Chapter 59

Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack

1. What is stroke? How common is stroke? How common is it in the setting of cardiac disease?

2. What is a transient ischemic attack, and why is the clinical recognition of it important?

3. What are the major causes of stroke and TIA?

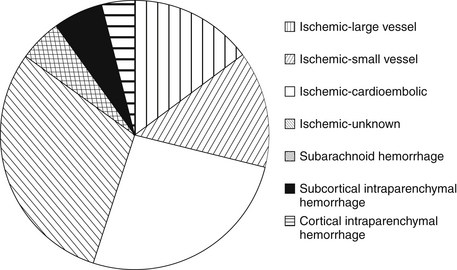

The major etiologies of ischemic stroke are cardioembolism, small vessel vasculopathy leading to lacunar stroke, and large vessel atherosclerosis (including intracranial atherosclerotic plaque rupture, as well as embolization from large arteries, such as the carotid, vertebral, and basilar arteries, to cerebral arteries [Fig. 59-1 and Table 59-1]). Hemorrhagic strokes include subarachnoid hemorrhage (usually due to aneurysm rupture) and intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Intraparenchymal hemorrhages are classified by their location: subcortical (associated with uncontrolled hypertension in 60% of cases) versus cortical (more concerning for underlying mass, arteriovenous malformation, or cerebral amyloid angiopathy; see Fig. 59-1). Figure 59-2 summarizes the major causes of stroke and their relative frequency.

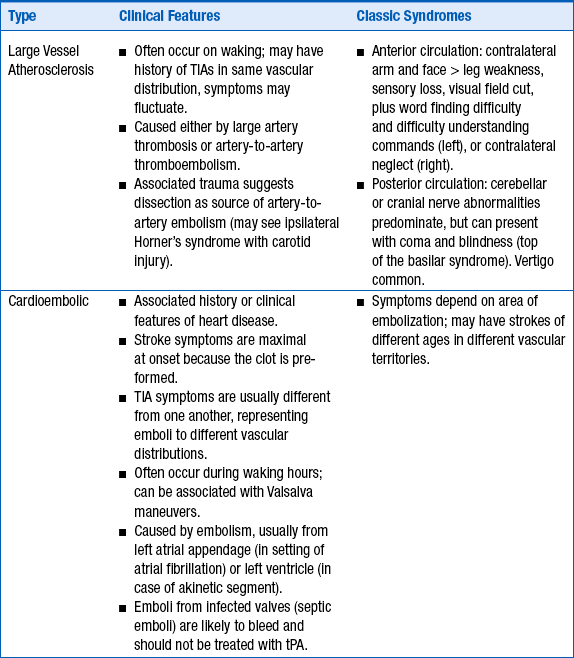

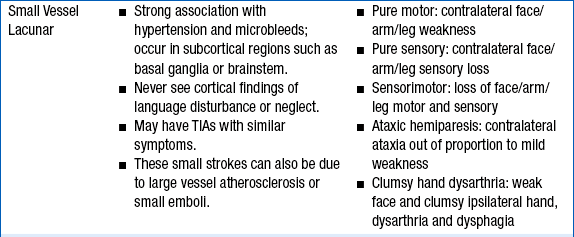

TABLE 59-1

CLINICAL FEATURES OF THE THREE MOST COMMON TYPES OF STROKE

TIA, transient ischemic attack; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

Figure 59-1 The computed tomographic findings of strokes and stroke mimics. A, Lacunar ischemic stroke, typical of small vessel disease; B, multiple ischemic strokes of different ages, typical of cardioembolism; C, Subcortical intraparenchymal hemorrhage; D, cortical intraparenchymal hemorrhage; E, subarachnoid hemorrhage; F, subdural hematoma, with a small amount of subarachnoid hemorrhage along the falx (arrow).

Figure 59-2 Relative frequencies of different types of stroke. (Compiled using data from the Greater Cincinnati Northern Kentucky Stroke Study.)

Among the other potential causes of stroke, dissection of the blood vessels needs to be considered, especially if there is face or neck pain or a history of trauma. Illicit drug use is a possible cause of either ischemic stroke (cocaine-, stimulants-, or “bath salts”–induced spasm) or hemorrhagic stroke (as a result of vascular injury or sudden massive increase in blood pressure). Patent foramen ovale (PFO) remains a controversial cause of stroke (see Question 18). Other, rarer, causes of stroke include hypercoagulable states (e.g., lupus and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome) and genetic disorders, such as homocystinuria and fibromuscular dysplasia.

4. How are stroke and TIA diagnosed?

Stroke and TIA are diagnosed clinically, and no imaging correlation is usually required for the diagnosis, although imaging procedures are performed to rule out other causes, such as tumor. Focal neurologic deficits with sudden onset should be considered as a vascular event until proven otherwise because of the possibility of recurrence or progression of the deficit. Focal weakness, numbness, facial asymmetry, or speech difficulties are classic presentations. Altered level of consciousness, vertigo, and cranial nerve deficits are often seen with vertebrobasilar-brainstem strokes. See Table 59-1 for lists of the clinical signs and symptoms of the major subtypes of stroke: large vessel atherosclerosis and thrombosis, cardioembolic stroke, and small vessel stroke.

5. What should be done in cases of suspected stroke or TIA?

A head CT must be performed immediately to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic strokes (see Fig. 59-1) because these are managed very differently. The CT itself does not diagnose stroke; it is primarily used to rule out causes other than ischemic stroke, including hemorrhagic infarction, tumor, subdural hematoma, and other causes. Figure 59-1 demonstrates the CT findings of strokes and stroke mimics.

6. How are ischemic acute strokes treated?

tPA

The only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute ischemic strokes is intravenous (IV) tPA, administered within 3 hours of symptom onset. Based on the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III), American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend treatment with IV tPA in selected patients out to 4.5 hours after symptom onset, but this is not yet approved by the FDA. Note, however, that the earlier tPA is given, the better the clinical outcome. The greatest benefit of tPA occurs at earlier time points. It is critical to give tPA as soon as possible if head CT does not reveal signs of hemorrhage or hypodensity. Only tPA is approved for acute stroke thrombolysis. Only eight stroke patients need to be treated with IV tPA to result in one patient with complete or near-complete recovery, and this number needed to treat (NNT) takes into account the increased risk of hemorrhage after tPA administration. Patients of any age benefit from tPA. Contraindications to IV tPA for the treatment of stroke are given in Box 59-1. Although tPA administration is not contraindicated in the setting of moderately elevated international normalized ratios (INR of 1.3-1.7), recent studies suggest an increased risk of brain hemorrhage compared to tPA administraton with a normal INR. Importantly, patients who have their strokes after cardiac catheterization and who meet these criteria may still benefit from tPA, despite the recent administration of heparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, although this is outside the usual protocols and should be done only with expert help. In this situation, various treatments have been reported, including intraarterial therapy or IV abciximab, but these uses remain investigational.