Since the initial coronary balloon angioplasty (BA) in humans by Andreas Gruntzig in 1977, significant advances have occurred in the field of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (

1). Over time, stents have become the most important mechanical technique for percutaneous interventions. The problem of restenosis after balloon angioplasty (BA) has been significantly reduced with the advent of coronary stents, as highlighted by two landmark randomized trials comparing BA alone with stenting (

2,

3). Although the vast majority of trials of coronary stenting have reported on the results of balloon-expandable stents, self-expanding stents may be important tools in the armamentarium of the interventional cardiologists.

Stents can be classified according to their basic design type (mesh, slotted tube, coil, ring, multidesign, and custom), their composition (stainless steel, nitinol, tantalum, other), or their mode of delivery (balloon-expandable, self-expanding). The purpose of this chapter is to review the clinical results when self-expanding stents are placed in the native coronary arteries and in saphenous vein bypass grafts.

THE WALLSTENT AND MAGIC WALLSTENT

The Wallstent was the first stent to undergo evaluation, with Rousseau et al. implanting 47 stents in the coronary arteries of 28 dogs (

4). Thrombotic occlusion occurred in 35% of cases in which antiplatelet agents were not administered. Neointimal formation and endothelialization of the stent occurred by the third week after implantation. In 1986, clinical evaluation of the Wallstent began with the first human implantations performed by Jacques Puel, in France (

5). By early 1988, 117 Wallstents had been implanted (94 in native coronaries and 23 in aortocoronary bypass grafts) (

6,

7).

In the early 1990s, multiple European experiences with the Wallstent were reported (

8,

9). Initial indications included restenosis in coronaries treated with prior angioplasty, stenosis of aortocoronary bypass grafts, and acute coronary occlusion secondary to intimal dissection after BA. In these early studies, stent thrombosis was a significant clinical problem, occurring in 24% of cases.

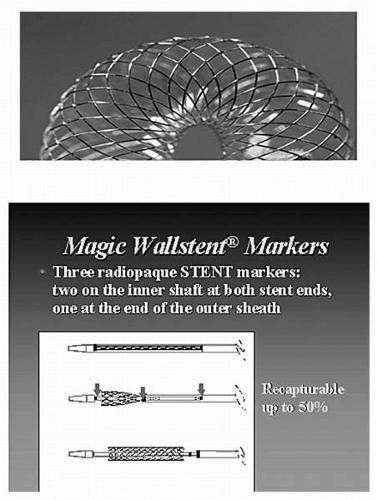

The original stainless steel Wallstent has been replaced by the Magic Wallstent, a device made of a nonferromagnetic, cobalt-based alloy with a platinum core. The wire is arranged into a self-expanding mesh that relies on the elastic range of metal deformation to expand. The metallic surface area in the newer stents was reduced from 20% to 14%. The new delivery system has an important safety mechanism: a retractable sheath that enables a partially deployed stent (up to 50%) to be recovered with the sheath and repositioned (

Fig. 37.1). This feature is of particular value because it allows the precise deployment of this self-expanding stent device. After deployment, the Wallstent continues to expand until equilibrium is achieved between the elastic constraint of the vessel wall and the dilating force of the stent. When placing the Magic Wallstent, the physician should select a stent size that is 20% larger than

the diameter of the adjacent reference segment. Details of the technical specifications and stent delivery system of the Magic Wallstent are shown in

Tables 37.1 and

37.2.

In 1996, Ozaki et al. reported their experience with the implantation of 44 new, less shortening Wallstents in the native coronary arteries of 35 patients with acute or threatened closure after BA. These investigators used a strategy of oversizing of the Wallstent diameter and complete lesion coverage (

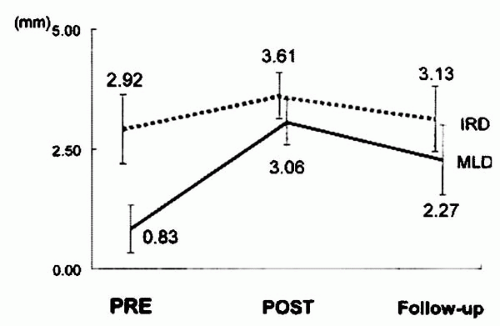

10). Stent deployment was successful in all patients. The nominal stent diameter was 1.40 mm larger than the maximal vessel diameter. One patient (3%) with a dilated but unstented lesion proximal to the stented segment sustained a subacute occlusion 1 day later, resulting in a myocardial infarction (MI). Event-free survival at 30 days was 97% (34 of 35 patients). Data on 6-month follow-up angiography are shown in

Figure 37.2. Angiographic restenosis was observed in 5 of 31 patients (16%) at 6 months, all of whom underwent repeat angioplasty. Thus, the overall event-free survival at 6-month follow-up was 83% (29 of 35 patients). Despite its small size, this study demonstrated the excellent deliverability of the Wallstent and the safety of oversizing the stent diameter compared to the reference vessel diameter.

In the Wallstent in Native Vessels (WIN) trial, 586 patients were randomized to BA or stenting using the Magic Wallstent. Clinical and angiographic results were similar at 6 months, but 37% of patients in the BA group crossed over to stenting because of suboptimal results (

Table 37.3). The efficacy of the Wallstent also was assessed in patients with vein-graft disease in the Wallstent in Saphenous Vein Grafts (WINS) trial. In WINS, 268 patients with saphenous vein graft (SVG) lesions were randomized to placement of the Wallstent or Palmaz-Schatz stent. Both in-hospital and 6-month outcomes were similar (

Table 37.4).

In a study of 162 vessels, Williams et al. assessed clinical and angiographic restenosis following the deployment of the long coronary Wallstent (

11). Forty-eight percent had an unstable coronary syndrome, and 94% had AHA grade B or C lesions. The mean lesion length was 37 ± 20 mm, and the mean stent length was 48 ± 20 mm. The procedural

success rate (defined as successful deployment of the Wallstents without procedural complications, such as no reflow) was 99%, and the primary success rate was 93% (defined as patients leaving the hospital event-free). Six patients suffered subacute stent thrombosis, the majority being in the era of anticoagulation rather than antiplatelet regimes (

Table 37.5). Clinically, event-free survival at follow-up was 73%; however, 41% had angiographic restenosis. This study showed that the Wallstent can be deployed in complex long lesions with a high primary success rate, but it is limited by the occurrence of restenosis.

In the Randomized Trial of Endoluminal Reconstruction Comparing the NIR Stent and the Wallstent in Angioplasty of Long Segment Coronary Disease (RENEW) trial, Nageh et al. compared the balloon-expandable NIR stent and the self-expanding Wallstent (

12). In this study, 82 patients (85 vessels) with long coronary lesions (>25 mm) were enrolled. Successful deployment occurred in 41 (100%) of the self-expanding stent group and 41 (93%) of the NIR

stent group. Mean lesion length was similar in the two groups (26.6 ± 6.9 mm versus 28.7 ± 9.8 mm;

p = 0.2), but the mean length of the self-expanding stent was greater than that of the NIR stent (41.6 ± 18.8 mm versus 35.4 ± 16.2 mm, respectively;

p <0.05). No significant difference was observed in the rate of major events between the two groups at 6-month follow-up (

Table 37.6). The angiographic restenosis rate was lower in the balloon-expandable stent group, but this did not reach statistical significance (26% versus 46%, respectively;

p = 0.1), and the target lesion revascularization rate was similar for both groups (7.9% versus 7.7%, respectively;

p = 0.8).

The self-expanding stents and balloon-expandable stents display different mechanical and dynamic properties. Recently, König et al. analyzed the impact of the respective stent design on coronary wall geometry using quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) and intracoronary ultrasound (IVUS) measurements (

13). They compared the Wallstent and the balloon-expandable Palmaz-Schatz stent. Serial measurements were performed within the stent and within reference segments of 50 patients (25 Wallstents, 25 Palmaz-Schatz stents). Relative changes for each parameter in both stent designs were calculated. The luminal net gain in the Wallstent group was not significantly higher compared with the Palmaz-Schatz group (1.63 ± 1.11 versus 1.44 ± 0.63 mm;

p = NS). The respective loss indexes were also similar (0.38 ± 0.42 versus 0.36 ± 0.23;

p = NS). The Wallstent segments showed significant postinterventional stent expansion with positive vessel remodeling. The respective stent design had no impact on the vessel reference segments.