Fig. 6.1

Occipitocervical dislocation following car accident. Hyperintense signal on T2-weighted MRI showing blood inside C0-C1 left (a) and right (b) joints. Frontal plane CT scan (c) showing increased distance between occipital condyles and C1 articular masses (white arrows). Occipitocervical posterior fusion on post-op x-rays (d)

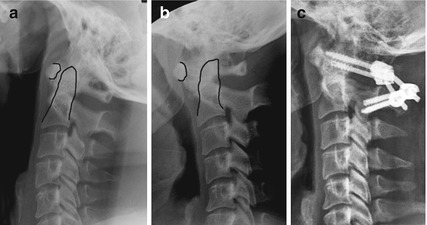

Fig. 6.2

C1-C2 sagittal instability due to transverse ligament injury. The distance between odontoid and atlas anterior arch increases in flexion (b) compared to extension (a). A C1-C2 posterior fusion is performed (c)

6.3 Lower Cervical Spine (LCS) Injuries (T1)

No worldwide accepted classification is found in the literature for these injuries, and no classification suits all the possible injuries a spine surgeon may encounter in his/her professional life. Most of the following consideration are drawn by Claude Argenson’s works [8, 9]. LCS injuries are divided in compression (type A), flexion-extension (type B), and rotation (type C) according to the possible pathogenesis. It is easy to keep in mind and can be easily related with radiologic evidence giving an immediate indication for surgery (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1

Indications for lower cervical spine injuries treatment are reported according to Argensons’ classification

Type | Severity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | |

A (compression) | CT | ACF | ACF |

B (flexion-extension) | CT | ADF | ADF + PF |

C (rotation) | CT or ADF | CT or ADF | ADF or PF + ADF |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree