30 Sudden Cardiac Death

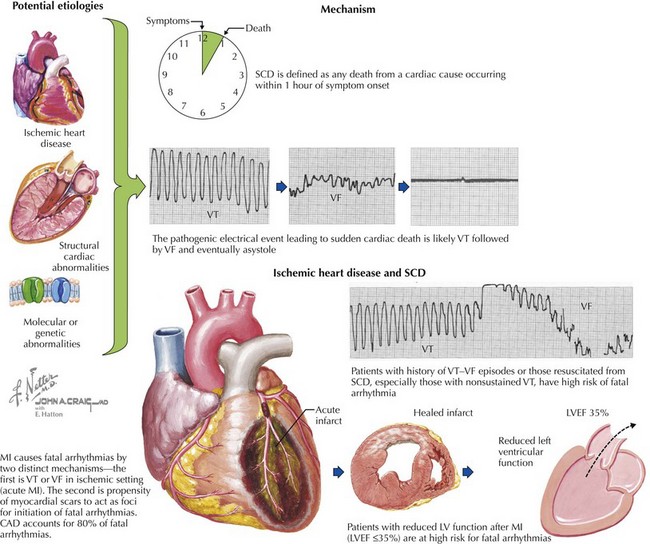

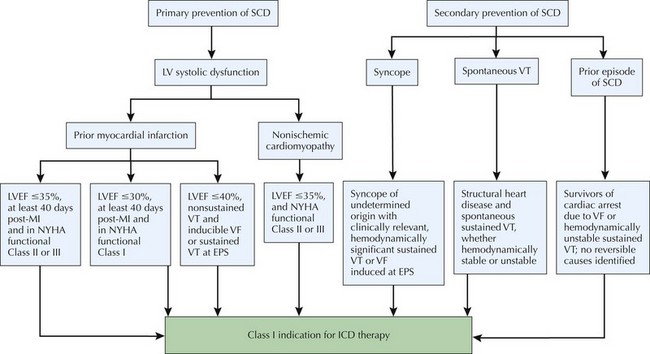

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is defined as any death from a cardiac cause occurring within an hour of symptom onset. SCD occurs in 300,000 to 450,000 individuals in the United States annually, which translates to an overall incidence of 0.1% to 0.2% per year. The term SCD is also used to refer to an event from which an individual is resuscitated or spontaneously recovers—events probably more appropriately termed cardiac arrest. SCD has many potential etiologies (Box 30-1). Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and prior myocardial infarction (MI) have an annual incidence of SCD of up to 30% and are responsible for approximately 70% of fatal arrhythmias. Other high-risk groups include patients with prior cardiac arrest, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy (dilated, infiltrative, or hypertrophic), valvular heart disease, myocarditis, and congenital heart disease. Screening patients potentially at risk for SCD and addressing their risk factors is the crux of primary prevention. Secondary measures aim to prevent recurrent events in survivors of aborted SCD (Fig. 30-1).

Box 30-1 Major Etiologies of Sudden Cardiac Death

RV, right ventricular; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 30-1 Treatment algorithm for ICD-based primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Etiology and Risk Factors

The pathogenic electrical events leading to SCD are most commonly ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), and eventually asystole (Fig. 30-2). Approximately 80% of SCDs involve VT, VF, or torsades de pointes; the remaining 20% are due to bradyarrhythmias. SCD is most commonly associated with underlying structural heart disease. Less than 20% of out-of-hospital victims of SCD recover to hospital discharge. The likelihood of resuscitation diminishes 10% for every minute of delay. It has been estimated that 50% of those who survive a cardiac arrest will die within 3 years. This underscores the importance of primary and secondary prevention.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common etiologies are discussed in the sections that follow (see also Box 30-1).

Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy

Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Ten to fifteen percent of SCD cases are attributable to cardiomyopathies not associated with CAD. In patients with dilated cardiomyopathies, the presence of nonsustained VT, syncope, and/or advanced heart failure are high-risk predictors. SCD is the major cause (up to 72% in some studies) of death in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Most fatal arrhythmias are thought to be tachyarrhythmias, mainly polymorphic, and less commonly monomorphic, VT. The primary mechanism of polymorphic VT and VF is unknown, but subendocardial scarring and interstitial and perivascular fibrosis are probably involved. A particular type of monomorphic VT (see Chapter 29) caused by bundle branch reentry is characteristic of nonischemic cardiomyopathy. In bundle branch reentry, a “macro” reentrant circuit involving both bundles, the Purkinje system, and the myocardium can be documented.

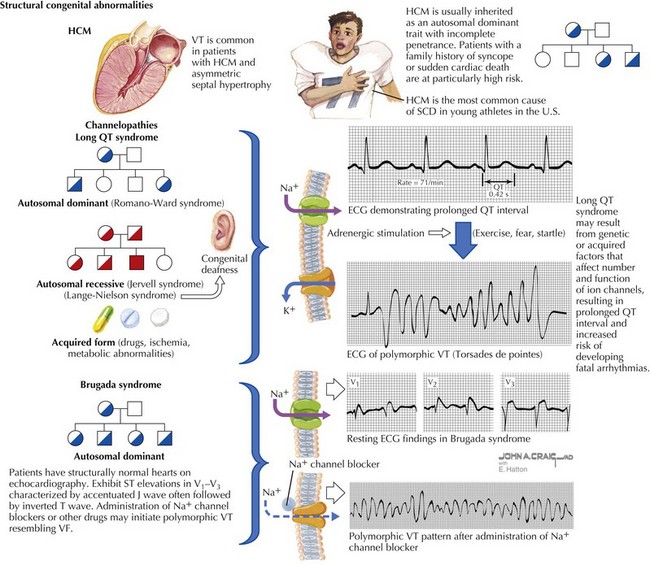

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder estimated to affect 1 in 500 adults (see Chapter 19 and Figure 30-3). The overall risk of SCD in patients with HCM is estimated at 1% to 4% per year, but within subgroups of patients with this disease the risk of SCD varies substantially. All first-degree relatives of a patient with HCM who had SCD must be screened. Generally, patients with HCM who are at highest risk for SCD are those with recurrent syncope, nonsustained VT on Holter monitoring, extreme left ventricular hypertrophy on echocardiogram (>30 mm), abnormal blood pressure response to exercise, and a positive family history of SCD from HCM. Careful evaluation for HCM is of utmost importance in young individuals because HCM is the most common cause of SCD in young athletes in the United States (Fig. 30-3, top). Genetic testing of first-degree relatives of an individual whose gene mutation has been identified may help establish risk but remains a controversial screening modality. Screening should include a detailed history and physical examination, ECG, and echocardiography.

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia and Cardiomyopathy

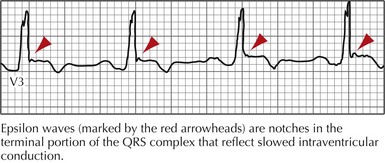

The ECG may reveal left bundle branch morphology and left-axis deviation during VT, and epsilon waves and T-wave inversions in leads V1 through V3 during sinus rhythm (Fig. 30-4). The most useful imaging study to confirm the diagnosis of ARVD/C is MRI, which classically shows fatty infiltration of the myocardium, RV dilatation or dyskinesia, or both, but if nondiagnostic, additional confirmatory tests may be required.

Other Congenital Anomalies

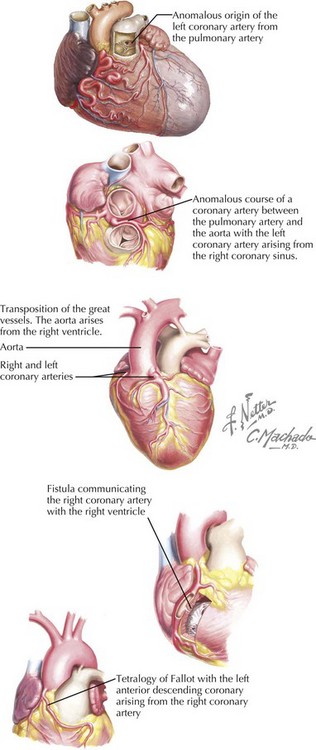

Coronary artery anomalies are uncommon but account for a disproportionate percentage of deaths in young athletes. The mechanism of SCD is thought to be ischemia from coronary spasm or abnormal tension placed on the ectopic coronary artery by the ascending aorta and the pulmonary trunk (Fig. 30-5). The most consistently fatal anomaly occurs when the left coronary artery originates from the right coronary sinus and courses between the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Primary Electrophysiology Disorders

Long QT Syndrome

Channelopathies account for up to 5% to 10% of SCDs annually but generate considerable interest because these patients have structurally normal hearts. The most recognized of the channelopathies are manifested by prolongation of the QT interval with a concomitant increased risk of VT and SCD. Long QT syndrome (LQTS) encompasses patients with QTc intervals greater than 440 milliseconds (Fig. 30-3, middle) and can be congenital or acquired. The annual incidence of SCD is between 1% to 2% and approximately 9% in affected individuals with syncope. Life-threatening arrhythmia presents as torsades de pointes. Torsades de pointes, or “twisting of the point,” is polymorphic VT associated with a prolonged QT interval, R-on-T premature ventricular contractions, and long-short coupled R-R intervals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree