Chapter 11

Service planning and delivery for chronic adult breathlessness

Siân Williams1 and Chiara De Poli2

1London Respiratory Network, NHS London Strategic Clinical Networks, London, UK. 2London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Correspondence: Siân Williams, 30 Uplands Road, London, N8 9NL, UK. E-mail: sian.health@gmail.com

The diagnosis and management of the symptom and underlying causes of chronic breathlessness challenge current health service organisation and delivery, as evidenced by late diagnosis or misdiagnosis, underuse of effective treatments and resource waste in times of health service austerity. A new approach that builds on the evidence and experience of managing complexity in healthcare is needed. This chapter summarises where we are now in terms of the scope and scale of the problem and offers some options to tackle it. It describes how to improve diagnosis and treatment in all settings by using a decision support tool derived from multidisciplinary case-based discussion and the literature on heart failure, COPD, asthma, obesity and anxiety interventions. It also describes how to set up specific cardiorespiratory services, and how to extend the learning from the best palliative care services for breathless patients. For the longer term, it offers the vision of a population-based approach, describing aims, objectives and criteria to evaluate the impact of a breathlessness system.

It sounded an excellent plan, no doubt, and very neatly and simply arranged. The only difficulty was, she had not the smallest idea how to set about it.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland.

Why is a chapter on planning for breathlessness services necessary? After all, primary care physicians and respiratory specialists see and treat breathless patients every day. The simple answer is that the way current services are organised and delivered is unsatisfactory, and they do not provide value for the patient, the population or healthcare systems.

First, breathlessness is a problem with a high degree of complexity [1]. Chronic breathlessness has a gradual onset, leading to unpredictable presentation to health services, and may have multiple possible causes, which may be interrelated. The interactions between its causes create uncertainty in diagnosis, often requiring more than one consultation and multispecialist engagement. Research lags behind practice needs, formulaic approaches and disease-specific clinical guidelines have only a limited role, and healthcare professional expertise may not be enough.

Secondly, breathlessness illustrates the substantial challenges to traditional health and care services of the increasing prevalence of people with multimorbidities. For example, only 18% of patients diagnosed with COPD have only COPD [2, 3], and by the time a patient with COPD and disabling daily breathlessness presents to a GP, they may have up to 13 other symptoms [4]. Health and care services that are not equipped to cope with this complexity have unintended consequences in terms of late diagnosis and misdiagnosis, under- and overtreatment, and waste. These compromise outcomes, some of which increase inequity [5] and all of which are costly and probably unaffordable in times of financial and health service austerity [6, 7].

Thirdly, there is a problem of scale. Breathless patients are frequent users of primary, secondary and emergency services, and this also has implications for care coordination.

This chapter argues that planning services for a breathless population presents real opportunities to create an innovative and sustainable response to 21st-century healthcare complexity. Aimed at clinicians, health service planners and policy makers, the chapter is organised into three parts. The first two sections summarise the complexity of breathlessness and why the current services fail to deal with this complexity. The next section then describes how ideal care for breathless patients would look. In the third part, three options for improving how breathlessness is assessed, managed and treated are discussed. The first option, which could be used in the short term, suggests the adoption of the IMPRESS (IMProving and Integrating RESpiratory Services in the NHS) decision support tool for the assessment of breathlessness. The tool has been designed to be used in a range of settings. In the medium term, specific breathlessness services could be developed, along the lines of those being set up in the English NHS (e.g. the Breathlessness Intervention Service in Cambridge, and cardiorespiratory assessment clinics). The ultimate option would be a population-based breathlessness system, where multiple providers, payers and health professionals work with patients to coordinate efforts and pool resources and knowledge in order to improve outcomes for a breathless population. The chapter concludes with five guiding principles for any stakeholders involved in designing, planning and implementing breathlessness services, together with some questions for reflection and review of local data for continuing professional development.

Chronic breathlessness is a complex and common problem

Chronic breathlessness is a common symptom, affecting up to 10% of adults [8, 9], and about 60% of older people experience some degree of breathlessness [10]. It is the feeling associated with impaired breathing, a subjective [11] and often frightening experience that may limit all aspects of life and can be associated with poor clinical outcomes [12, 13].

Patients use an array of terms to describe their breathing sensation, and the term breathlessness can represent a number of qualitatively distinct sensations [14–17]. These different sensations will depend on personally felt interactions between physiological, psychological, social and environmental factors [11]. Breathlessness can also be described by the individual in terms of time course, frequency and triggers [18], its intensity and the distress it evokes [19–21], its impact on function, and psychological and social well-being [22]. Qualitative studies on the experience of breathlessness show that the range of descriptors used by patients varies across the underlying conditions causing their breathlessness [16, 23–25].

There is no single test to objectively and conclusively diagnose its root cause or multiple causes. For the tests available, cut-off points can be controversial, and the several measures to assess it are not validated against each other. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, developed by the cardiovascular community, is a functional classification that includes breathlessness, among other symptoms. The Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale is also a functional classification, focusing exclusively on breathlessness, and is used by the respiratory community. The wording of this scale has altered over time, with consequences for clinical practice, as grade 3 in some pathways is the threshold for referral to pulmonary rehabilitation.

Breathlessness can be caused by a single underlying condition, or by the interaction of two or more underlying conditions (e.g. COPD, heart failure, anaemia, asthma and/or obesity). Two-thirds of the cases of breathlessness receive a cardiac or respiratory diagnosis [10, 26–28], and about 20–30% of cases receive more than one diagnosis [26, 28].

The diagnosis of breathlessness must take into account the individual’s mental and psychological health, because their emotional reaction to their sense of breathlessness intensifies the perception of breathlessness [29]. It should also be contextualised with respect to their demographic characteristics and physical activity levels [30, 31]. It is a common symptom among older people and those in the last year of life because of the accumulation of long-term conditions [32]. It can be caused by obesity or tobacco dependence, which can partially explain why it is often underreported by patients who silently adapt to its limitations by doing less, assuming that it is part of the ageing process [33, 34], or attribute it to being overweight or generally unfit [35] or to smoking.

The subjective nature of the symptom, its potential multiple causes (physical, mental and behavioural), the lack of a single and objective test or measure to assess it, and the unpredictable reporting by patients can each explain why diagnosing breathlessness can be difficult [26, 28]. In some cases, the diagnosis or contribution of various components to the person’s breathlessness remains uncertain, if not unexplained [36].

There is no consensus on the optimal pathway for the diagnosis of chronic breathlessness, or on how best to organise and deliver breathlessness services. Currently, experiences available in the English context represent local clinician-led improvements rather than whole-system changes [37].

Unsurprisingly in such a patchy context, breathlessness is often mis-, under- or overdiagnosed. Causes such as COPD, heart failure and anxiety are all underdiagnosed in primary care [38–40] and are often diagnosed late, sometimes after a first hospital admission, and therefore are suboptimally treated. Similarly, obesity is identified and referred inadequately [26, 28, 41]. These failures in diagnosis can result in poor-quality and therefore poor-value care, with increased costs, waste and harm to the person [42].

Where are the problems today?

Traditional health and care systems are not equipped for dealing with these complexities. Poor outcomes are almost inevitable and can be explained by a number of interrelated problems.

A first order of problems relates to how healthcare services are organised and delivered. Breathlessness triggers many primary care consultations [43–46], although the number of reported cases of breathlessness are substantially lower than expected from epidemiological studies. This mismatch between expected and reported data can be explained by a combination of poor or inconsistent coding practices by physicians and equivocal patient help-seeking behaviour. Acute episodes of breathlessness are a major cause of ambulance call-outs, hospital attendance and emergency admission [47–49], putting a great strain on hospital beds already under increasing pressure given the growing prevalence of long-term conditions and their exacerbations. However, routine analysis of admissions by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10 will miss this. Given the paucity of data, there has been little analysis of the impact of breathlessness on service use, despite its prevalence.

Similarly, little is known about the impact of chronic breathlessness on patient outcomes, which can be substantial. For example, in people living with COPD, their comorbid psychological difficulties are frequently associated with poorer outcomes (e.g. rates of exacerbation, hospitalisation and readmission, length of stay and treatment adherence, self-management and survival rates after emergency treatment) than people without psychological comorbidities [50–52].

The traditional organisation and delivery of services for patients reporting breathlessness does not facilitate a comprehensive assessment and a coordinated treatment of breathlessness and its underlying causes. Time-limited primary care consultations and distorted reimbursement systems can affect the assessment and diagnostic process. In primary care, there may be a tendency to attach a diagnosis to the symptom of breathlessness as soon as possible without allowing time to build a diagnosis. This has clear consequences on how breathlessness, the patient’s reason for the encounter, is coded, but also affects the patient’s adherence to a treatment plan [53, 54]. In addition, the approach to diagnosing, treating and managing breathlessness is not uniform across respiratory and cardiology specialist services. Moreover, the evidence suggests that patients who do not fall neatly into an organ-based specialty remit may become lost in the system or neglected [55–57]. Poor coordination of care between primary and secondary care, and between health and social care, can adversely affect a patient’s outcome and increase waste [58, 59]. Lack of clinician confidence in behaviour change skills may also contribute to the problems of “hand-offs” to other services [41, 60].

When looking at management and treatment options for people with heart failure, COPD, asthma and, to some extent, obesity [61, 62], there is a substantial underuse of high-value interventions. It is likely that these interventions will be high-value interventions for breathlessness. They include: 1) flu vaccination and pneumococcal vaccination, which are cost-effective for COPD, heart failure and asthma and yet vaccination rates remain low [61, 63–67]; 2) smoking cessation [61, 68]: the prevalence of tobacco dependence in people with COPD, asthma, pulmonary fibrosis and heart failure is often higher than the average prevalence [69–74] and yet opportunities are not taken to help smokers quit in primary care or on admission [75–77]; 3) programmed rehabilitation programmes for people with COPD, heart failure or both, which have been shown to be cost-effective [78] and there are no safety reasons to exclude patients with heart failure except those with arrhythmias [79, 80], yet evidence suggests that there are insufficient pulmonary rehabilitation programmes for people with COPD, and that there is an even greater lack of cardiac rehabilitation programmes accessible to people with heart failure [81–84]; 4) physical activity [85], which reduces the risk of the underlying causes of breathlessness and yet lack of assessment of physical activity or active patient engagement remains a major challenge [31, 86]; 5) self-management and personal care planning [87, 88], which can be effective but are not widely used, and there is little evidence yet on the effectiveness in multimorbidity [89]; and 6) psychological and emotional support, for which there is a limited but growing evidence base of value in improving adherence to care plans, as well as reducing the impact that breathlessness has on the person’s life, yet this is not routinely available as part of multidisciplinary teams to support the team and patients [90].

A second order of problems relates to the limited availability of evidence that can be meaningfully used in day-to-day clinical practice by health professionals faced with an ageing population and a growing prevalence of multimorbidity. Specifically, there seem to be three main interrelated issues: 1) the evidence that is generated by researchers; 2) what evidence-based guidelines are produced; and 3) how the evidence available informs clinical practice and service planning and delivery.

There are substantial blind spots in the literature with respect to both the epidemiology and the clinical management of breathlessness. Cost-effectiveness analyses are typically organised by diagnosis, and hence none is available for breathlessness. There is also a substantial deficit of research delivered by allied health professionals, such as physiotherapists, psychologists and dieticians, whose experience is underrepresented in the literature [41].

Evidence-based guidelines are usually organised around single diseases and conditions although people increasingly have more than one [91], are based on trials that exclude people with comorbidities [3], and ignore the fact that people present with symptoms that may have a number of root causes and that they often have both physical and mental health needs. By focusing on optimal treatments following diagnosis of a single disease, they may be of limited use for day-to-day clinical practice, especially in primary care. The fact that we observe wide variations in clinical practice confirms the struggle of practising evidence-based medicine [92].

Unsurprisingly, a by-product of disease-specific evidence-based guidelines has been the specialisation of medicine, with chronic disease management increasingly being provided within disease-specific clinics, to the detriment of generalist services in primary care or outpatient departments, which would be best placed to offer holistic, patient-centred and coordinated care [93].

The pitfalls of traditional evidence-based medicine in the current demographic context have been recognised, and an agenda for “real evidence-based medicine” [92] has already been put forward. In this framework, health professionals may use the best evidence available complemented by their intuition, experience, collective or tacit knowledge (“mindlines” [94]), which is probably more able to manage uncertainty and complexity. This framework also suggests that evidence about “know-what (works)” ought to be supplemented with “know-about” (e.g. comorbidity, psychological status, the local population), “know-why (e.g. the historical explanation of behaviours)”, “know-how” (to translate and tailor the general evidence into patient-centred care personalised for the specific case) and “know-who” (to involve the correct people to implement it successfully) [95].

What are we aiming for?

As the previous section has described, traditional health and care systems are not equipped for dealing with the complexity of chronic breathlessness in adults. Care and services currently offered to patients with breathlessness are generating poor health outcomes and seem unaffordable, and therefore are providing low value.

An ideal service for adults with chronic breathlessness would aim to improve health outcomes and be cost-effective, financially viable and context specific. Such a service would encompass a triple aim: 1) to minimise the impact of the symptom and its underlying cause or causes on the person’s life; 2) to use available resources in the optimal way, prioritising interventions with high value for the individual and for the population, reducing waste (e.g. avoiding repeat diagnostic tests or multiple appointments, and tackling avoidable hospitalisation and readmissions [96, 97]) and making every contact count [98]; and 3) to be sustainable over time and institutionalised within different settings with the necessary capacity provided by a trained and motivated workforce; the ultimate goal of a sustainable service is the continued achievement of desired population health outcomes [99], e.g. by reducing the incidence or severity of breathlessness and by reducing premature mortality associated with breathlessness. Thus, the overall aim would be to minimise the impact of adult chronic breathlessness within available resources and in a sustainable way.

The design and implementation of a breathlessness service needs to be highly context specific, depending on demography, local capacity (e.g. primary care, secondary care, palliative care) and leadership (e.g. a primary care physician with an overarching view or special interest, or a respiratory–cardiology team, or an integrated care physician), the role of the payer and available resources, and how the service sits in the broader care system.

In order to take account of these contextual factors, a gradual and incremental approach to designing, planning and implementing services or interventions for breathlessness is recommended.

In the short run, a decision support tool for the assessment of breathlessness, such as the one developed by IMPRESS, could be used by any health professional dealing with a patient presenting with breathlessness. A further or additional development in the medium term might be the development of a breathlessness assessment and treatment service for people with difficult-to-manage breathlessness, which could lead to the creation, in the long run, of a breathlessness system.

How can we get there in the short term? A decision support tool

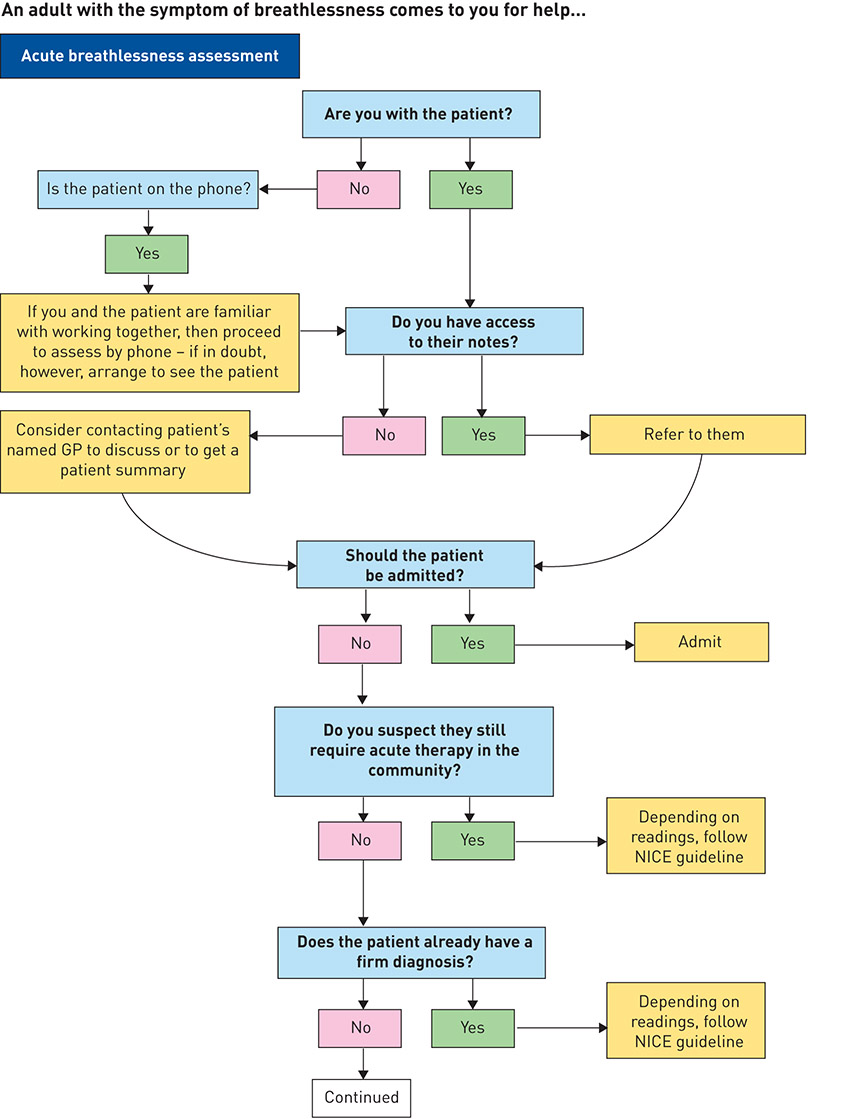

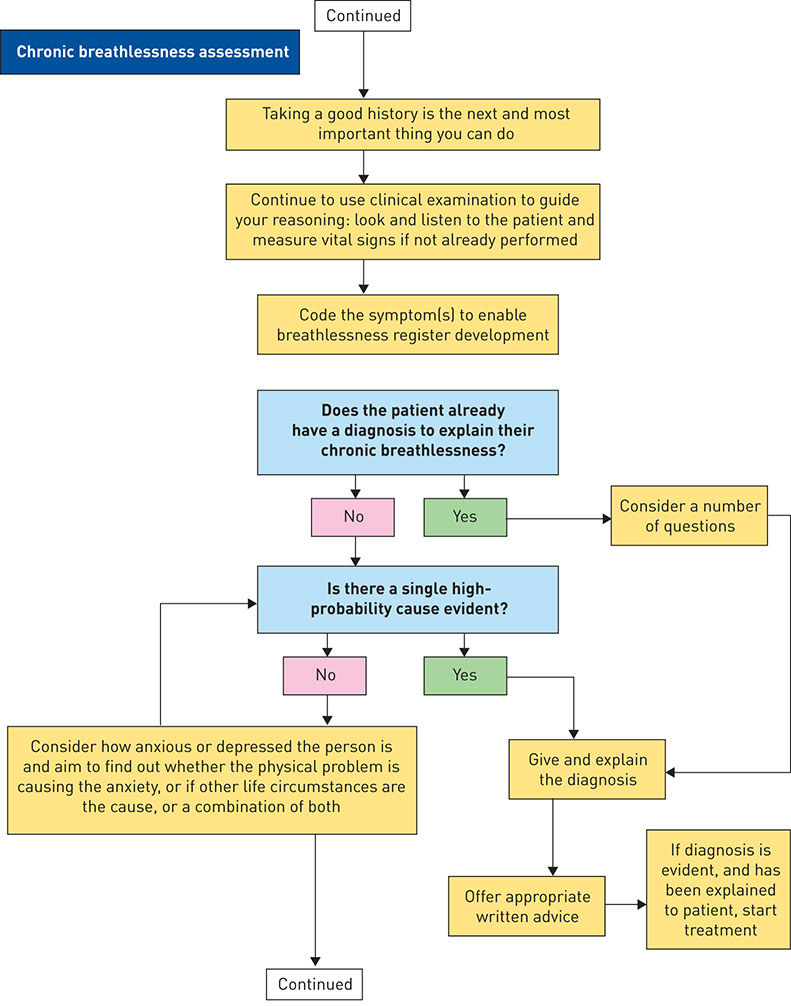

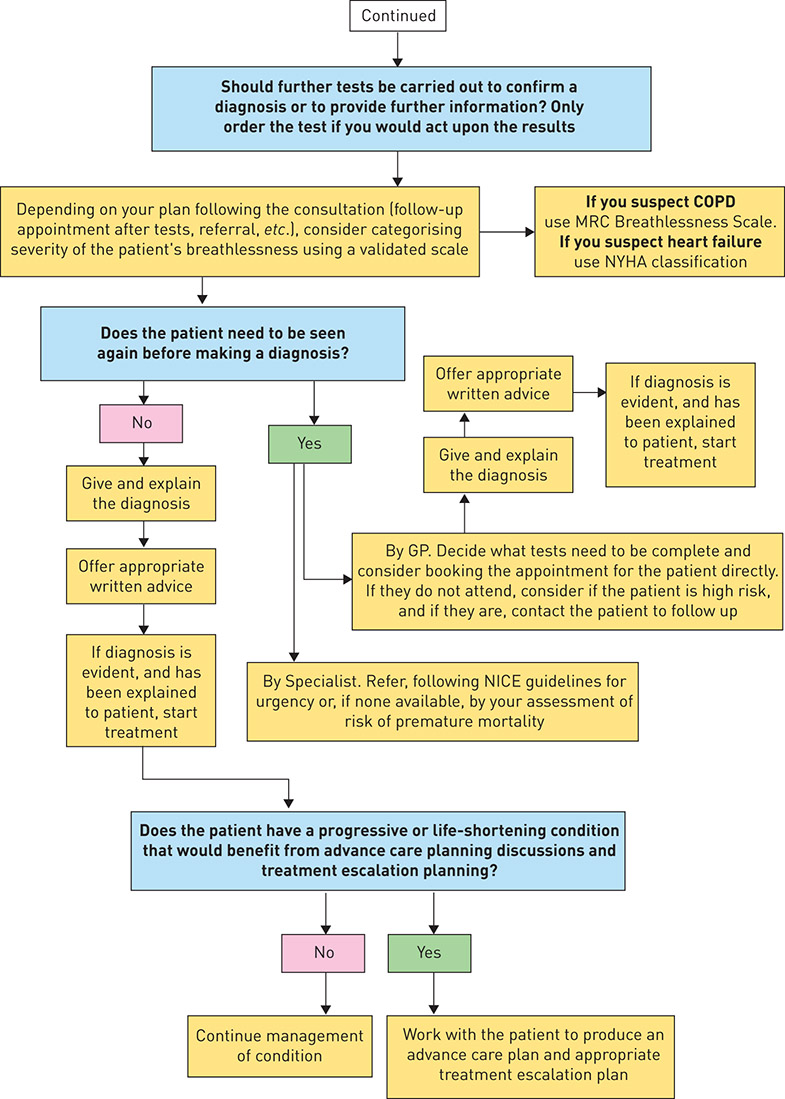

In 2013, IMPRESS, a joint initiative of the British Thoracic Society and the Primary Care Respiratory Society UK, two leading professional societies for respiratory care in the UK, developed a decision support tool for the assessment of breathlessness (figure 1).

Figure 1. IMProving and Integrating RESpiratory Services in the NHS (IMPRESS) breathlessness algorithm. NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; MRC: Medical Research Council; NYHA: New York Heart Association. Reproduced and modified from [100] with permission.

IMPRESS has an impressive record of achievement in working with general practice, community and hospital care, and across professions, culminating in a comprehensive assessment of the value of interventions for COPD [62, 101–103]. Building on these previous experiences and a strong base of trust among colleagues, IMPRESS invited experts with an interest in breathlessness drawn from different settings (general practice, hospital and community), specialties (respiratory, cardiology, obesity and mental health) and disciplines (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, psychology, management, academia) across England to develop the decision support tool. A comprehensive review of the literature and other publicly available policy documents was complemented by expert case-based consensus when the evidence was not available or weak.

The tool recommends an assessment process to be followed with a chronically breathless adult in primary care, or at first contact elsewhere in the system (figure 1). It acknowledges the strengths of a family physician approach, given family physicians’ training in holistic approaches, continuity and relationships of trust built over serial encounters [104]. It shows how the diagnostic process for breathlessness ought to be circular and iterative, rather than linear, in order to improve the certainty of diagnosis and treatment decisions. For experienced clinicians, it acts as a reminder of best practice, while it acts as a guide for less confident colleagues.

The guidance acknowledges that breathlessness is highly subjective and that, accordingly, the process of diagnosis ought to be individualised for each patient. The clinical decision support tool highlights the importance of good clinical judgement and acknowledges both the art and science of medical practice. The art relates to the tacit knowledge and soft skills of health professionals: their empathy in listening to patients’ histories and in examining them, and, whenever a diagnosis is made, in explaining it clearly and compassionately. The science is application of the evidence by using validated questions and questionnaires and counselling, as well as near-patient testing and prescribing.

The decision support tool recommends 15 points that the family physician or other health professional with a chronically breathless adult patient should consider. This decision support tool could be embedded into an electronic record system in general practices:

1. Manage the acute component to the patient’s condition, even where there is a pre-existing diagnosis of a chronic condition. Identify who needs admission, to be managed by the appropriate specialist team because this will improve outcomes [105, 106]. Pulse oximetry is a simple and discriminating test for respiratory failure (irrespective of the cause, which may be cardiac) and should be done first, because patients with new or worsening respiratory failure always need admission. A high respiratory rate, high pulse rate and worrying blood pressure, noting the presence of pulmonary oedema or extensive peripheral oedema, are also important and may suggest that admission is necessary. There are further reasons for admission, which may depend on knowing what is normal for that particular patient.

2. While assessment, diagnosis and treatment are normally sequential, in reality, if the patient’s breathlessness is acute, diagnosis and treatment will merge (e.g. appropriate oxygen for hypoxia), and sometimes a trial of treatment is the most appropriate next diagnostic process.

3. For patients who do not need admission, take a full history, including smoking status, physical activity and psychological status; use the history to guide clinical examination in order to exclude diagnoses. There are three validated tools to assist:

3.1. Very Brief Advice: ask all chronically breathless patients about their current and past smoking history and calculate pack-years, where appropriate, to advise and act [107, 108]. The use of a carbon monoxide monitor to objectively check smoking status can also be a useful motivational tool to help a patient quit [74, 109].

3.2. The General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) to ask about physical activity [85, 110].

3.3. Asking “What do you think causes your breathlessness?”, which can sometimes directly bring out anxiety-inducing concerns. Where mental health problems may coexist, use validated screening tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 4 (PHQ4) [111], the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD7) if anxiety seems likely [112] or the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9) if depression is likely [113]. Their value is in identifying the people who would benefit from a psychological assessment and intervention because their response to their breathlessness is creating a significant impact on their well-being and/or on health service use.

4. Ask about the impact of breathlessness on the person’s life, using a mix of open and closed questions: “How does your breathing/breathlessness make you feel?”, “Has your breathlessness been frightening to you or your family?”, “What has your breathlessness stopped you doing that you want to do again, or would like to do for the first time?” Remember omissions (what is not said) can be equally important, and observe the length of sentences that are spoken and the ease of this [114].

5. Two-thirds of breathlessness is due to cardiac or pulmonary causes [115]. Start with diagnosing/excluding common causes using evidence-based tests for asthma, COPD, heart failure, obesity and anaemia. Recognise that anxiety may also be a cause or may coexist [26, 116]. Use low-cost physical measurements, such as waist circumference, if this is manageable. The strength of the association between BMI and heart failure events declines with a person’s age, but increased waist size is a predictor of heart failure, even when measurements of BMI may fall within the normal range [117, 118].

6. Remember that, while common things do occur commonly, there may be an alternative explanation or additional explanation for the breathlessness. Patients with pulmonary or cardiac disease may not tolerate some small additional problem well, and so problems such as anaemia or infection may cause worsening breathlessness. It is better to be uncertain than to make the wrong diagnosis and have to correct it later.

7. If electronic records are being used, consider using a breathlessness symptom code (e.g. Read parent code 173 or International Classification of Primary Care RO2) until a diagnosis is confirmed, and maintain the symptom code as “active” and “significant” to encourage future review of breathlessness status and revisiting of the cause, and as a baseline measurement of performance.

8. During the primary care consultation, make sure to establish the patient’s understanding, ideas and expectations. When giving the diagnosis, address Leventhal’s five components [53]: 1) What is it? 2) How long will the problem and the treatment last? What treatment options are there? 3) What caused it? 4) What will happen now and in the future? 5) Can it be cured or controlled? The way in which the diagnosis becomes conceptualised by the patient will affect their self-management and outcomes.

9. Provide the right information tailored for the needs of the patient and/or their carers. IMPRESS has produced information for patients with breathlessness that has been well received by patients [119].

10. Test to confirm diagnosis. For example, if heart failure is a possible explanation, measure a natriuretic peptide and refer to specialist assessment, such as a rapid-access one-stop diagnostic clinic if the level is above the value that excludes heart failure. If there is a history of previous myocardial infarction, refer without measuring the level of natriuretic peptide [120].

11. Beware of assuming that previous mental health problems are the cause: death rates from physical causes, often caused by tobacco dependence, are much higher than average in people with mental health problems [121, 122].

12. Once a diagnosis is reached, provide high-value evidence-based treatments, following national guidelines where they exist. These will include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments: flu and pneumoccocal vaccination, treatment for tobacco dependence, self-management support, medication, programmed rehabilitation and physical activity [123–126].

13. Recognise the risks of iatrogenic hospital admission [127] or harm, and aim for appropriate polypharmacy [128]. Recruit effective medicine reconciliation strategies [129].

14. Be familiar with the community resources that exist to help people learn to breathe better, e.g. swimming, yoga, Pilates, tai-chi and singing in a choir [130], as well as pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation, walks and exercise classes. Personal care plans should include these options. Practice teams can be taught and engaged in population diagnosis and intervention design to improve population health [131].

15. If the patient has a progressive or life-shortening condition that would benefit from advance care planning discussions, work with the patient to produce an advance care plan and an appropriate treatment escalation plan. Specialist breathlessness clinics for people with advanced disease may also prolong survival [132].

New services to improve care for people at risk of poor outcomes

Where there is prolonged uncertainty, or the patient would benefit from multidisciplinary support, there may be a need for a new breathlessness service. This would consist of a pathway connecting the first point of contact, typically the GP, with additional multidisciplinary and integrated assessment and treatment services, with a feedback loop to the referrer to enable continuity of care. In terms of priority, decisions will be needed about where to target services to achieve the aim of minimising the impact of adult chronic breathlessness within available resources and in a sustainable way. This process may need to reallocate existing resources of clinical and patient time, tests and space (including beds) to improve the equity of access to care and of outcomes. Options that may be considered include: shared decision making; integration, including virtual clinics, administration and estates; substitution of location, skills, technology, model or organisation; segmentation of the breathlessness population; and simplification of processes [133].

The process of developing a breathlessness assessment and treatment service should build on the services or interventions currently available locally and requires data on the population at risk of poor health outcomes and of unscheduled care, including ambulance use. This is likely to include people with severe mental illness who have significant premature mortality from respiratory and heart disease [121], as well as people with complex psychological problems who would benefit from multidisciplinary support.

There may be opportunities to integrate existing teams and services. A review of inclusion criteria might enable a harmonisation of approaches between diseases, or the rethinking of referral systems and incentives. For example, more integration between heart failure and COPD services may provide more value than separate specialist services.

Increasing integration of services may also benefit from reinforcement of the natural “care coordinator” role delivered by the GP [134, 135] or by new professional roles, such as integrated care consultant posts and registrar schemes that benefit from an integrated training across settings [136, 137]. In some circumstances, there may be options for extending frontline staff capacity to deliver behavioural interventions, to “make every contact count” [138] and to ease the access to relevant tests and results.

In community settings, case management or care management can improve the delivery of clinical and social services to patients with complex needs, e.g. patients suffering from progressive, life-threatening chronic diseases that can be improved with proper treatment such as CHF and COPD, people with multiple morbidity or people at high risk with poor access to care such as homeless people, for whom supportive care can enhance independence and quality of life. For these patients, healthcare resources generally are available but may be inaccessible or poorly coordinated [58, 139–141]. Case or care managers or care navigators can help deliver care that is more seamless than routine care, for example by helping patients improve their self-management skills, identifying services that could meet their needs and facilitating access to these services, improving communication across providers, reviewing the needs of the patient over time or acting as a patient advocate. Electronic patient-held records, such as those enabled by Patients Know Best (www.patientsknowbest.com) or VitruCare (www.vitrucare.com), can also support better self-coordination of care.

In hospital settings, multidisciplinary care planning conferences held with patients and their family are also a promising approach that can be used during a hospital admission to diagnose and treat contributing causes and coordinate inputs from a range of professionals, including physical and mental health and social care. Care planning conferences aim to support the coordinated delivery of high-value interventions (e.g. treatment of tobacco dependence) started in hospital and continuing in the community, complemented by plans for risk reduction, for treatment escalation and for EOL care [142].

It is unlikely that there will be sufficient provision of programmed rehabilitation. To this aim, current provision should be reviewed, also taking into account seasonality, as adults with long-term breathlessness are a population whose health and use of services varies across the year [143, 144]. Shortages of programmed rehabilitation could be addressed by increasing the places available in cardiac rehabilitation programmes, and/or inviting people with heart failure to pulmonary rehabilitation clinics. Any increase in capacity needs to be accompanied by support for GP referrers to build their confidence in promoting programmed rehabilitation to their breathless patients.

People with a disproportionate response to their chronic breathlessness may benefit from breathing re-education [145] and psychological support, including relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapy [146–151]. The evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions is promising [90, 152]. Therefore, a breathlessness service should also provide access to allied health professionals, including physiotherapists and psychologists. A breathlessness service could also signpost to additional activities, such as swimming, yoga, Pilates, tai-chi, choirs [130], walks and exercise classes, which may be offered by local-authority or third-sector organisations.

For those patients at the EOL whose breathlessness is caused by COPD or heart failure, the breathlessness service should provide advance care planning. This offers the healthcare professional, carer and patient an opportunity to discuss sensitively the choice of place to die, without a bias in favour of one location, as sick, frightened and breathless people may choose hospital [153, 154]. A breathlessness service for patients at the EOL should also provide an active management of each symptom [153].

Looking to the longer term: creating a breathlessness system

In the longer term, a healthcare system for the population at risk of, or with, breathlessness, with a defined budget, should be the planning goal. Such a system should enable the achievement of the triple aim of minimising the impact of adult chronic breathlessness within available resources and in a sustainable way. This requires collaboration between patients and carers, stakeholders and clinical leaders from primary care, respiratory, cardiology, mental health services, psychological services and obesity services to describe their needs, to share local experience of living and dealing with breathlessness, and to review the data and evidence.

The following nine steps are recommended when developing a breathlessness system [155]:

1. Define the scope of the breathlessness system.

2. Define the population to be served, which may include subpopulations or segments at different levels of complexity and activation requiring different services [156, 157]; it may include people with complex needs, such as homeless people, who are known to many service providers, including GPs, ambulance services, EDs and respiratory departments, and who would benefit from better care coordination to improve their breathlessness [139].

3. Reach agreement on the aim and objectives of the services provided by the system, also considering options for disinvestment.

4. For each objective, agree one or more criteria by which the performance of the service would be assessed.

5. For each of the criteria, identify levels of performance that can be used as quality standards, based on the data locally available.

6. Identify all the resources used in the system, thus creating a breathlessness budget, including clinical staff, equipment, diagnostic tests, hospital beds, prescribing budgets, estates and administration.

7. Identify who needs to be engaged in a clinical network that will provide collective leadership for the system and be accountable for its performance.

8. Produce a breathlessness system specification that can be used for contractual arrangements between providers and payers.

9. Agree an evaluation framework to assess the impact of the breathlessness system

With the London Respiratory Network, the collective leadership of respiratory care in the NHS in London, UK, we tested objectives and criteria for a breathlessness system aligned to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [158] and to the aims of the Global Monitoring Framework on Non-communicable Diseases set by the World Health Organization [159]: 1) by 2030, reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being; 2) achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all; and 3) strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate [158].

We offer these as a starting point for local discussion. Standards should be agreed using local baseline data. The main objectives and criteria for a breathlessness system are outlined in table 1.

Table 1. Objectives and criteria for a breathlessness system

Proposed objectives | Suggested criteria |

Improve accuracy and timeliness of the diagnosis to enable earlier treatment | At least one putative diagnosis of the cause of breathlessness made at first assessment in primary care/alternative setting |

Proportion of breathless people who have had a comprehensive assessment, including: smoking status measured with exhaled carbon monoxide monitor where necessary; peak flow; spirometry; chest radiograph; oximetry; height; weight; waist circumference; ECG; and BNP where appropriate | |

Reduction in hospital admissions with undiagnosed COPD later confirmed by spirometry | |

Reduction in hospital admissions with undiagnosed CHF | |

Reduction in admissions or ED attendances for people with undiagnosed adult asthma | |

Proportion of breathless people who have been assessed for morbidities in addition to main diagnosis | |

Achieve a 25% relative reduction in premature mortality for patients with COPD and heart failure aged 30–70 years by 2025, and a relative reduction in asthma deaths [159] | Mean age at death with COPD |

Mean age at death with heart failure | |

Number of deaths at age <75 years in people with severe mental illness | |

Increase access to high-value interventions | Flu vaccination rate |

Prevalence of current tobacco use in people aged ≥15 years [159] | |

Prevalence of overweight (BMI ≥25 kg·m−2) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg·m−2) in people aged ≥18 years [159] | |

Physical activity (i.e. 150 min of moderate-intensity activity per week or equivalent) in people aged ≥18 years [159] | |

Proportion of breathless patients referred to rehabilitation services | |

Completion rate of rehabilitation programme | |

Availability of palliative care services for people with heart failure and COPD | |

Availability of appropriate drug treatment for tobacco dependence, COPD and heart failure | |

Proportion of people accessing weight reduction interventions for morbid obesity, including bariatric surgery as treatment for respiratory failure due to obesity | |

Improve the quality of life for people who have chronic disabling breathlessness | Increase in proportion of breathless people with written information that they can recall |

Increase in proportion of breathless people with an agreed care plan that is adjusted for their level of activation | |

Increase in proportion of breathless people screened as having anxiety who are referred for psychological assessment | |

Increase in proportion of breathless people without an underlying disease who are referred to a physiotherapist and/or psychologist for breathing technique training, relaxation and coping strategies | |

Improve the experience of dying for people who have disabling and progressive breathlessness | Increase in proportion of patients with chronic breathlessness grade 5 (or MRC 4) and those with emergency hospital admission with breathlessness and/or respiratory failure, and their families and carers, who are offered advanced care planning conversations as part of routine care by staff skilled in these conversations, including discussions about the role of ICU, NIV, safe oxygen prescribing for respiratory failure, treatments for breathlessness and EOL preferences |

Increase in proportion of people with COPD, heart failure or ILD admitted as an emergency with breathlessness with a documented advanced care plan before admission | |

Reduce waste of resources | Reduction in proportion of hospital admissions for breathless people who do not have respiratory failure |

Reduction in total annual bed days for people with COPD and heart failure | |

Reduction in number of people on triple therapy who have not been referred to pulmonary rehabilitation | |

Reduction in resource use in the year prior to diagnosis | |

Reduction in smoking-attributable bed days and admissions | |

Reduction in proportion of current smokers with new lung cancer diagnosis | |

Reduction in single outpatient appointments for patients with multiple conditions in a year | |

Increase in patients admitted with breathlessness who have had a medicine reconciliation | |

Sustain the service through robust workforce development and support, stakeholder engagement, and slowing disease progression | Increase in proportion of staff trained in Very Brief Advice |

Increase in proportion of staff trained to use and act upon a psychological screening tool, such as PHQ4 | |

Increase in proportion of staff trained to use a validated measure of physical activity and act upon the results | |

Availability of multidisciplinary training | |

Reduction in variation in the first six objectives | |

Reduction in year-on-year vacancy levels in the service | |

Reduction in smoking rates of the staff in the service | |

Increase in flu vaccination rates of staff in the service | |

Code consultations for chronic breathlessness consistently and accurately to enable the collection of real data on the size of the problem, the outcomes and the cost | Consultations coded, e.g. by using the MRC breathlessness score or appropriate national coding systems, e.g. Read parent code 173 in UK general practice |

Report annually on improvements | Annual report published |

Promote and support interdisciplinary research on chronic breathlessness | Increase in published research on the management of breathlessness involving more than one discipline or specialty |

BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; MRC: Medical Research Council; PHQ4: Patient Health Questionnaire 4. | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree