Sudden Cardiac Death and Ventricular Tachycardia

DEFINITION OF SUDDEN CARDIAC DEATH

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is defined by 2006 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society (ACC/AHA/HRS) guidelines as the abrupt cessation of cardiac activity so that the victim becomes unresponsive, without normal breathing or circulation, which progresses to death in the absence of any corrective measures. The definition excludes noncardiac conditions such as pulmonary embolus, intracranial hemorrhage, or airway obstruction. However, it does not exclude nonarrhythmic deaths, as the terminal rhythm is often unknown.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SUDDEN CARDIAC DEATH

The incidence of SCD is estimated to be 300,000 to 400,000 per year in the United States. The mortality rate is high, with only 2% to 15% of patients reaching the hospital alive. Fifty percent of these hospitalized patients die before discharge. There is a high recurrence rate of 35% to 50%. More than 75% to 85% of SCDs are associated with ventricular arrhythmias. The most common arrhythmias are ventricular tachycardia (VT) (62%), torsades de pointes (TdP) (13%), primary ventricular fibrillation (VF) (8%), followed by bradycardia (7%). SCD is the first presentation of cardiac disease in 25% of patients. The incidence increases with age at an absolute incidence of 0.1% to 0.2% per year. Men are more commonly affected (3:1). SCD in patients < 35 years of age is most commonly associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). In patients >35 years old, SCD is most commonly associated with coronary artery disease. Determinants of survival are rapid external defibrillation and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Hospital-based cooling protocols are being increasingly adopted to improve the neurologic prognosis for sudden death survivors.

RISK FACTORS AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Risk factors include the following:

Prior cardiac arrest: high recurrence rate, up to 35% to 50% at 2 years

Prior cardiac arrest: high recurrence rate, up to 35% to 50% at 2 years

Syncope in the presence of coexisting cardiac diseases

Syncope in the presence of coexisting cardiac diseases

Reduced left ventricular (LV) function and congestive heart failure (CHF)

Reduced left ventricular (LV) function and congestive heart failure (CHF)

Ventricular premature contractions and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) post-myocardial infarction

Ventricular premature contractions and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) post-myocardial infarction

Myocardial ischemia and/or documented scar

Myocardial ischemia and/or documented scar

Conduction system disease

Conduction system disease

The pathophysiology is determined by trigger factors and an underlying substrate conducive to arrhythmia. The mechanism of SCD can be related to any of the following pathophysiologic mechanisms:

Anatomical reentry around scarred myocardium

Anatomical reentry around scarred myocardium

Functional reentry using a diseased His–Purkinje system, or areas of nonhomogeneous (anisotropic) conduction

Functional reentry using a diseased His–Purkinje system, or areas of nonhomogeneous (anisotropic) conduction

Ischemia, electrolyte imbalance, ion channel abnormalities, surges in neurosympathetic tone, antiarrhythmic drugs

Ischemia, electrolyte imbalance, ion channel abnormalities, surges in neurosympathetic tone, antiarrhythmic drugs

Rapid and irregular ventricular activation (i.e., atrial fibrillation [AF] with rapid ventricular response in Wolff–Parkinson–White [WPW]).

Rapid and irregular ventricular activation (i.e., atrial fibrillation [AF] with rapid ventricular response in Wolff–Parkinson–White [WPW]).

Bradycardic SCD is overall uncommon; however, it remains important in specialized situations like cardiac transplant recipients.

Bradycardic SCD is overall uncommon; however, it remains important in specialized situations like cardiac transplant recipients.

SUDDEN CARDIAC DEATH AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Coronary artery disease is present in 80% of those with SCD. Approximately 75% have a history of prior myocardial infarction (MI). Sudden death can be the first clinical manifestation in up to 25% of patients with coronary artery disease. Approximately 65% have three-vessel obstructive coronary disease. Risk factors include depressed LV systolic function and frequent ventricular premature depolarizations (VPDs). However, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) study demonstrated that suppression of VPDs with class IC medications resulted in higher mortality. Data from large clinical trials have identified groups of patients with coronary artery disease, depressed LV systolic function, and nonsustained ventricular arrhythmias at increased risk for SCD, as discussed later in this chapter.

NONISCHEMIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

Patients with impaired LV systolic function in the absence of coronary artery disease are at increased risk for ventricular tachyarrhythmias and SCD, particularly those with symptomatic heart failure. In the heart failure population, total mortality is approximately 25% at 2.5 years, with SCD accounting for 25% to 50% of these cases. Mortality due to SCD is much higher in New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes II and III than in class IV patients, who have excess mortality due to pump failure.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Fifty percent of deaths in this patient subgroup are arrhythmic. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is predictive of sudden death, due to either circulatory failure or fatal arrhythmia. Ventricular ectopy is very common and does not appear to be as predictive of SCD as it is in patients with coronary artery disease. Up to 80% of patients may have NSVT on Holter monitoring. Inducibility for ventricular tachyarrhythmias at the time of electrophysiologic (EP) study is also less predictive when compared to patients with coronary disease and has almost no role in risk stratification. While some modalities such as abnormal microvolt T-wave alternans and heart rate variability have been associated with increased risk in this population, only LVEF ≤35% and the presence of symptomatic heart failure are recommended by practice guidelines for the purposes of risk stratification, particularly regarding selecting candidates for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

HCM is an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetrance associated with ever-increasingly discovered genetic mutations. The overall incidence of SCD is 2% to 4% in adults and up to 6% in children. It is the most common cause of SCD in young athletes. Maron et al. have identified factors associated with increased risk such as the presence of NSVT, hypotension with exercise, unexplained syncope, septal thickness >3 cm, and a family history of sudden death in a first-degree relative younger than 50 years old. Among patients with HCM and primary prevention ICDs, appropriate therapy was uncommon among patients with none of these risk factors and occurred in 14% of patients with one risk factor, 11% in patients with two risk factors, and 17% in patients with three or more risk factors. In addition, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been increasingly utilized for risk stratification in HCM patients as the presence of basal septal scar is associated with VT as well as histopathologic changes. The role of genetic testing for risk stratification has not been established despite the identification of certain high-risk mutations, such as the LAMP2 gene.

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

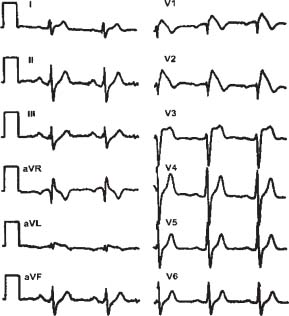

Progressive fibrofatty right ventricular tissue replacement is the pathologic hallmark of this disease. There is a strongly familial pattern; its prevalence may be up to 20% worldwide for SCD in young patients (U.S. 3%). MRI is the most useful imaging modality to make the diagnosis. Characteristic epsilon waves may be present on the electrocardiogram (ECG), as shown in Figure 27.1. The frequency and the severity of ventricular arrhythmias in this disease are progressive, thus making these patients candidates for ICD implantation.

FIGURE 27.1 ECG reading in ARVD.

INHERITTED AND ACQUIRED CHANNELOPATHIES

Long-QT Syndrome

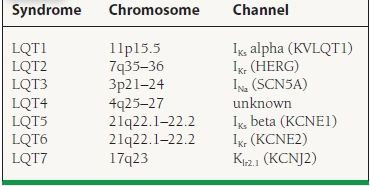

Long-QT syndrome consists of the inherited abnormalities that prolong cardiac repolarization as measured by the corrected QT (QTc) interval on surface ECG, which confer an increased risk of SCD by polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PMVT) or TdP. There are numerous identified mutations involving mostly sodium and potassium ion channels (Table 27.1). Abnormal QTc cutoff values are commonly selected as >440 milliseconds in men and >460 milliseconds in women, although actual cardiac events occur on a skewed curve and are highest among patients with QTc > 500 milliseconds. The most common symptoms associated with long QT syndrome are palpitations and syncope, although associations also exist with seizure disorders. Characteristic clinical triggers for arrhythmia events have been described by genotype including exercise or swimming (LQT1), auditory stimuli, or during the postpartum period (LQT2) and during sleep (LQT3). Features associated with higher risk for SCD include the Jervel and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (congenital deafness), syncope or ventricular arrhythmias while on beta-blocker therapy, QTc > 500 milliseconds with an LQT1 or LQT2 genotype, female gender, and family history of SCD. Standard treatment includes beta-blocker therapy, but this remains somewhat controversial in the case of LQT3, where the clinical response rate is lowest. According to 2008 ACC/AHA/HRS device therapy guidelines, patients with syncope or ventricular arrhythmias while on beta-blocker therapy can be considered for primary prevention ICD implantation. The 5-year sudden-death risk in patients on beta-blocker therapy (Long QT Registry) is <1% in asymptomatic patients, 3% in the syncope group, and 13% in the SCD group. Mexiletine, a sodium channel blocker, may be helpful in reducing the burden of ventricular arrhythmias among patients with LQT3, due to the attributable gain-of-function mutation in SCN5A resulting in voltage-gated sodium channels remaining open longer than normal.

TABLE

27.1 Familial Long-QT Syndromes

A prolonged QT interval can also be acquired and secondary to other causes:

Electrolyte derangements

Electrolyte derangements

Acute hypokalemia

Acute hypokalemia

Chronic hypocalcemia

Chronic hypocalcemia

Chronic hypokalemia

Chronic hypokalemia

Chronic hypomagnesemia

Chronic hypomagnesemia

Medical conditions

Medical conditions

Bradyarrhythmias (complete heart block, sick sinus syndrome, bradycardia)

Bradyarrhythmias (complete heart block, sick sinus syndrome, bradycardia)

Cardiac (myocarditis, tumors)

Cardiac (myocarditis, tumors)

Endocrine: hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, pheochromocytoma

Endocrine: hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, pheochromocytoma

Neurologic (cerebrovascular accident, encephalitis, head trauma, subarachnoid hemorrhage)

Neurologic (cerebrovascular accident, encephalitis, head trauma, subarachnoid hemorrhage)

Nutritional (alcoholism, anorexia nervosa, liquid-protein diet, starvation)

Nutritional (alcoholism, anorexia nervosa, liquid-protein diet, starvation)

Drugs

Drugs

Antiarrhythmics: class IA (disopyramide, procainamide), class III (sotalol, dofetilide)

Antiarrhythmics: class IA (disopyramide, procainamide), class III (sotalol, dofetilide)

Tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, desipramine)

Tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, desipramine)

Antifungals (itraconazole, ketoconazole)

Antifungals (itraconazole, ketoconazole)

Antihistamines (astemizole, terfenadine)

Antihistamines (astemizole, terfenadine)

Antimicrobials (Bactrim, E-mycin, pentamidine)

Antimicrobials (Bactrim, E-mycin, pentamidine)

Neuroleptics (phenothiazines, thioridazine)

Neuroleptics (phenothiazines, thioridazine)

Organophosphate insecticides

Organophosphate insecticides

Promotility agents (cisapride)

Promotility agents (cisapride)

Oral hypoglycemics (Glibenclamide)

Oral hypoglycemics (Glibenclamide)