Fig. 58.1

Small-bore chest catheters of different sizes

Fig. 58.2

Pigtail catheter

Image Guidance

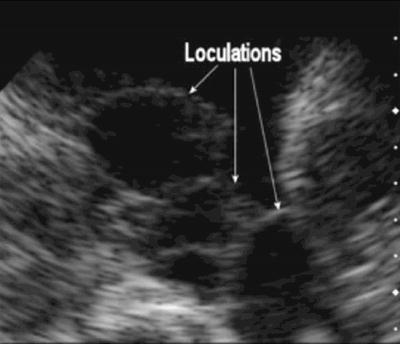

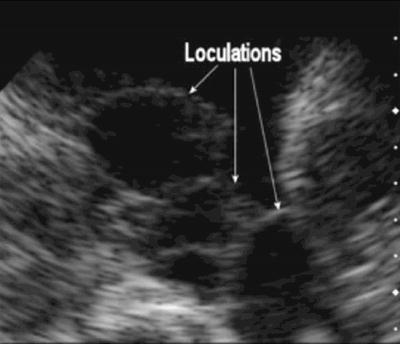

Imaging of the pleural space is a vital part of pleural intervention. It gives an initial idea about the viscosity of the pleural fluid and the complexity of the pleural space, which helps in the pre-procedure planning such as choosing the appropriate SBCC size and the entry site. In addition, if the parietal pleura is seen to be thickened and inflamed, one would anticipate a rough catheter introduction and thus may apply more generous local anesthesia to avoid patient’s pain and discomfort. During the procedure, image guidance helps to avoid catheter malposition in relation to fluid loculations. By using modern cross-sectional guidance techniques, primarily CT and ultrasound (Fig. 58.3), it is relatively easy to place the drainage catheters into specific loculations of fluid regardless of the size or location of the collection (Fig. 58.4). Finally, in case of multiple loculations, several catheters can be placed at the same setting under image guidance. This is the single most significant advantage of image-guided over non-guided thoracostomy, and its importance should not be underestimated.

Fig. 58.3

Portable ultrasound machine (M-turbo, SonoSite, Inc., USA)

Fig. 58.4

Loculated pleural effusion

Indications

Pleural Space Infection

Pleural space infections are associated with considerable morbidity, mortality, and health care resource use (Table 58.1). Drainage of the pleural space is the key component of care; however, the modality and extent of drainage and debridement has long been debated. Options include nonoperative (thoracentesis and tube thoracostomy with or without intrapleural thrombolytic therapy) and operative (thoracotomy or VATS) intervention. The approach to pleural space infection varies significantly between physicians reflecting differences in specialization, access to thoracic surgeons, and conventional wisdom and training.

Table 58.1

Selected indications for SBCC insertion

Indication |

1. Pneumothorax |

All patients on mechanical ventilation |

Hemodynamic instability |

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax |

Large and symptomatic iatrogenic pneumothorax |

Large, recurrent, or persistent primary spontaneous pneumothorax |

Secondary to chest trauma |

2. Hemothorax/hemopneumothorax |

3. Complicated parapneumonic effusions/empyema |

4. Malignant pleural effusion |

5. Persistent or recurrent symptomatic pleural effusions |

6. Pleurodesis for symptomatic persistent effusions, usually malignant |

7. Intrapleural thrombolytic therapy for complicated parapneumonic effusion/hemorrhagic effusions |

8. Bronchopleural fistula |

9. Chylothorax |

10. Pleural effusion secondary to esophageal rupture |

11. Postoperative care (after coronary bypass surgery, thoracotomy, or lobectomy) |

The usual argument against the use of chest tubes for pleural space infection was the high incidence of loculation within the pleural space that usually impairs chest tube drainage and prevents complete evacuation of the pleural space. However, with image-guided SBCCs, this argument may not stand anymore. SBCCs offer many advantages over the traditional chest tubes for the management of pleural space infection. First, in case of loculated pleural effusion, SBCCs can be accurately placed exactly in the desired fluid pocket. Second, in the presence of multiple loculations, several SBCCs can be placed in the same setting. Finally, in the case of numerous loculations, the use of intrapleural thrombolytic agents might be useful to break the loculation and improve the drainage.

It is unclear how the growing availability of new management options for pleural drainage has affected clinical practice in the community at large.

Malignant Pleural Effusions

Malignant pleural effusions (MPE) develop in patients with a variety of malignancies with lung and breast carcinomas and lymphomas accounting for about 70 % of all malignant effusions. Several management options exist for patients with MPEs and depend on how symptomatic the patient is, the rate of fluid reaccumulation, the presence of trapped lung, patient’s prognosis, and anticipated tumor response to the available treatment. Asymptomatic patients with slowly reaccumulating pleural effusions may benefit from repeated thoracentesis. However, for a patient in whom the pleural effusions reaccumulate rapidly, this option might be bothersome. In such patients, insertion of SBCC serves several purposes. It helps to completely drain the effusions, which is important to assess the lung expansion and to rule out lung entrapment that will affect the decision for further long-term management plans. If lung entrapment is ruled out, then pleurodesis is an effective method for long-term control of the effusion. Conventional large-bore chest tubes (24–32 F) have been traditionally employed in most studies involving sclerosing agents because they are thought to be less prone to obstruction by clots. However, their placement is perceived to be associated with significant discomfort. SBCCs offer similar efficacy and less pain and discomfort to the patients. Studies using SBCCs with commonly used sclerosants have reported similar success rates to large-bore chest tubes.

Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax can be classified as spontaneous or iatrogenic. Spontaneous pneumothorax can be subdivided into primary, in patients with no underlying lung disease, or secondary, which is associated with parenchymal lung disease. Traumatic pneumothorax results from chest trauma or as an iatrogenic complication of thoracentesis, transthoracic needle lung biopsy, transbronchial lung biopsy, or central venous line insertion.

The optimal size for chest tube needed for pleural aspiration in cases of pneumothorax is usually determined by the rate of air leak. In patients who are not at risk for large air leak (e.g., spontaneous and iatrogenic pneumothorax), SBCCs may be sufficient to maintain adequate air evacuation. However, patient with impending tension pneumothorax, underlying severe lung disease, receiving mechanical ventilation, or in cases of traumatic pneumothorax especially in combination with hemothorax, larger conventional chest tubes may be required for adequate evacuation of the pleural space.

Hemothorax

In general, large-bore chest tubes are the preferred approach in the management of hemothorax in the acute phase. However, after the acute phase has resolved, septation may form and prevent complete evacuation of the pleural space by the chest tube. In such conditions, SBCCs may be inserted under image guidance into the specific pockets and may avoid patients from further surgical intervention. In case where mature blood clots form, however, surgical intervention might be the only option to completely evacuate the pleural space.

SBCC Insertion

Insertion Site

With the traditional large-bore chest tubes, most clinicians insert the chest tube via an incision at the fourth or fifth intercostal space in the anterior axillary or midaxillary line where the tube then advanced blindly either apically or posteriorly depending on the underlying nature of the pleural disease. With this method, tube malposition can occur, especially in cases of loculated collections. Image-guided SBCCs overcome this problem by allowing the physician to accurately place the catheter exactly into the pleural collection (Table 58.2).

Table 58.2

SBCC insertion

Review indication and contraindication for the procedure including risk benefit ratio |

Review relevant imaging (CXR, CT scan, US imaging) |

Explain the procedure to the patient and make an informed consent |

Insure all necessary equipment are available |

Insure that the patient is monitored throughout the procedure |

Place the patient in supine or semirecumbent position with the ipsilateral arm maximally abducted or place behind the head |

Examine the ipsilateral thorax with ultrasound machine and choose and mark safe entry site |

Use full sterile barrier precautions (hand wash, sterile gown and gloves, protective eyewear, and a face mask) |

Create a large, sterile field on the patient’s skin, using sterile gauze and 2 % chlorhexidine solution |

Drape the patient, exposing only the marked area |

Apply local anesthesia |

1 % or 2 % lidocaine solution |

First, infiltrate the skin with 25-gauge needle to create a wheal at the previously marked entry site |

Use larger needle (21-gauge) to apply anesthesia to the deeper tissues including subcutaneous tissue, periosteum, and parietal pleura |

Using continuous negative suction as the needle advances, confirm entry into the pleural space when a flash of pleural fluid enters the syringe |

Inject the rest of lidocaine into the pleural space to anesthetize the parietal pleura and then withdraw the needle |

Repeat steps 12 and 13 using the introducer needle. Once in the pleural space, remove the syringe and introduce the guidewire. Direct the needle apically (for pneumothorax) or inferiorly (for pleural effusion) to guide your wire into the desired target |

Remove the needle with the guidewire in place (remember: never let go the guidewire) |

Make a small (0.5 cm) incision at the entry site |

Introduce serial dilators over the guidewire to dilate the subcutaneous tissue and the parietal pleura |

Introduce the SBCC over the guidewire. Insure proper placement by aspirating fluid or air through the SBCC |

Connect the SBCC to the drainage system, secure it to the skin, and place proper dressing on |

Obtain CXR to confirm placement |

A thorough examination of the chest with an appropriate imaging modality (usually US) is first performed. In cases of free-flowing effusion, the entry site is preferred to be as lateral as possible to avoid patient discomfort and tube dislodgement when the patient lies supine. In addition, the entry site is preferred to be as inferior as possible and then advanced posteriorly to the most gravity-dependant region of the pleural space to allow for maximum drainage. Insertion of catheters medial to the scapula is discouraged unless absolutely necessary because it carries the risk of catheter dislodgement with scapula movement. However, in cases of loculated collections, the entry site should be marked exactly at the site of the collection (preferably at the inferior border of the collection) seen on the US. In cases of pneumothorax, the entry site is usually chosen in the anterior chest wall, usually in the second intercostal space.

Types of SBCC

Many SBCC kits are commercially available. When choosing an SBCC kit, several things should be considered. The catheter should be made of soft and flexible material to allow for easy navigation and placement through the intercostal space and to minimize pain and discomfort to the patients. Catheters with coiled ends (pigtail configuration) are preferred for prolonged drainage of pleural effusion (e.g., malignant effusions and parapneumonic effusions) as they provide an additional locking mechanism that minimizes the chance of catheter dislodgement (Fig. 58.2). The catheter should be radiopaque, so it can be easily identified on chest radiographs. Finally, catheters should have sufficient side holes to allow for adequate drainage and minimize catheter blockage.

In general, most of SBCCs used for pleural effusions are inserted with the Seldinger technique. However, for small pneumothoraces with small air leak, a compact, one-piece pneumothorax drainage system is available (Tru-Close Thoracic Vent. UreSil, Skokie, IL). This unit is composed of a 12- or 13-French, 10-cm-long catheter connected to a rectangular chamber that contains a self-sealing aspiration port, a red signal diaphragm indicating entry into the pleural space, and a flutter valve (Fig.58.5).

Fig. 58.5

Tru-close thoracic vent. UreSil, Skokie, IL

As most of the currently available kits fulfill all of the above criteria, one should choose the kit that he is most comfortable with. Using multiple kits usually cause confusion and may prolong procedure time especially in cases of emergencies.

Preparation

Prior to SBCC placement, all available imaging should be carefully reviewed. This allows the operator to have an idea about the pleural space anatomy and the expected size and location of the pleural collection. In addition, one should insure presence of enough pleural space for a safe insertion of the catheter using the Seldinger technique without injuring the lung parenchyma.

Patient is then placed in the desired position which varies among clinicians. However, most interventionists prefer to place the patient in the supine position with the ipsilateral arm over the head. Sometimes, a lateral decubitus position is necessary to gain access to a posteromedial fluid collection. In patients with a collapsed lung with pleural effusion or pneumothorax, this positioning usually entails placing the patient with the healthy lung down. This can lead to hypoventilation in the normal lung and potentially dangerous hypoxemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree