SMA and Visceral Artery Stenting

Hari Ramachandran Kumar

Mark K. Eskandari

Indications

All patients with symptomatic chronic mesenteric ischemia should undergo revascularization. The classic symptoms include weight loss, abdominal pain, and development of dietary strategies to avoid the onset of pain (“food fear”). The pain usually develops 30 minutes after eating and can last for several hours. Constant, unrelenting pain is a concern for acute ischemia and bowel infarction. The underlying pathology is failure of adequate intestinal perfusion upon increased postprandial demand for blood flow. Typically, significant stenosis of two out of the three mesenteric vessels is needed to produce symptoms. However, isolated lesions, especially of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), can be symptomatic as well.

The differential diagnosis is extensive and patients often have undergone numerous tests over a long period of time prior to arriving at the diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia. A workup to rule out a gastrointestinal malignancy is required as the symptoms of abdominal pain and weight loss can overlap between cancer and chronic mesenteric ischemia.

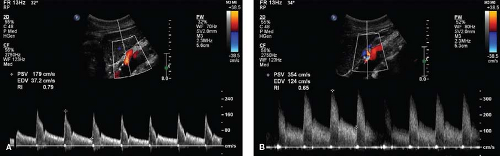

Initial evaluation of patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia should consist of a mesenteric duplex. This noninvasive test not only serves as a good screening tool but also establishes a baseline for future comparison. The duplex is performed in the vascular lab with the patient in the fasting state. The waveform of the celiac artery is normally a low-resistance pattern with continuous forward flow (Fig. 36.1A,B). The waveform of the SMA in the fasting state is normally a triphasic, high-resistance pattern (Fig. 36.2A,B).

Prospectively validated criteria for a 70% or greater angiographic stenosis include a peak systolic velocity of 200 cm/s for the celiac artery and 275 cm/s for the SMA; end diastolic velocities of 55 cm/s for the celiac artery and 45 cm/s for the SMA correspond to a 50% stenosis. Reversal of flow in the common hepatic artery is also a marker of severe stenosis at the origin of the celiac artery. While there are advantages to use of

duplex including the avoidance of radiation and contrast dye, there are limitations including restricted availability, technician-variability, or inadequate visualization with bowel gas or large body habitus.

duplex including the avoidance of radiation and contrast dye, there are limitations including restricted availability, technician-variability, or inadequate visualization with bowel gas or large body habitus.

If the duplex screening is positive, additional imaging is needed. A CT angiogram (CTA) is the ideal test to confirm the diagnosis and assess the anatomic details necessary for future operative planning. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be helpful in identifying offending lesions, but is limited in adequately characterizing the extent of aortoiliac disease as sources of inflow for a planned operative intervention. A catheter-based angiogram can also be performed but requires the operator to be prepared for a simultaneous intervention if needed.

If diagnostic testing reveals significant occlusive disease of the mesenteric vessels and the patient is symptomatic, revascularization should be performed. Intervention is aimed at relieving abdominal pain, improving nutritional status, and preventing bowel infarction. There are no effective medical treatments for chronic mesenteric ischemia and, without intervention, the downward spiral will continue.

Contraindications

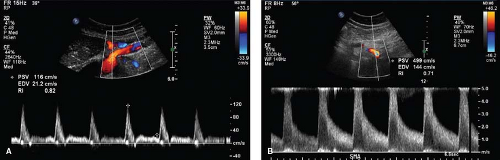

Certain lesions are not amenable to endovascular repair (Fig. 36.3A,B). Anatomic limitations of the mesenteric vessel include flush occlusion at the vessel origin with the aorta, bulky lesions, circumferential calcification, and long-segment stenosis. Anatomic

limitations of the aorta include extensive mural thrombus. Patients with refractory lesions after previous endovascular repair should be favored for open repair as well.

limitations of the aorta include extensive mural thrombus. Patients with refractory lesions after previous endovascular repair should be favored for open repair as well.

Patients who present with concern for nonviable bowel are not routinely candidates for a percutaneous endovascular revascularization. These patients require a laparotomy to assess for possible intestinal infarction and the need for bowel resection. Concurrent with the laparotomy, consideration can be given to mesenteric revascularization. Descriptions of open procedures (Chapter 11, Visceral Aortic Endarterectomy and Chapter 12, Antegrade Aorto-SMA and Celiac Artery Bypass) are located elsewhere in this book.

The procedure may be performed under general anesthesia or monitored sedation. Movement of the diaphragm during the procedure can significantly impair proper visualization. Therefore, if patients are to be under monitored sedation, they must be able to participate in breath-holds and be willing to remain supine for an extended period of time. Otherwise, general anesthesia should be used.

A thorough history and physical should be obtained. In particular, the quality of the radial, femoral, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis pulses should be documented bilaterally prior to intervention. Systolic blood pressures in both arms should be recorded as well. Laboratory testing of kidney function is mandatory.

Patients with an allergy to iodinated contrast dye should be pretreated with a regimen of steroids and antihistamines. Patients with marginal kidney function (serum creatinine 1.4 to 2.0 mg/dL) who will be receiving standard contrast agents should be pretreated with oral N-acetyl cysteine and IV fluid hydration with sodium bicarbonate. If the patient is taking metformin, this should be held for 48 hours prior to the procedure.

Prior to intervention, the patient should be initiated on dual antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin (81 to 325 mg/day) should be started at least 1 week before the procedure and taken through the morning of surgery. Clopidogrel may be started 1 week before the procedure (75 mg/day) or a loading dose may be given the day of the procedure (300 to 600 mg).

Choice of Approach

The visceral arteries can be approached in an antegrade fashion through the left brachial artery or in a retrograde fashion through the common femoral arteries. Anatomic constraints such as iliofemoral or subclavian occlusive disease, aneurysmal disease, or tortuosity should be taken into consideration when considering the choice of access vessels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree