Author (ref)

Year

No. of patients

Operative mortality %

Survival rates, 5 years (%)

Overall

NO

N1

N2

Piehler [8]

1982

66

15.2

32.9

54.0

7.4a

7.4a

Patterson [9]

1982

35

8.5

38.0

NS

NS

0.0

McCaughan [4]

1985

125

4.0

40.0

56.0

21.0a

21.0a

Ratto [93]

1991

112

1.7

NS

50.0

25.0

0.0

Allen [10]

1991

52

3.8

26.3

29.0

11.0

NS

Shah and Goldstraw [11]

1995

58

3.4

37.2

45.0

38.0

0.0

Downey [12]

1999

175

6.0

36.0

56.0

13.0

29.0

Facciolo [13]

2001

104

0.0

61.4

67.0

100.0

17.0

Magdeleinat [14]

2001

201

7.0

21.0

25.0

21.0

20.0

Burkhart [15]

2002

94

6.3

38.7

44.0

26a

26.0a

Chapelier [16]

2000

100

1.8

18

22

9

0

Riquet [17]

2002

125

7

22.5

30.7

0

11.5

Roviaro [18]

2003

146

0.7

NS

78.5

7.2a

7.2a

Matsuoka [19]

2004

97

NS

34.2b

44.2

40.0

6.2

The final area of controversy is whether radiation therapy, administered either pre- or postoperatively, is indicated in patients who have lung cancer that invade the chest wall. Potential benefits of preoperative therapy include the following: downstaging the tumor, allowing potentially unresectable tumors to be resected, decreasing the rate of close margins, and decreasing the risk of tumor spillage at the time of resection [20]. However, recent reports showed decreased survival rates in those patients who received radiation therapy [10, 14]. Currently, radiotherapy is proposed to reduce the incidence of local recurrence and should be reserved for patients with close surgical margins or those with hilar or mediastinal nodal involvement. Adjuvant chemotherapy had no apparent effect on survival, but the number of patients was too small to obtain statistically meaningful data.

Superior Sulcus Tumors

Superior sulcus lesions include a constellation of benign or malignant tumors extending to the superior thoracic inlet. They cause steady, severe, and unrelenting shoulder and arm pain along the distribution of the eighth cervical nerve trunk and first and second thoracic nerve trunks. They also cause Horner’s syndrome and weakness and atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, a clinical entity known as Pancoast-Tobias syndrome. Bronchial carcinoma represents the most frequent cause of superior sulcus lesions. Superior sulcus lesions of non-small cell histology account for less than 5 % of all bronchial carcinomas. These tumors may arise from either upper lobe and tend to invade the parietal pleura, endothoracic fascia, subclavian vessels, brachial plexus, vertebral bodies, and first ribs. However, their clinical features are influenced by their location. Tumors located anterior to the anterior scalene muscle may invade the platysma and sternocleidomastoid muscles, external and anterior jugular veins, inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, subclavian and internal jugular veins and their major branches, and the scalene fat pad. They invade the first intercostal nerve and first rib more frequently than the phrenic nerve or superior vena cava, and patients usually complain of pain distributed to the upper anterior chest wall.

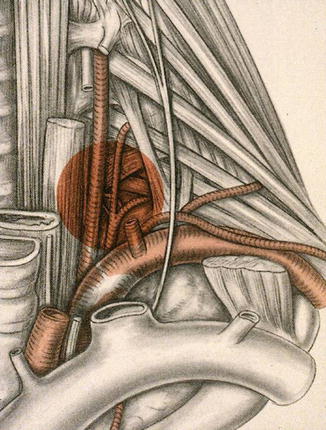

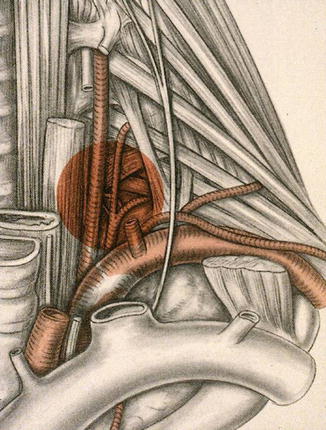

Tumors located between the anterior and middle scalene muscles may invade the anterior scalene muscle with the phrenic nerve lying on its anterior aspect; the subclavian artery with its primary branches, except the posterior scapular artery; and the trunks of the brachial plexus and middle scalene muscle (Fig. 7.1). As the tumor involves the brachial plexus, symptoms develop in the distribution of T1 (ulnar distribution of the arm and elbow) and C8 nerve roots (ulnar surface of the forearm and small and ring fingers).

Fig. 7.1

Schematic drawing of a left superior sulcus bronchial carcinoma invading the middle thoracic inlet, including the subclavian artery. The arrows show the limits of the orthopedical resection to have R0 margins

Tumors lying posterior to the middle scalene muscles are usually located in the costovertebral groove and invade the nerve roots of T1, the posterior aspect of the subclavian and vertebral arteries, paravertebral sympathetic chain, inferior cervical (stellate) ganglion, and prevertebral muscles. These posterior tumors can invade the transverse process and the vertebral bodies (only abutting the costovertebral angle or extending into the intraspinal foramen without intraspinal extension may yet be resected). Because of the peripheral location of these lesions, pulmonary symptoms, such as cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea, are uncommon in the initial stages of the disease. Abnormal sensation and pain in the axilla and medial aspect of the upper arm in the distribution of the intercostobrachial (T2) nerve are more frequently observed in the early stage of the disease process. With further tumor growth, patients may present with full-blown Pancoast syndrome.

Superior sulcus tumors are extremely difficult to diagnose at initial presentation. The time elapsed between the onset of the Pancoast-Tobias syndrome and diagnosis is still around 6 months. These patients usually present with small apical tumors that are hidden behind the clavicle and the first rib on routine chest radiographs. The diagnosis is established by history and physical examination, biochemical profile, chest radiographs, bronchoscopy and sputum cytology, fine-needle transthoracic or transcutaneous biopsy and aspiration, and computed tomography of the chest. If there is evidence of mediastinal adenopathy on chest radiographs, computed tomographic scanning, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan, histologic proof is mandatory because patients with clinical N2 disease are not suitable for operation. Neurologic examination, magnetic resonance imaging, and electromyography delineate the tumor’s extension to the brachial plexus, phrenic nerve, and epidural space. Vascular invasion is evaluated by venous angiography, subclavian arteriography, Doppler ultrasonography (cerebrovascular disorders may contraindicate sacrifice of the vertebral artery), and magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging has to be performed routinely when tumors approach the intervertebral foramina to rule out invasion of the extradural space.

The initial evaluation also includes all preoperative cardiopulmonary functional tests routinely performed before any major lung resection and investigative procedures to identify the presence of any metastatic disease.

Although it is now established that radical surgery represents the only hope for long-term survival and cure, optimal management for superior sulcus tumors continues to be a major challenge. The traditional approach to superior sulcus tumors has been preoperative radiotherapy followed by resection, although this standard was established 45 years ago solely on the basis of encouraging short-term survival as compared with historical controls [21]. Then, high-dose curative primary radiotherapy [22], “sandwich” preoperative and postoperative radiotherapy [23], postoperative radiotherapy alone [24], and intraoperative brachytherapy combined with preoperative radiation therapy and operation [25] have been reported as the treatment modalities of superior sulcus tumors. In 2001, SWOG 9416 (Intergroup 0160) [26] evaluated the role of induction chemoradiotherapy and surgery for patients with superior sulcus tumors in multi-institutional setting and updated their results in 2003 [27] for the treatment of these tumors. And then, preoperative concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been explored by several other groups [28, 29]. The rate of complete resection was 92 % as opposed to an average of 66 % among historical series of conventional treatment [26, 30]. The consistency of the data regarding preoperative chemoradiotherapy and regarding preoperative radiotherapy alone is convincing that preoperative chemoradiotherapy represents a new standard of care for patients with Pancoast tumors, although no randomized data are available comparing these approaches [31]. As to whether surgery should proceed or follow radiation therapy in newly diagnosed superior sulcus tumors, our strong opinion is to first resect, because dissecting on a previously (chemo)irradiated thoracic inlet unquestionably increases the technical difficulties and postoperative morbidity. Radiation therapy is to be discussed in the postoperative course.

Absolute surgical contraindications in the management of superior sulcus tumors are the presence of extrathoracic sites of metastasis, histologically confirmed N2 disease, and extensive invasion of the cervical trachea, esophagus, and the brachial plexus above the T1 nerve root; this is because it indicates that the tumor is locally too extensive to achieve a complete resection or that limb amputation is necessary. Invasion of the subclavian vessels should no longer be considered a surgical contraindication. Massive vertebral invasion, diagnosed preoperatively, is synonymous with unresectability. Invasions limited to the intervertebral foramen without extension into the spinal canal are resectable.

As a general rule, superior sulcus tumors not invading the thoracic inlet are completely resectable through the classic posterior approach of Shaw et al. [21] alone. Because the posterior approach does not allow direct and safe visualization, manipulation, and complete oncologic clearance of all anatomic structures that compose the thoracic inlet, superior sulcus lesions extending to the thoracic inlet should be resected by the anterior transcervical approach as described by Dartevelle et al. [24, 32]. This operative procedure is nowadays accepted as a standard approach for all benign and malignant lesions of the thoracic inlet structures, including nonbronchial cancers (e.g., osteosarcomas of the first rib and tumors of the brachial plexus), and for exposing the anterolateral aspects of the upper thoracic vertebrae. Contraindications to this approach include extrathoracic metastasis, invasion of the brachial plexus above the T1 nerve root, invasion of the vertebral canal and sheath of the medulla, massive invasion of the scalene muscles and extrathoracic muscles, mediastinal lymph node metastasis, and significant cardiopulmonary disease.

We also developed a technique for resecting posteriorly located superior sulcus tumors extending into the intervertebral foramen without intraspinal extension in collaboration with a spinal surgeon [33]. The underlying principle is that one can perform a radical procedure by resecting the intervertebral foramen and dividing the nerve roots inside the spinal canal by a combined anterior transcervical and posterior midline approach (Fig. 7.2). The reported surgical morbidity ranges from 7 to 38 % with surgical mortality generally around 5–10 % [34–48].

Fig. 7.2

Right-sided apical tumor involving the costotransverse space and intervertebral foramen and part of the ipsilateral vertebral body; this tumor is first approached anteriorly and then the operation is completed through an hemivertebrectomy performed through the posterior midline approach

The overall 5-year survival rates after combined radiosurgical (posterior approach) treatment of superior sulcus tumors due to bronchial carcinoma range from 18 to 56 % (Table 7.2). The best prognosis is found in patients without nodal involvement who have had a complete resection.

Table 7.2

Results of patients treated surgically for superior sulcus tumors

Author, year | No. of cases | 5-year survival (%) | Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Paulson, 1985 [35] | 79 | 35 | 3 |

Anderson, 1986 [36] | 28 | 34 | 7 |

Devine, 1986 [37] | 40 | 10 | 8 |

Miller, 1987 [38] | 36 | 31 | NS |

Wright, 1987 [39] | 21 | 27 | – |

Shahian, 1987 [23] | 18 | 56 | – |

McKneally, 1987 [40] | 25 | 51 | NS |

Komaki, 1990 [22] | 25 | 40 | NS |

Sartori, 1992 [41] | 42 | 25 | 2.3 |

Maggi, 1994 [42] | 60 | 17.4 | 5 |

Ginsberg, 1994 [43] | 100 | 26 | 4 |

Okubo 1995 [44] | 18 | 38.5 | 5.6 |

Dartevelle, 1997 [45] | 70 | 34 | – |

Martinod, 2002 [46] | 139 | 35 | 7.2 |

Alifano, 2003 [47] | 67 | 36.2 | 8.9 |

Goldberg, 2005 [48] | 39 | 47.9 | 5 % |

Total | 807 | 34.5 ± 11.7a | 5.6 ± 2.2a |

Carinal Resections

Refinement in techniques of tracheal surgery and bronchial sleeve lobectomy has made carinal resection and reconstruction possible. However, the potential for complications remains high and few centers only have cumulated sufficient expertise to safely perform the operation. Surgery is still infrequently proposed because of its complexity and the paucity of data demonstrating benefit in the long term. However, results from recent series demonstrate that carinal resection is safe in experienced centers with an operative mortality of less than 10 % and can be associated with good to excellent long-term survival in selected patients. The current results are considerably better than those from earlier reported series and likely account for the improvement in surgical and anesthetic techniques.

Careful patient selection and detailed evaluation of the lesion is a key component to good surgical results in carinal resection. All patients should be evaluated to ascertain that they can tolerate the operation and withstand the necessary removal of pulmonary parenchyma. The preoperative workup consists of chest radiography, chest computed tomography (CT) scan, pulmonary function tests, arterial blood gas, ventilation/perfusion scan, electrocardiography, and echocardiography. Stress thallium studies, maximum oxygen uptake, and exercise testing are used when indicated. The operation is an elective procedure and efforts should be made to prepare the patients for surgery with chest physiotherapy, deep breathing, and cessation of smoking. Airway obstruction, bronchospasm, and intercurrent pulmonary infection should be reversed. Steroids should be discontinued before surgery.

Flexible or rigid bronchoscopy is crucial to evaluate the overall length of the tumor, the adequacy of the remaining airway, and the feasibility of a tension-free anastomosis. Besides routine investigation to rule out extrathoracic metastasis for patients with bronchogenic carcinoma, we also routinely perform a mediastinoscopy at the time of surgery in patients presenting with bronchogenic carcinoma to exclude N2 or N3 disease.

Pulmonary angiography is performed for carinal tumors arising from the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, because invasion of right upper lobe (mediastinal) artery usually indirectly reveals invasion of the posterior aspect of the superior vena cava (SVC). Superior cavography is performed if the SVC is potentially involved. Transesophageal echography is occasionally performed to evaluate tumor extension to the posterior mediastinum, especially the esophagus or the left atrium.

Indications and Contraindications

The safe limit of resection between the lower trachea and the contralateral main bronchus is usually considered to be 4 cm. This is particularly important if a right carinal pneumonectomy is performed and the left mainstem bronchus is to be reanastomosed end to end to the distal trachea. Upward mobilization of the left mainstem bronchus is limited because of the aortic arch and can easily result in excessive anastomotic tension.

In patients with bronchogenic carcinoma, carinal resection should be considered for tumors invading the first centimeter of the ipsilateral main bronchus, the lateral aspect of the lower trachea, the carina, or the contralateral main bronchus. This applies usually for right-sided tumor, since left-sided tumor rarely extends up to the carina without massively invading structures situated in the subaortic space. The long-term results of carinal resection for patients with bronchogenic carcinoma and N2 or N3 disease are poor, and therefore, the findings of positive mediastinal nodes at the time of mediastinoscopy are usually considered a contraindication to surgery. Induction therapy may be offered for these patients, but we have found that this increases the technical difficulty of the operation and is associated with greater operative mortality, particularly if carinal pneumonectomy is required

Surgical Technique

Our technique of carinal resection has been reviewed in detail elsewhere [49, 50]. Only some specific points are presented herein. Ventilation during carinal resection has always been a major concern. Our technique is similar to Grillo et al. [51]. The patient is initially intubated with an extra-long armored oral endotracheal tube that can be advanced into the opposite bronchus if one-lung ventilation is desired. Once the carina has been resected, the opposite main bronchus is intubated with a cross-field sterile endotracheal tube connected to a sterile tubing system. The tube can be safely removed intermittently to place the sutures precisely.

Approaches

The incision varies according to the type of carinal resection.

Carinal resection without sacrifice of pulmonary parenchyma is approached through a median sternotomy. As previously reported by Pearson et al. [51–53], we find that this approach allows any type of pulmonary resection, including a left pneumonectomy.

For carinal resection with sacrifice of pulmonary parenchyma, the approach depends on the lung concerned by resection. On the right side, a right posterolateral thoracotomy in the fifth intercostal space gives perfect exposure of the lower trachea and the origin of both main bronchi. On the left side, exposure of the lower trachea and right main bronchus is hindered by the aortic arch; that is why the median sternotomy is our preferred approach for left carinal pneumonectomy.

Type of Carinal Resection

1.

Carinal resection without pulmonary resection

Carinal resection without pulmonary resection is limited to the tumors located at the carina or at the origin of the right or left main bronchus. Depending on the extent of invasion, different modes of reconstruction exist. For very small tumors implanted on the carina only, the medial wall of both main bronchi can be approximated together to fashion a new carina that is then anastomosed to the trachea (Fig. 7.3). When the tumor is more extensive, requiring a larger portion of the trachea to be resected, end-to-end plus end-to-side anastomosis is the method of choice.

Fig. 7.3

Carinal resection with “neo-carina” reconstruction. (1) Carinal lesion involving little of the trachea. Resection lines are indicated (1). The medial walls of the right and left main bronchi are approximated with interrupted 4-0 PDS sutures to form a new carina (2)

2.

Right carinal pneumonectomy

Right carinal pneumonectomy is the most frequent type of carinal resection for bronchogenic carcinoma.

3.

Carinal resection with lobar resection

This has to be done when the bronchogenic tumor can extend from the right upper lobe to the carina and lower tract.

4.

Left carinal pneumonectomy

The aortic arch greatly hinders performance of the anastomosis in left carinal pneumonectomy. In our experience, we have favored a median sternotomy over a left thoracotomy in the past few years if a left carinal pneumonectomy is anticipated [54].

The results of carinal resection for bronchogenic carcinoma have improved over time. Recent series have shown that carinal resection is relatively safe in experienced centers and can be associated with good long-term survival in selected patients [54–65]. The median operative mortality is less than 7 % and the median 5-year survival is 43.3 % in our experience (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

Mortality and 5-year survival rates after carinal pneumonectomy

Author, year | Number of patients | Operative mortality (%) | 5-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Jensik, 1982 [55] | 34 | 29 | 15 |

Deslauriers, 1989 [56] | 38 | 29 | 13 |

Tsuchiya, 1990 [57] | 20 | 40 | 59 (2 years) |

Mathisen, 1991 [58] | 37 | 18.9 | 19 |

Roviaro, 1994 [59] | 28 | 4 | 20 |

Dartevelle,1995 [60] | 60 | 6.6 | 43.3 |

Mitchell, 1999 [61]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|