Chapter 51 Silicosis and Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis

Sources of Exposure

The most common form of crystalline silica is quartz. Quartz is almost pure silicone dioxide but often contains traces of other elements. Other crystalline forms of silica are cristobalite and tridymite. The importance of silica as a health hazard is due to its ubiquity (Table 51-1). Diatomite is a siliceous sedimentary rock used for filtration; for heat and sound insulation; as an adsorbent and filtering agent; as a filler material in plastics, paper, and insecticides; and in the manufacture of floor coverings.

Table 51-1 Major Industries Associated With Silica Exposure

| Occupation | Exposure |

|---|---|

| Sand blaster | Ship building, oil rig maintenance, preparing steel for painting |

| Miner | Surface coal mining, roof bolting, shot firing, drilling, tunneling |

| Miller | Silica flour |

| Glass maker | Polishing with sand and enamel work |

| Potter cleaner | Crushing flint and fettling, foundry work, mold making and vitreous enameling, manufacture of cultured quartz crystal |

| Quarry and stone worker | Cutting of slate, sandstone, and granite |

| Abrasive worker | Inhalation of fine particles during grinding |

Pathophysiology

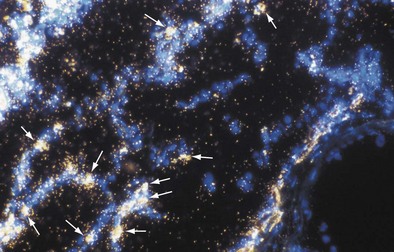

The inflammatory phase is followed by a reparative phase, in which growth factors stimulate the recruitment and proliferation of mesenchymal cells and regulate neovascularization and reepithelialization of injured tissues. During this phase, abnormal or possibly uncontrolled reparative mechanisms may result in the development of fibrosis. Fibrogenic particles activate proinflammatory cytokine production within the respiratory tract. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α seems to play a key role in the recruitment of inflammatory cells induced by toxic dusts (Figure 51-1). In addition, neutrophils recruited in the area of inflammation may contribute to the alveolitis, and respiratory and endothelial cells may play a further role by releasing various chemokines such as interleukin (IL)-8. Finally, growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and transforming growth factor-β are involved in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis and in the proliferative response of type II epithelial cells, which occurs in progressive massive fibrosis (PMF).

Histopathologic Changes

The pleural surfaces of a coal worker’s lung show an irregular pattern of bluish-black pigmentation that corresponds to the junction sites of septal-lymphatic vessels and the pleura. Peribronchial, hilar, and paratracheal lymph nodes are enlarged, black, and firm. The initial lesions in the lung are the coal dust macules, which correspond macroscopically to focal areas of black pigmentation. On microscopic examination, the macule is seen to be composed of coal dust–laden macrophages within the walls of the respiratory bronchioles and adjacent alveoli (Figure 51-2). Focal emphysema around the coal dust macule is common and is considered an integral part of the lesion of simple CWP.

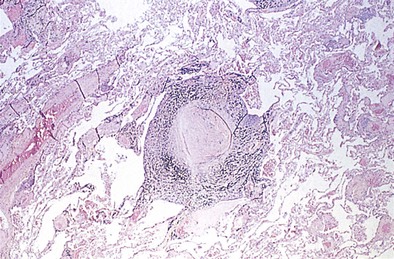

The histopathologic hallmark of simple CWP is the nodule. The nodules are rounded lesions with collagenous centers. On microscopic examination, the nodule can be divided into three zones: a central zone composed of whorls of dense, hyalinized fibrous tissue; a middle zone made up of concentrically arranged collagen fibers (onion-skinning); and a peripheral zone of more randomly oriented collagen fibers mixed with dust-laden macrophages and lymphoid cells (Figure 51-3). “Old” inactive nodules often are relatively acellular. Particles of silica may be demonstrated in the nodules as birefringent particles under polarized light. Nodules represent a form of mixed-dust fibrosis (i.e., coal dust plus silica exposure), usually are found in association with macules, and in some instances may develop from preexisting macules. They are not confined to the respiratory bronchioles but also are seen in the subpleural and peribronchial connective tissues. Nodules tend to cluster and eventually coalesce to produce PMF. Degenerative changes commonly are observed in the nodular lesions, including calcification, cholesterol clefts, and cavitation. In severe silicosis, structural alterations of the pulmonary vasculature may result from the accumulation of dust in the adventitia of large vessels, and involvement of the smaller blood vessels by silicotic nodules also may be seen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree