Smoking Cessation

Beth C. Bock

Effects of Smoking on Health

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality among all racial and ethnic groups in the United States (1,2). Tobacco use is the primary cause of lung cancer and is causally linked to other forms of cancer (3,4), heart disease, stroke (5), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6,7), and it is responsible for more than $75 billion in annual health care expenditures (8). Each year in the United States, more than 438,000 deaths are linked to cigarette smoking, and one-third of deaths among former smokers are directly attributable to tobacco use (9). Moreover, environmental tobacco smoke or “secondhand smoke” has been strongly associated with respiratory illness in children and with both cancer and heart disease in adults living with smokers. Approximately 21.6% of U.S. adults are current smokers (10). Although this prevalence is lower than the 22.5% prevalence among U.S. adults in 2002 (11), the rate of decline is not sufficient to meet the national health objective for 2010.

Smoking Cessation in Cardiac Patients

Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of mortality in the United States, accounting for nearly one-third of all deaths (12). Cigarette smoking greatly increases the risk of death from heart disease, and smoking cessation produces marked reductions in cardiovascular risk (6). The experience of hospitalization, particularly for cardiovascular disease, can result in smoking cessation even without intervention (13,14,15). However, cessation rates vary greatly, depending on the reason for hospitaliza-tion, length of stay, and the presence of depressive symptoms (16,17). For example, Rigotti et al found high cessation rates (58%) 1 year after hospitalization among patients having coronary bypass surgery, whereas other studies have shown low cessation rates among smokers immediately after hospitalization (13.7%) and at 1-year follow-up (9.2%) (18,19). Most individuals who quit smoking without intervention will relapse within 6 months (17,20).

Physician Interventions

Although 70% of smokers visit a physician each year, relatively few doctors use this opportunity to address the patient’s smoking (21,22,23). Physicians practicing in specialties such as cardiology or emergency medicine are less likely to provide smoking cessation interventions than primary care physicians (24). Possible explanations cited for low physician intervention rates include lack of time, deficient training in counseling skills, and an absence of organizational supports (25,26,27,28). This is regrettable because multiple studies have shown that even a brief intervention lasting less than 3 minutes significantly increases the chance that the smoker will quit (22,29). Formal physician training, the use of cues or reminders, pharmacologic aids, follow-up visits, and supplemental educational materials all increase the effectiveness of physician-delivered interventions (22,30). Cardiologists seeing smokers with coronary artery disease, hypertension, or histories of recurrent chest pain can be especially effective because the patient’s illness can be linked directly to smoking. The clinical encounter is an important opportunity to address smoking cessation and should not be missed (31). Many physicians, however, do not feel that they have the counseling skills or training to address the issue of smoking cessation effectively. This chapter provides a well-researched, effective, and simple approach that cardiologists can use to counsel their patients who smoke.

Treatment Approaches

Clinical guidelines have been developed through a joint collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) together with the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the University of Wisconsin Medical School Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention (29). The recommendations made as a result of this extensive, systematic review and analysis of the extant peer-reviewed scientific literature form the basis of the approach taken in this chapter.

The key principles underlying these recommendations are

Physicians should identify all their patients who smoke.

Effective treatment is available for tobacco dependence.

Physicians should offer treatment to all their smoking patients who are ready to quit.

Physicians should offer treatment even to those smoking patients who are not yet ready or willing to quit because the physician’s intervention has been shown to increase the smoker’s readiness and motivation to quit.

The physician should understand that tobacco dependence is a chronic condition that typically requires repeated intervention before long-term success is achieved.

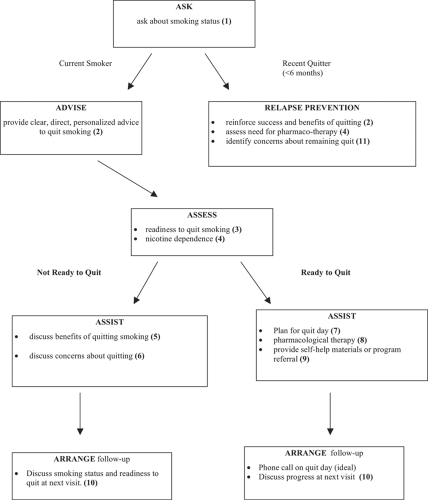

The best practice model for a brief intervention for smoking cessation is easily summarized by the mnemonic device of the “Five As” (Table 26-1). Each of these—Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange follow-up—is summarized in the following paragraphs (Fig. 26-1).

Ask

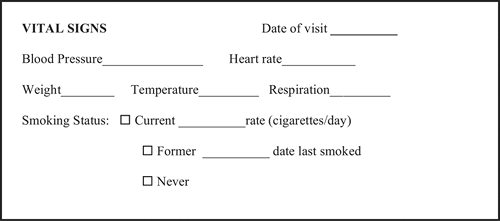

National guidelines recommend that physicians systematically determine the smoking status of all patients at every visit. This can be done by modifying the routine vital signs charting (Fig. 26-2).

Advise

Every tobacco user should be given clear, strong, and personalized advice to quit. Unfortunately, research has repeatedly shown that smoking counseling is not provided at most physician visits (26). Moreover, specialists are less likely to provide smoking counseling than primary care physicians (32).

Counseling does not need to be extensive to be effective. Brief, clear advice from a physician has been shown to double quit rates (29). For example, advice to a patient who is currently enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation might sound like this:

Clear: “It is important for you to quit smoking.”

Strong: “Because you have already experienced heart disease (or specify condition), the most important thing you can do to avoid repeating this experience is to quit smoking.”

Personal: “Your exercise capacity and your ability to be physically active will improve much faster if you quit smoking.”

Other phrases that work are: “As your physician, I want you to know that the most important thing you can do to protect or improve your health is to quit smoking.” “Quitting smoking is important for everyone who smokes, but for you its especially important because of (specify current health problem).”

Table 26-1. The Five as to Intervention in Smoking Cessation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Assess

Assess the patient’s readiness to quit smoking and level of nicotine dependence.

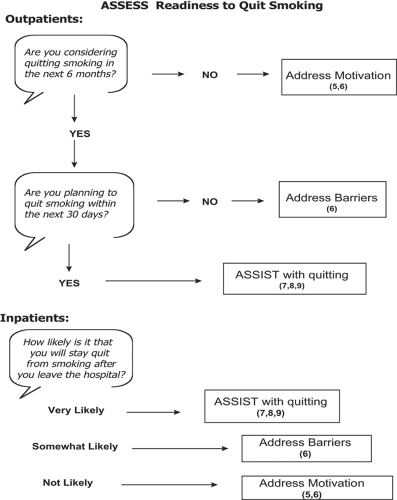

Readiness to Quit Smoking

Readiness to quit smoking is a key determinant of the treatment approach (Fig. 26-3). Treatment for smokers who are ready to make a serious attempt to quit should be focused on behavioral strategies, including (a) selecting a target quit date, (b) reviewing and arranging appropriate pharmacologic therapies, and (c) referring to self-help or professional programs. Treatment for smokers who are not ready to quit should focus on helping the patient get ready to quit. Treatment for these smokers should focus on the psychological issues surrounding cessation, including reasons for quitting versus reasons for continued smoking, concerns about the cessation process, building the patient’s self-confidence, and discussing family or social supports and barriers to quitting.

Motivation, or readiness to quit smoking, has most often been measured using Prochaska and DiClemente’s stages of change model (33), which was developed for use in outpatient populations. Because smoking restrictions in the in-patient setting and hospitalization encourage serious thought about smoking habits, this algorithm may tend to misclassify hospitalized smokers as having more motivation to quit than they actually do. Research has shown that asking inpatients a single question regarding how likely it is that they will remain abstinent after hospital discharge may be more predictive of actual motivation (34).

Nicotine Dependence

The most widely used and validated measure of nicotine dependence is the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (Table 26-2). Patients scoring 6 or more are highly nicotine dependent. It is important to know the level of nicotine dependence because, although research shows that most smokers benefit from nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), providing NRT is especially important for highly dependent smokers. Overall, smokers who use nicotine replacement show double the success rates as those who do not (29,35). Highly nicotine-dependent smokers are three times more likely to be successful if they use nicotine replacement. Moreover, the physician should choose the initial dose of NRT after considering the patient’s level of nicotine dependence.

Assist

Motivational Approaches

Many different types of smokers exist. To simplify, however, consider smokers as falling into one of two groups: those who are ready to quit and those who are not yet ready. Research studies have repeatedly shown that physicians who take a motivational approach to addressing smoking with their patients are more successful in helping these smokers to quit. Motiva-tional approaches, including the “transtheoretical” or “stages of change” model and motivational interviewing, are widely used theoretical models of how people change health behaviors

(33,36). Developed for use in outpatient populations, the basic tenet of these models is that individuals who are not yet ready to change behavior need to be approached differently than those who are ready to change. In practical terms, this means that treatment goals for smokers who are not yet ready to quit should focus on identifying reasons to quit, enhancing motivation for quitting, and identifying perceived barriers. Treatment for these smokers should avoid immediate behavioral goal setting (e.g., discussing quit dates or selecting phar-macologic treatments). Conversely, interventions for smokers who are ready to quit should focus on behavioral goals (e.g., choosing a target quit date and pharmacotherapy) and coping strategies.

(33,36). Developed for use in outpatient populations, the basic tenet of these models is that individuals who are not yet ready to change behavior need to be approached differently than those who are ready to change. In practical terms, this means that treatment goals for smokers who are not yet ready to quit should focus on identifying reasons to quit, enhancing motivation for quitting, and identifying perceived barriers. Treatment for these smokers should avoid immediate behavioral goal setting (e.g., discussing quit dates or selecting phar-macologic treatments). Conversely, interventions for smokers who are ready to quit should focus on behavioral goals (e.g., choosing a target quit date and pharmacotherapy) and coping strategies.

Concerns about Quitting

Many patients are aware that they should quit smoking, but have concerns about the process of quitting or are discouraged from prior failed attempts. These patients may benefit by exploring their concerns about quitting. The decisional balance worksheet has been used in numerous smoking cessation trials to help smokers identify both their reasons for wanting to quit and perceived barriers to quitting (Table 26-3).

Not Ready to Quit

Patients who are not yet ready to quit need help identifying reasons to quit, improving their motivation and confidence in

their ability to quit, and identifying barriers to smoking cessation. These patients may lack, or believe they lack, the financial resources to afford NRT or pharmacologic aids to quitting or information about how smoking is affecting their health. They may have concerns about quitting—possibly related to prior failed attempts (38). The physician can intervene with these patients by providing relevant information that will help them identify barriers to quitting and find the resources necessary to support cessation. Motivational interventions are most successful when the physician is empathic, promotes patient autonomy (provides choices among options), supports the patient’s sense of self-confidence, and avoids argumentation (39,40).

their ability to quit, and identifying barriers to smoking cessation. These patients may lack, or believe they lack, the financial resources to afford NRT or pharmacologic aids to quitting or information about how smoking is affecting their health. They may have concerns about quitting—possibly related to prior failed attempts (38). The physician can intervene with these patients by providing relevant information that will help them identify barriers to quitting and find the resources necessary to support cessation. Motivational interventions are most successful when the physician is empathic, promotes patient autonomy (provides choices among options), supports the patient’s sense of self-confidence, and avoids argumentation (39,40).

Table 26-2. Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree