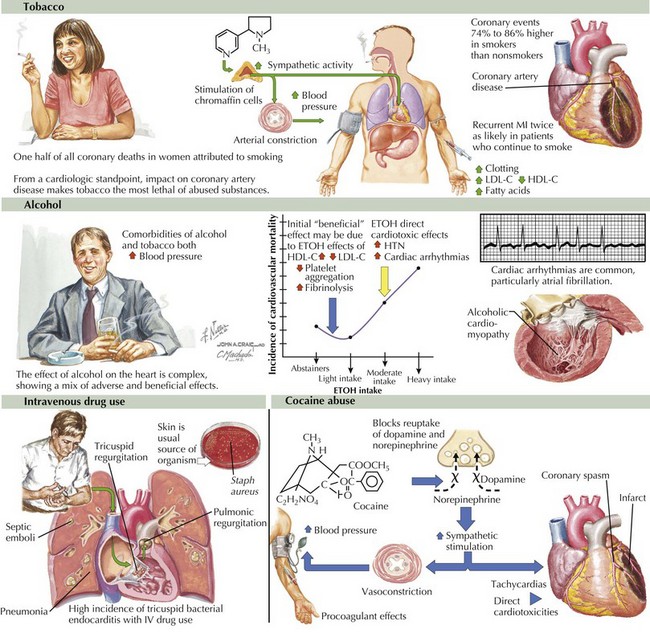

65 Substance Abuse and the Heart

Substance abuse has enormous social, economic, and medical consequences. Although abuse of both legal and illegal substances can have adverse effects on the cardiovascular system, as discussed in this chapter, it is important to note that two legal substances—tobacco and alcohol—have the greatest impact on cardiovascular health of citizens of the United States and other industrialized countries (Fig. 65-1, upper and middle).