Singultus

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

• Singultus, more commonly known as hiccups, is a pervasive problem affecting almost everyone in his or her lifetime.

• Hiccups spare no population and have been observed in human beings from preterm infants to adults.

• Hiccups appear to serve no particular function and may be remnants of a primitive reflex. In utero hiccups may be a programmed isometric contraction of the inspiratory muscles.

• Singultus is derived from the Latin singult, meaning “a gasp.”

• A hiccup is an involuntary and intermittent contraction or spasm of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles.

• Hiccups are divided into three categories, classified by the duration of the episodes.

Hiccup bouts are acute episodes that terminate within 48 hours.

Hiccup bouts are acute episodes that terminate within 48 hours.

Hiccups lasting >48 hours but <1 month are identified as persistent hiccups.

Hiccups lasting >48 hours but <1 month are identified as persistent hiccups.

Those afflicted with hiccups for >1 month are identified as having intractable hiccups.

Those afflicted with hiccups for >1 month are identified as having intractable hiccups.

• Transient hiccups tend to occur at night.

• Although the majority of hiccups are benign, chronic hiccups may portend more ominous pathology, such as infection or structural abnormalities.

ETIOLOGY

• Benign transient hiccups are believed to arise from such common occurrences as gastric distention from overeating or aerophagia, tobacco use, sudden excitement or stress, or sudden changes in environmental or internal temperatures.

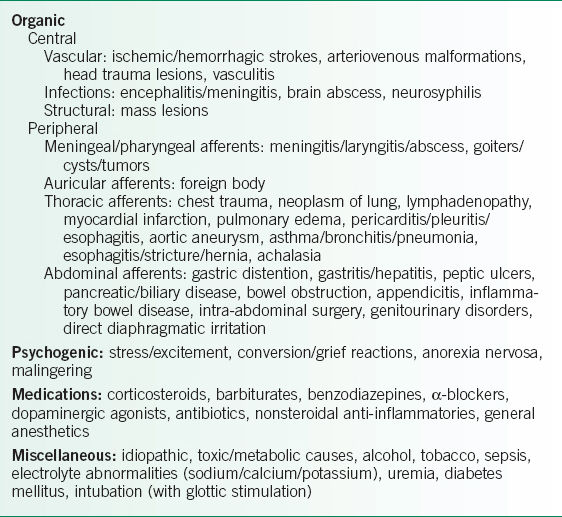

• Chronic hiccups are often pathologic in nature and can be broadly classified into organic, psychogenic, medication-induced, and miscellaneous origins.

Central processes include any disruption of the brainstem or midbrain areas.

Central processes include any disruption of the brainstem or midbrain areas.

Peripheral nervous system etiologies include those that irritate the vagus or phrenic nerves anywhere along their courses, including their cranial (vagus), cervical, thoracic, or abdominal portions.

Peripheral nervous system etiologies include those that irritate the vagus or phrenic nerves anywhere along their courses, including their cranial (vagus), cervical, thoracic, or abdominal portions.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

• Hiccups are believed to result from the stimulation of a hiccup reflex arc that involves both central and peripheral components.

• The afferent limb is composed of the phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, and sympathetic chain from T6 to T12.

• The efferent limb includes multiple brainstem and midbrain areas interacting with the motor fibers of the phrenic nerve.

• Previously, it was thought that a central connection between afferent and efferent limbs existed in the spinal cord between C3 and C5.

• It is now believed that this central connection involves an interaction among the medulla oblongata and reticular formation of the brainstem, phrenic nerve nuclei, and the hypothalamus. These interactions then manifest as repetitive, involuntary contractions of intercostal and diaphragmatic muscles with glottic closure resulting in the familiar “hic” sound.

• Irritation in any component of this reflex arc may result in hiccups.

• Hiccups more commonly (in ∼80% of cases) involve unilateral contraction of the left hemidiaphragm.

• The frequency of hiccups ranges between 4 and 60 per minute.

• Increased frequency is noted with decreased PaCO2.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

• The onset, severity, and duration of hiccups are useful details. For example, hiccups occurring during sleep often point to an organic rather than a psychogenic cause.

• A careful review of systems allows further assessment of the clinical impact of hiccups.

• Chronic persistent hiccups have been associated with such complications as malnutrition, fatigue, dehydration, cardiac arrhythmias, and insomnia.

• Social history also provides helpful diagnostic clues, as excessive alcohol and tobacco use can cause hiccups.

• Medications need to be discussed, as a number of medicines are known to precipitate hiccups (Table 7-1).1,2

Physical Examination

• A thorough examination of the head and neck should be performed to evaluate for masses, foreign bodies, or evidence of infection—all of which may be culprits in inducing hiccups.

• Lymphadenopathy may cause compression of neural structures and merit more intensive investigation for underlying pathologies.

• Given the extensive number of thoracic causes of hiccups, the chest examination is crucial to identifying the underlying diagnosis and can shed light on underlying processes such as pneumonia or asthma.

• The physical examination should also include a careful neurologic assessment because strokes and various neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis can often manifest with hiccups.3

Diagnostic Testing

• No single laboratory study can diagnose hiccups. However, based on suspected etiologies from the history and physical examination, specific laboratory studies may be helpful.

• Specific tests such as serum alcohol or electrolyte levels can exclude metabolic and toxic causes of persistent hiccups.

• The CXR and/or chest CT can be helpful for ruling out cardiac, pulmonary, and mediastinal sources of peripheral nerve irritation.

• More specialized tests such as electroencephalogram (EEG), MRI, lumbar puncture (LP), bronchoscopy, and endoscopy may be performed based on clinical findings/necessity.3

TREATMENT

• Few controlled trials have been conducted to guide the approach to hiccup therapy.

• The literature consists primarily of case reports and series that do not directly compare treatment options.

• Nonetheless, when persistent hiccups adversely affect a patient’s quality of life, treatment is indicated.

TABLE 7-1 CAUSES OF HICCUPS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree