CHAPTER 14 Aileen M. Ferrick, RN, PhD Decision making is part of the fabric of human existence. Some decisions are less complicated and meaningful in life than others. Each of us has to make innumerable decisions per day in our personal lives. However, when it comes to health issues and unfamiliar choices, making a decision can become stressful and demanding. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a growing epidemic, with almost 3 million patients in the United States experiencing AF, and the prevalence is expected to double by the year 2050.1–3 Increasing numbers of patients are facing a decision related to AF treatment options. Their decision is 2-fold: managing arrhythmia symptoms and consideration for stroke prevention. The evolutionary advancement of ablation therapy has expanded the choices for treatment of AF with more healthcare providers referring their patients to cardiac electrophysiologists. The introduction of new oral anticoagulation therapy and nonpharmacologic approaches for stroke prevention has made decision making even more complex. The concept of patient decision making has evolved over the last several decades. The era of physicians, in the best interest of their patients, solely making decisions for their medical care has fallen out of favor. In the current age of readily available information and increased consumerism, patients and their caregivers want to be informed of all treatment options before making a decision. In fact, it has become a patient’s right to be informed before a treatment option is executed. For the most part, patients with their significant others want to make their decision for treatment in partnership with their physician using a shared approach. AF recurrence rates are high despite medication and ablation therapies, which are not necessarily curative. Therefore, the patient–physician relationship in reference to decision making for treatment of AF may be lifelong. There are many models to guide our understanding of the patient decision-making process. Many factors, including personal beliefs, patient values and preferences, as well as cultural, social, and interpersonal variables all contribute to the decision-making process. In this chapter, the concept of decision making will be explored within the context of patients making a decision for treatment of AF. Additionally, the use of decision aids and educational materials will be evaluated for their effectiveness within this process. There are a number of models guiding decision making. For example, Janis and Mann4 described a decision-making model where a proposed choice for making a decision creates conflict. Weighing the risks and benefits of the choices leads to uncertainty, which generates stress. Stress contributes to coping strategies that lead to decision making that is either maladaptive or adaptive. Maladaptive decision making is classified as procrastination, buckpassing, and hypervigilance, described as not researching options and making a hasty decision. Adaptive decision making occurs with diligent research and thoughtful consideration of options, leading to less decisional regret. Pierce and Hicks’5 interactive model of decision making, designed for patient decision making, considers specific patient factors that add to the conflict of weighing risks and benefits of alternative choices when making a decision. There are three categories. The first category is the decision problem. That includes consideration of alternative choices, complexity of each choice, probability of outcomes, and the consequences of outcomes related to each choice. The second category relates to factors of the individual patient. They include values, personal preferences, expectations, the physical and psychological states of the patient, the individual patient’s perception of risk, and their preferred type of decision-making strategy. The third component is the context in which the decision is made. This includes the patient–physician interaction, cognitive demands, environmental stressors, time frame, and urgency for a decision—and finally knowledge, and more importantly understanding, of the information being presented. The Ottawa Decision-Making Model was developed to guide patients and physicians into a shared decision-making process. Decisional conflict is a result of a state of uncertainty occurring when a patient is presented with more than one treatment option. Uncertainties when considering risk, loss, regret, and challenge to personal values leads to conflict.6 Extrapolating from Janis and Mann,4 conflict leads to stress and impacts the type of decision-making implemented by the patient as adaptive or maladaptive. The Ottawa Decision-Making Model proposes a resolution, which is to allow patients and their physicians to exchange information in an interactive forum during the decision-making process. Patient values and preferences and the physician’s scientific knowledge in regard to the choices should be discussed. Using an appropriate decision aid allows patients to comfortably acquire increased knowledge, not just in regard to their condition and AF treatment choices, but also for the shared decision-making process. If expectations of that process are met, patients can be satisfied with their final shared decision, and decisional regret is minimized. The decision-making process experienced by patients with AF is complex. Understanding factors related to the patient, the decision problem, and the context in which the problem is decided and how they may influence patients’ decision for AF treatment might be helpful for patient centered care during their decision-making process. Patient factors such as marital and socioeconomic status, age, gender, race, level of education, and employment status may individually or collectively contribute to decisional conflict and stress impacting their strategy for decision making and the resultant decision. For example, unemployment may deter a patient from undergoing ablation because of the cost associated with the procedure. Physical states, including symptoms and comorbid conditions are additional factors associated with making a choice. The frequency and duration of AF symptoms, although a physical factor, may affect patients psychologically by reducing their quality of life. Significant evidence shows that AF patients experience decreased quality of life.7–11 AF ablation may be viewed with the potential to provide a significant reduction or elimination of AF episodes and improve quality of life,12–14 whereas side effects are associated with medication therapy, and may be perceived as reducing quality of life. As such, it is the patients’ preference that must be taken into account for choice of treatment only after the benefits and consequences of each form of therapy are discussed. Although there are no studies to date regarding treatment of AF and decision making, in a study determining factors related to delay in seeking treatment for patients experiencing myocardial infarction (MI), Dracup and Moser15 determined that specific sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities could be contributing factors to the decision of when to seek medical treatment. In addition to demographic characteristics, Lefler and Bondy16 found that symptomatology and psychosocial factors contributed to the decision for seeking medical treatment for MI. Therefore, individual patient factors might influence patient decision-making preference for AF treatment as well. The decision for a specific treatment is determined within the context of the patient’s decision-making environment. The patient’s relationship to the physician who is recommending treatment choices and the information provided about alternative choices are contextual factors for patient decision making. Environmental stressors related to work, finances, and home might exacerbate decisional conflict and stress, and affect decision making. Patient knowledge of medical information provided in reference to AF and treatments, as well as the patients’ perception of the benefits and potential risks and complications of the different options, impact choice. Other contextual factors are lack of knowledge in regard to medication effects and side effects, as well as the complexity of undergoing a procedure and the probability of potential outcomes, both short- and long-terms. Patient understanding of this information, not just the exchange of information, is a factor for choice. As symptoms escalate, patients may feel time-pressured for symptom relief that may influence decision. Neglecting to personally research and deliberate all offered treatment options can lead to hastily deciding without cooperating in shared decision making with their physician. In summary, decision-making models have suggested that patient decision making requires a problem that needs to be managed with a decision, typically a decision for treatment of a medical condition. Multiple options for solving the problem need to be presented to and considered by an individual, which may create conflict. The conflict causes stress and impacts the patient’s behavior during the decision-making process. Individual factors related to the patient, the problem, and the context in which the decision is made all interact. That leads to increased decisional conflict and increased stress that may impact both the decision-making process and the strategies used to cope with making a final decision. The concept of shared decision making has not been clearly defined in the literature. To better understand shared decision making, a description of the general concepts of different types of decision making is warranted. Reason17 defines decision making as a cognitive process leading to the selection of a course of action among alternatives. A final choice, called a decision, is produced from every decision-making process. The concept of decision making is complicated, yet exercised in every aspect of daily life. Patient decision making related to health issues can be particularly complex. A lack of knowledge and understanding by the patient concerning their medical condition, and the uncertainty of outcomes from different treatment choices with resulting consequences, contribute to the complexity of the decision. Pierce and Hicks,5 in their interactive model for patient decision making, describe a decision as follows: “a decision worthy of explication has at least four basic elements: initial options (also called alternatives or choices), values (worth, utility, or attractiveness), uncertainties (or probabilities) and possible consequences (or outcomes).” The first element encompasses the treatment choices and alternatives for management of AF presented by the physician as realistic options based on scientific evidence and the patient’s overall condition. The second element of a decision is values, described as the subjective worth or attractiveness of the options to the individual patient. The third element for a decision is uncertainties or probability. Probability reflects the need for the patient to understand the consequences of each option, and evaluate the likelihood of a positive outcome occurring. Bekker et al.18 completed a systematic review of informed medical patient decision making. They determined that factors associated with patient decision making could be grouped into three categories. The first category is decision context and includes: (1) type of decision; (2) seriousness of the outcome related to the decision; (3) familiarity with the subject requiring a decision; (4) level of certainty related to the outcome of the decision; (5) the health domain in which the decision is being made (e.g., surgery or medicine) and; (6) the recipient of the decision, whether choosing for oneself or for a significant other. The second category is related to the decision maker or patient. This includes the individual’s preferred patient decision-making style as well as individual personality traits and characteristics that could potentially influence the person making a decision. The researchers explain that factors included in these two categories are not directly alterable. These reflect the complexity of the decision problem, the personal values of the individual decision maker, the risks and benefits related to the decision and the time frame for making that decision. The third category, other influences, includes the individuals’ cognitive ability for knowing and managing the knowledge shared for the patient decision-making process. Bekker et al.18 believe this factor may be managed by the relationship the individual has with their physician and the quality of the information provided to the patient in the form of a decision aid for making their decision. Charles, Gafni, and Whelan19 reviewed different styles of decision making in an effort to define a theoretical framework that would incorporate characteristics of different decision-making styles into a decision-making process (Table 14.1). Their goal was to devise a model that would have practical clinical application. They define paternalistic decision-making style as the physician solely deciding an individual’s course of treatment after considering their patient’s best interests. The patient is essentially removed from the decision-making process. The rationale for paternalistic decision making includes: (1) there are a limited number of treatment options for most conditions; (2) the physician has the knowledge and expertise to make decisions; and (3) physicians’ professional concern for their patients’ welfare legitimizes their interest in making a good decision for treatment. In recent years, paternalism has lost favor as a style of decision making. With the advent of the Internet, transparency, and patient rights, patients have become more interested in researching medical decision options and now have a greater opportunity to do so.20 An assumption related to paternalism is that there is only one form of treatment for a given condition for a specific individual. We now know that there is a balance between risk and benefit within treatment options. Therefore, patients may wish to contribute their own acquired knowledge and understanding to participate in deciding options for treatment with their physician. With advancement of medical science, there are more options for treating AF and, therefore, greater complexity in choosing the best option. Paternalism is not consistent with this changing paradigm.

Shared Decision Making for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Patient Preferences and Decision Aids

INTRODUCTION

PATIENT DECISION-MAKING MODELS

TYPES OF DECISION MAKING

Type | Knowledge of Scientific Evidence | Patient Preferences | Decision Maker |

Paternalism | Physician | Not considered | Physician |

Interpretive | Physician | Considered by physician only | Physician |

Informed | Physician and patient | Considered by patient only | Patient |

Shared | Physician and patient | Considered by physician and patient | Physician and patient |

Source: Adapted from Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1999:44(5);681–692.

Charles, Gafni, and Whelan19 describe interpretative decision making as recognizing that patient values and personal preferences, need to be considered in the decision-making process. Using interpretive decision making, the physician takes into account their understanding of the patients’ values and preferences, but still solely decide the patient’s course of treatment. A criticism of interpretative decision making is that physicians cannot feasibly interpret all their patients’ values and preferences in the process of deciding for each individual patient under their care.

Alternatively, informed or consumerist decision making was derived because of the imbalance of information the patient has compared to his physician in regard to a condition that offers multiple treatment options. The idea is to have the evidence-based knowledge of risks and benefits of a given treatment provided to the patient by the physician. The patient has knowledge of their personal preferences. The concept of informed decision making is to allow the patient to independently make a decision regarding treatment. The decision occurs only after the healthcare provider avails to the patient all relevant information related to treatment options and alternatives. The criticism for this model is that lines of communication go from physician to patient in the form of scientific knowledge only and not vice versa. Therefore, a preference that the physician may feel is best for the patient is not communicated to the patient. This concept came from the philosophy of patient autonomy where information empowers the patient to make his own choice for treatment. In its most extreme form, informative patient decision making occurs after patients are presented with decision aids.

SHARED DECISION MAKING

One-sided decision making, whether it comes solely from the patient or the physician, is not optimal. A middle ground style of decision making is shared decision making, which allows the patient and physician together to make decisions about treatment.21,22 Charles, Gafni, and Whelan19 define four characteristics for shared decision making. The first is that two parties are involved, typically, the patient and the physician. However, if the patient is elderly or the condition is serious and potentially life threatening, there may be more than the patient involved in the process, such as a family member or caregiver. If there is more than one other person, a group entity, usually specific roles emerge including an information gatherer, a coach, an advisor, a negotiator and a caretaker. There may also be more than one physician offering suggestions on treatment options. For example, with AF treatment there can be the opinion of the medical internist as well as the cardiologist and the cardiac electrophysiologist.

A second attribute is that both parties are willing and able to participate in the decision-making process. There are patients who will profess that they would prefer to have the physician make the decision for them. That may be the case, but the physician should be willing to explore the possibility that the patient is capable and should be sharing in the decision. Because of a perceived lack of knowledge, the patient may express their desire not to participate in a shared decision-making process. Decision aids can play a role in this case. If the patient understands the choices based on risk and benefits, they may come around to wanting to be a part of the decision-making process for their treatment. The physician should provide an atmosphere that is conducive to making the patient want to be part of the decision-making process. Patients must be comfortable with knowing that their values and needs can be expressed and are valued in the shared decision-making process. Both parties must be complementary in their roles for doing what is right and best for the individual patient. The result may be that the patient is satisfied with the outcome of his/her decision, and has no decisional regret. Alternatively, if the physician does not concur with the concept of a shared process, then shared decision making will not occur.

The third requisite is that each party share information. That is, the physician should inform the patient of the risks and benefits of all treatment options that would be available to the individual patient. On the other hand, the patient needs to inform the physician of information he has learned about treatment options from other resources, such as the Internet, other healthcare providers, or friends, or relatives who have experience with AF. In the interest of time, the physician must use his/her expertise to narrow down the treatment options offered to a particular patient based on scientific guidelines and the value preferences that the patient has expressed as important to him/her when sharing information with their physician.

The final characteristic of shared decision making is that there is mutual agreement on the treatment choice. Shared decision making leads to a final, shared decision. This does not necessarily mean that the physician is 100% in favor of the final decision made. Both the physician and the patient must endorse the plan as the one to implement. It is important that there is a mutual acceptance of the final decision. For a consummated, shared decision, there has to be a 2-way transfer of information between the doctor and the patient, deliberation on the choices shared between the patient, the physician, and significant others that have been expressed as important to the patient in the decision-making process, and finally, a plan for implementing the choice of treatment.

Entwistle and Watt23 elaborate further on shared decision making by defining 6 activities associated with the shared decision-making process: (1) recognition and clarification of a problem; (2) identification of potential solutions; (3) appraisal of potential solutions; (4) selection of a course of action; (5) implementation of the chosen course of action; and (6) evaluation of the adopted solution. They further establish that 2-way communication between the physician and the patient is essential to the process. The interactive process by the patient and the physician involves effective evaluation and communication throughout the shared decision-making process. Feelings about relationships to one another, and individual roles in this shared decision-making process must be communicated. Efforts in contributing to shared decision making must be conveyed by the patient and the physician to each other to be successful.

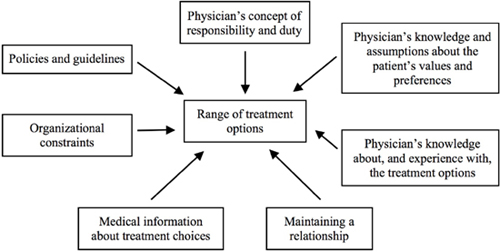

Wirtz, Cribb, and Barber24 suggest that there are a number of factors that contribute to the presentation of options by the physician in a shared decision-making experience. They include published, evidence-based guidelines recommended by professional organizations based on current scientific evidence. Cost may be a consideration for offered treatment options mandated by the treating institution’s system guidelines. Provider participation in research projects that then may be suggested as an option for treatment to the patient is an influencing factor of shared decision making. Other factors outlined (Figure 14.1)24 include physician’s knowledge of treatment options, organizational constraints (perhaps the treatment option is not offered at the practicing physician’s institution, such as a cardiac arrhythmia ablation procedure), the physician’s knowledge of the patient’s values and preferences, how well the patient–physician interaction has been maintained (if the relationship is one of trust and confidence, the message conveyed, whether emphasizing gains or losses, may influence the patient in determining choice of treatment) and the physician’s ethical concept of duty and responsibility toward the patient.

Factors influencing range of treatment options offered. Source: From Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient-doctor decision-making about treatment within the consultation—a critical analysis of models. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:116–124.

Shared decision making for AF treatment has been studied in the context of antithrombotic therapy. No studies have been found to date on shared decision making for choosing a treatment for AF as, for example, rate versus rhythm control and medication versus ablation therapy. Although there are no studies evaluating a shared decision-making style for AF treatment, studies in other populations may offer insight into shared decision making as it may relate to patients with AF.25

Murray et al.26 conducted a clinical patient decision-making survey of a random sampling of the general population through telephone interviews. Shared decision making proved to be the preferred style for patient–physician interaction (62%) compared with consumerist/informed (28%) or paternalism (9%) for medical decisions. Furthermore, they determined that those preferring shared decision-making style were in a higher socioeconomic status, earning $50,000 or more annually, and reported a close relationship to their healthcare provider, whom they rated as excellent or good. African Americans with lower socioeconomic status preferred paternalism. Those in a higher socioeconomic status and who experience a close relationship to their physician were independently associated with experiencing their preferred style of clinical decision making. Therefore, the decision for choice of therapy to treat AF, another medical condition, may be best accomplished as collaborative between the patient with AF and their physician, but future studies must be completed to draw this conclusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree