prognosis, it is unclear whether the worse outcomes stem from the MR itself or whether MR is simply a marker for worsening heart failure and the correction of MR will improve symptoms or survival. Specifically, can surgery be done in patients with advanced heart failure and LV dysfunction with an acceptable operative mortality? Does the available evidence show that the elimination of MR results in LV reverse remodeling or improved survival? Conventional teaching has been that surgical correction of MR in patients with advanced heart failure patients with poor LV function is associated with prohibitive operative mortality. This view was challenged by Bolling in the mid-1990s, ushering in the era of both mitral valve repair and other surgical procedures for the failing heart.16 The traditional hypothesis held that the mitral valve functions as a “pop-off” mechanism for the failing ventricle and that surgical correction results in prohibitive mortality. The Bolling hypothesis is that there is an “annular solution for a ventricular problem . . . such that reconstruction of the mitral valve annulus’ geometric abnormality by an undersized ring restores valvular competency, alleviates excessive ventricular workload, improves ventricular geometry and improves ventricular function.”17 Miller and his Stanford colleagues reported that in an ischemic sheep model of MR, reduction of the annulus by a small ring reduces a radius of curvature of the left ventricle at the base equatorial and apical levels.18 This finding supports the concept that a small ring can restore a more elliptical ventricular shape. It is now recognized that the surgical mortality for mitral valve replacement observed in the past probably was the result of the loss of the subvalvular apparatus and not secondary to the loss of the pop-off valve as previously thought, underscoring the paramount importance of maintaining annular and subvalvular continuity during mitral valve surgery. Bolling was the first to show an acceptable operative mortality (5%) in a series of 140 NYHA class III and class IV patients with an LVEF of less than 25% and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. He demonstrated improvement in LVEF and a decrease in end-diastolic volumes during 3 to 5 years, as well as improvement in functional class.

A more comprehensive analysis of correction of MR in advanced heart failure patients with nonischemic LV dysfunction comes from Acker and colleagues in the Acorn trial.19 This trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of mitral valve surgery with and without the CorCap cardiac support device. The Acorn clinical trial, although not randomized to study the efficacy of mitral valve repair, did prospectively assess the safety and efficacy of mitral valve surgery in patients with advanced heart failure in multiple trial centers. Of 193 subjects entered, 73% were in class III. Most of the patients had idiopathic or valvular disease; only 6% had ischemic cardiomyopathy. The mean duration of heart failure approached 5 years; 97% of patients were taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and 80% were taking beta blockers. The mean LVEF was 23.9%, peak  was 14 mL/kg/min, and LV end-diastolic dimension was nearly 70 mm. The operative mortality rate was only 1.6%—especially noteworthy because it represents the outcomes for nearly 30 different centers. Twelve-month cumulative survival was 86.5%; at 2 years, the cumulative survival was 85.2%. A majority of patients underwent a complete, small annuloplasty repair. Mitral valve insufficiency was reduced from 2.7 at baseline to 0.6 at 18 months, accompanied by evidence of reverse remodeling. A significant decrease in LV end-diastolic volume, LVESV, and LV mass was observed out to 5 years.20 Finally, the baseline NYHA class of 2.8 was reduced significantly to 2.2 at 2 years. In summary, for patients with primarily nonischemic advanced heart failure and severe LV dysfunction, mitral valve surgery has been shown to be safe, with a low operative mortality rate, and associated with significant reversal of LV remodeling compared with baseline as well as improvement in NYHA functional class.

was 14 mL/kg/min, and LV end-diastolic dimension was nearly 70 mm. The operative mortality rate was only 1.6%—especially noteworthy because it represents the outcomes for nearly 30 different centers. Twelve-month cumulative survival was 86.5%; at 2 years, the cumulative survival was 85.2%. A majority of patients underwent a complete, small annuloplasty repair. Mitral valve insufficiency was reduced from 2.7 at baseline to 0.6 at 18 months, accompanied by evidence of reverse remodeling. A significant decrease in LV end-diastolic volume, LVESV, and LV mass was observed out to 5 years.20 Finally, the baseline NYHA class of 2.8 was reduced significantly to 2.2 at 2 years. In summary, for patients with primarily nonischemic advanced heart failure and severe LV dysfunction, mitral valve surgery has been shown to be safe, with a low operative mortality rate, and associated with significant reversal of LV remodeling compared with baseline as well as improvement in NYHA functional class.

LV reverse remodeling also has been demonstrated in several studies as a result of mitral valve repair either alone or in combination with coronary artery revascularization for patients with ischemic disease. Braun and colleagues showed that the combination of mitral valve repair and CABG resulted in a significant decrease in LV end-diastolic volume up to 4 years after surgery.21 Fattouch and associates demonstrated, in a randomized study of CABG versus CABG and mitral valve repair, that the addition of mitral valve repair improves postoperative NYHA functional class and ventricular remodeling, decreases pulmonary arterial pressure, and leads to a decrease in hospitalization for heart failure.22 These same studies also showed low operative mortality rates for combined mitral valve surgery and coronary artery bypass procedures in patients with significant LV dysfunction and advanced heart failure symptoms.

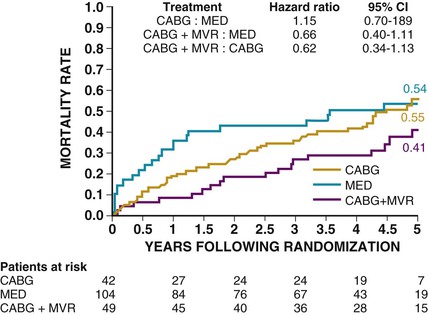

In the STICH trial, the decision to treat the mitral valve during CABG was left to the surgeon.23 Of 1212 patients who were randomly assigned, 435 (36%) had minimal MR, 554 (46%) had mild MR, 181 (15%) had moderate MR, and 39 (3%) had severe MR. In the medical arm, 70 deaths (32%) occurred in patients with minimal MR, 114 (44%) in those with mild MR, and 58 (50%) in those with moderate to severe MR. In patients with moderate to severe MR, there were 29 deaths (53%) among 55 patients randomly assigned to CABG who did not receive mitral surgery (HR versus medical therapy, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.77 to 1.87]) and 21 deaths (43%) among 49 patients who received mitral surgery (HR versus medical therapy, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.35 to 1.08). After adjustment for baseline prognostic variables, the hazard ratio for CABG with mitral surgery versus CABG alone was 0.41 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.77; P <.006), (Fig. 28-4). Although this was not a randomized trial between mitral valve surgery and CABG versus CABG alone, this retrospective analysis suggests a possible benefit to the concomitant surgical procedures.

In another study, 21 centers randomly assigned 75 patients to a CABG plus reduction mitral annuloplasty as a stratum in the control arm of the RESTOR-MV (Randomized Evaluation of a Surgical Treatment for Off-pump Repair of the Mitral Valve) trial, with a mean follow-up period of 24.6 months.24 Entry criteria included need for revascularization, presence of severe or symptomatic moderate functional ischemic MR, an LVEF of 25% or greater, an LV end-diastolic dimension of 7.0 cm or less, and more than 30 days since acute myocardial infarction. The 30-day mortality was 4.1% (3/73, [two patients were not randomly assigned]). Average degree of MR was reduced from 2.6 ± 0.8 preoperatively to 0.3 ± 0.6 at 2 years. The rate for freedom from death or valve reoperation was 78% ± 5% at 2 years. Significant improvement in LVEF and NYHA class, with reduction of LV end-diastolic dimension, was observed. Cox regression analyses suggested that increasing age and renal disease were associated with decreased survival.

Mitral valve repair can be accomplished with an investigational procedure involving percutaneous implantation of a clip that grasps and approximates the edges of the mitral leaflets at the origin of the regurgitant jet.25 Whether such less invasive procedures will change the management approach to patients with poor LV function and significant MR remains to be explored. A summary of recent guideline statements about surgery for MR in patients with heart failure is presented in Table 28-2.

Multiple studies suggest that the recurrent rates of MR after repair are approximately 30% to 40%. These studies generally fail to address ring selection and amount of downsizing as an important consideration for durable results in the ischemic MR population. Early failure with recurrent MR in patients with ischemic heart failure after CABG and annuloplasty ring probably was due to the use of a flexible band or ring. These results stand in sharp contrast with little recurrent MR seen up to 4 years later when a rigid ring has been downsized by two to four sizes. Spoor and colleagues found that the MR recurrence rate was 9.5% with a flexible ring versus 2.5% with a nonflexible ring in patients with a preoperative LVEF of less than 30% and no primary mitral disease.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree