Several recent investigations have highlighted a potential link between vitamin D deficiency and increased heart disease. Observational studies suggest cardioprotective benefits related to supplementation, but randomized trials remain to be conducted. This report adds a caution based on a statistical paradox that is rarely mentioned in formal medical training or in common medical journals. Insight into this phenomenon, termed Simpson’s paradox, may prevent clinicians from drawing faulty conclusions about vitamin D deficiency and heart disease.

Vitamin D deficiency may be a common and correctable contributor to heart disease. Alternatively, vitamin D supplements may be unduly hyped and deflect attention away from more appropriate medical care. Experts disagree, yet the basic observation remains tantalizing, namely, that patients with low vitamin D levels have more heart disease than patients with high vitamin D levels. Those versed in statistics will immediately recognize that this debate resembles past analyses involving Simpson’s paradox, a phenomenon reminiscent of the famous Will Rogers anecdote that asserts, “A person might move from Oklahoma to California and increase the average intelligence in both states.”

Simpson’s paradox occurs when a statistical finding appears in an aggregate analysis yet disappears (or reverses) in all subgroups. A classic example involves allegations of discrimination laid against the University of Berkeley for sexist admission practices. In 1973, the aggregate data indicated that women were less likely than men to gain admission to graduate schools. Individual departments, however, were generally slanted in favor of female applicants. The misleading aggregate statistic was entirely explained by a tendency for women to apply to small departments (e.g., linguistics) and men to apply to large departments (e.g., engineering). In essence, an aggregate analysis based on all applicants yielded misleading conclusions about rejection rates.

The current debate surrounding vitamin D and heart disease similarly provides a timely reminder and caution against Simpson’s paradox. This statistical anomaly is rarely mentioned in medical training and may remain unknown to most clinicians who wonder about the link between dietary supplements and chronic disease. Avoiding Simpson’s paradox usually requires a combination of medical expertise and statistical application; hence, the concept needs to be understood by clinicians who read medical research. The purpose of this editorial is to review Simpson’s paradox by highlighting a hypothetical example of how it may lead to faulty conclusions about vitamin D deficiency and heart disease.

Vitamin D Deficiency and Heart Disease

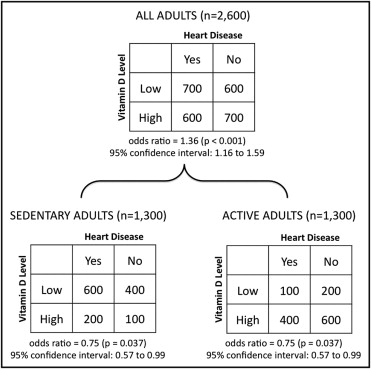

Consider the following hypothetical data of a cohort of adults (n = 2,600; Figure 1 ) . On the basis of the aggregate analysis alone, vitamin D deficiency appears to be associated with a significant increase in heart disease risk (54% vs 46%, p <0.001), corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.36 (95% confidence interval 1.16 to 1.59). Without accounting for the patient’s activity levels, clinicians may mistakenly conclude that low vitamin D levels are associated with increased heart disease in individual patients.

Consider if the patients are further stratified by activity level, with half being sedentary and the other half being active. Among the sedentary patients (n = 1,300), the baseline heart disease risk is 62%. Surprisingly, low levels of vitamin D are now associated with a decrease in heart disease risk (60% vs 66%, p = 0.037), corresponding to an odds ratio of 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.99). The data for the active patients (n = 1,300) are similar, albeit with a smaller baseline risk for heart disease (38%). Low levels of vitamin D are also associated with a significant decrease in heart disease risk in these active patients (33% vs 40%, p = 0.037), yielding an identical odds ratio of 0.75 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.99).

Simpson’s paradox arises when analyses of 2 subgroups of patients yield a contrary result compared to the aggregate analysis of when the subgroups are combined. In this case, the association between low levels of vitamin D and heart disease reversed at the subgroup level and the deficiency appeared to be protective rather than hazardous. Sedentary patients with low levels of vitamin D and active patients with high levels of vitamin D both constituted the majorities in their respective subgroups and therefore made larger contributions to the analysis when statistics were calculated for all patients combined. The paradox is compelling because the sedentary and the active patients each showed the same significant association between predictor and outcome. The aggregate data, therefore, are not valid for predicting heart disease risk for individual patients in either subgroup.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree