Fig. 2.1

College grades for congenital heart surgeons who are now members of the CHSS (Congenital Heart Surgeons Society) or EACHS (European Association of Congenital Heart Surgeons)

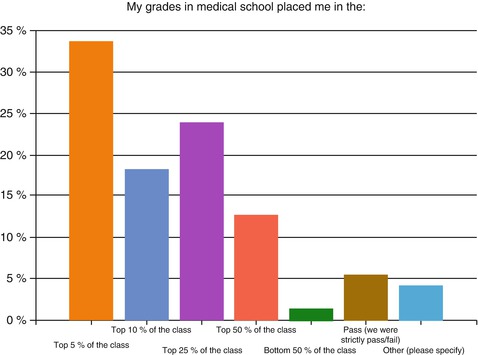

This ability to perform well academically followed them through medical school where 33.8 % were in the top 5 % of their medical school class, over half (51.2 %) were in the top 10 % of their medical school class and ¾ (76 %) were in the top 25 % of their class (Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 2.2

Medical School grades and class rank for congenital heart surgeons who are now members of the CHSS or EACHS

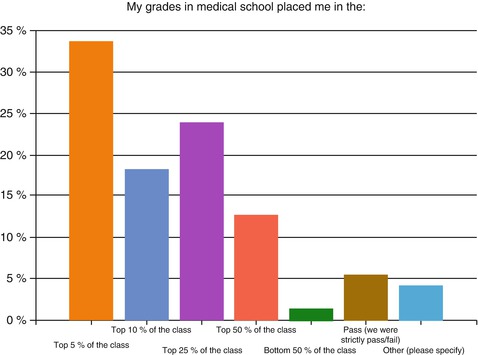

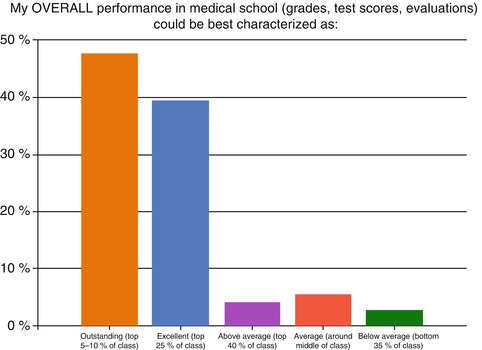

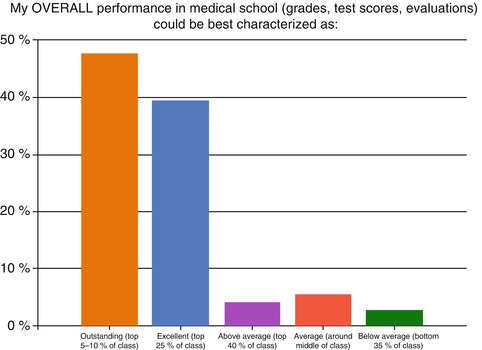

In fact, when ranking overall medical school performance (grades, recommendations, test scores), 87.3 % were considered to be excellent students (top 25 % of their medical school class) (Fig. 2.3).

Fig. 2.3

Overall performance rank in medical school for congenital heart surgeons who are now members of the CHSS or EACHS

For the most part, our responders were highly regarded and successful students through college and medical school. We suspect the same is true for those who have become experts in cardiology, anesthesiology and critical care medicine. For students trained in US medical schools, almost half of our “experts” (45.3 %) were elected to the Alpha Omega Alpha society.

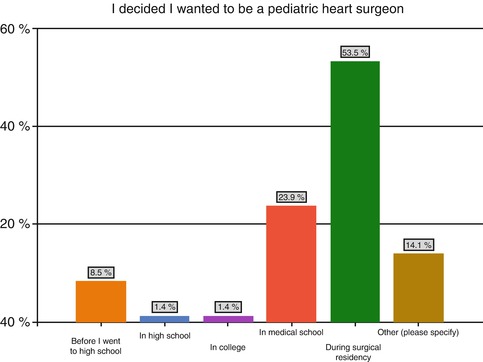

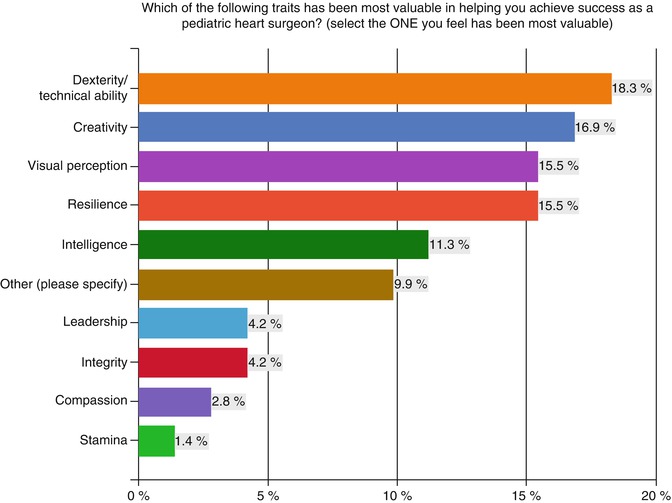

Most of the respondents to this survey had been in practice for over 11 years (84.5 %; and in fact, 40.8 % had been in practice for over 20 years). Over half of today’s pediatric cardiac surgeons (53.5 %) decided to pursue congenital heart surgery as a career while they were in their surgical residency (Fig. 2.4). With diminished exposure to cardiac surgery in today’s residency programs (Wake Forest University, for example, as is true for numerous other excellent general surgery training programs, does not have general surgery residents rotate onto cardiac surgery services) it may become less likely that surgical residents will become interested in (much less “enraptured by”) cardiac surgery. Limited exposure to cardiac surgery during residency, less contact with cardiac surgical faculty mentors who can share their excitement in cardiac surgery and a commitment to mentoring interested residents, and emphasis on the different skill sets of general versus cardiac surgery will likely diminish this previously important pool of residents who will choose to pursue careers in cardiac surgery. Only one fourth (23.9 %) of our respondents decided they wanted to be pediatric heart surgeons in medical school, with another 10 % deciding prior to attending medical school (before high school—8.5 %; in high school—1.4 %; in college—1.4 %).

Fig. 2.4

Time period when congenital heart surgeons who are now members of the CHSS or EACHS decided they wanted a career in congenital heart surgery

As the exposure to cardiac surgery becomes less available (at least in surgical residency), and exposure to pediatric cardiac surgery becomes less available during CT residency (most of those in the 14.1 % “other” category decided on pediatric cardiac surgery during their CT residency) our field may not be able to cultivate the kind of excitement and allure—rapture—that was possible in the past; unless we change our expectations of how and when we will attract (and expose) our future colleagues.

With the emergence of a variety of challenges–economic limitations for personal reimbursement; competition amongst centers which diminish individual case volumes; decreasing jobs (at this time) for some specialties like pediatric interventional cardiology and congenital heart surgery; perceived competition between pediatric and adult cardiologists as well as between cardiologists and surgeons for certain procedures; less (sometimes no) exposure to cardiac surgery in many general surgery training programs as well as limited exposure to cardiology and cardiac critical care in even some of the largest pediatric training programs; reluctance of some general surgery program directors to train individuals interested in cardiac surgery; and the lifestyle attractions of alternative career choices–it might be presumed that students in the top 20 % of their classes would not be attracted to a career in pediatric cardiac specialties, and requirements for additional training. But this doesn’t take into account the power of rapture.

Educational programs have been changing. In the US, integrated 6 year training programs (I-6) for cardiac surgeons, which not only save time over the traditional programs of general surgery followed by cardiac surgery, but also offer more exposure to cardiac and thoracic surgery to the interested residents throughout the training years [23, 24], have become extremely popular and are attracting highly successful and talented students [25]. It appears (based on our own experience) that extremely talented and exceptional students are interested in and attracted to a career in pediatric cardiac surgery, cardiology and anesthesiology/critical care medicine, despite the perceived challenges mentioned above. There are still several who select this career path later in training, so it will be valuable to maintain some traditional pathways [26].

Selection in a past era revolved around grades, academic performance and an abundance of qualified applicants. The applicant pools to the current I-6 training programs demonstrate that there are still numerous qualified applicants—in fact more than there are current spots to accommodate them [27]. The increased interest of outstanding and qualified medical students to apply for integrated training that can increase their exposure to cardiac surgery is clear [25, 27]. If these opportunities are not available to the medical school applicants, then they might be forced to enter the alternative track of general surgery training programs, which have changed considerably in their content and exposure to cardiac surgery, as well as in their attitudes towards training prospective cardiac surgeons. Although the data from our survey suggest many trainees selected cardiac surgery through their experiences while undertaking general surgery residency, the enormous changes to general surgery training, along with the lifestyle and demands of additional training may make pursuing a cardiac surgery career seem unattractive and undesirable once general surgery training begins. The integrated 6-year training programs provide a “preemptive” invitation to enter training in our field. Our options to deal with this challenge might include a more active involvement in medical school curricula, and encouragement of more programs to develop an integrated 6 year training model (as well as support from the Residency Review Committee (RRC) of the ACGME to approve and encourage development of more of these programs) [23], so that we can nurture the interest of those who choose our field by being involved with their training from the time they choose it. It is not as likely that we will be part of the types of surgical training curricula that will be inviting and enticing to residents in general surgery programs—they simply are not having the opportunities in the current programs to be exposed to, much less encouraged to consider a career in, cardiac surgery. Therefore, the previous conventional pathway through general surgery may become less optimal and conventional tracks to cardiac surgery training may disappear, particularly as avenues for the best, brightest and most highly motivated.

Given the multiple competing demands for resident’s time in pediatric training programs, even some of the most competitive programs have limited exposure to subspecialties like cardiology (to as little as a 1 month rotation over the 3 years of the training program). A choice by a student to pursue a career in pediatric cardiology or in cardiac anesthesiology/critical care requires selection to a pediatric or anesthesiology training program, followed by selection into one or more specialty training fellowships.. Recently, a combined pediatric and anesthesiology residency has been developed leading to certification in both specialties. Entry into this type of program involves early selection and may result in development of novel skill sets and permit greater exposure to pediatric cardiac and critical care [28]. Despite this novel integration of training, there are currently no integrated training programs that can “fast-track” the experience and provide increased exposure to congenital heart care to the interested trainee in these specialties. Some have argued that pediatric cardiologists may not require three full years of general pediatrics training to be an academic subspecialist cardiologist [29].

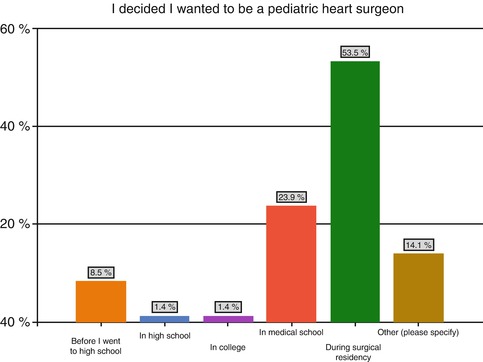

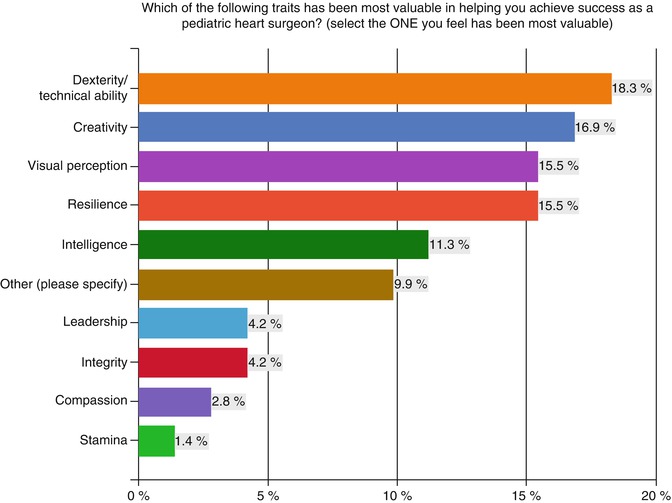

Another consideration in the selection process is the identification of the qualities that are consistent with success in the field of cardiac surgery (and these can certainly be extrapolated to all disciplines). When asked to choose from an extensive list of traits that they felt were most correlated with helping them become successful congenital heart surgeons, the following traits were chosen by more than 10 % of respondents—Dexterity/technical ability (18.3 %); Creativity (16.9 %); Resilience (15.5 %); Visual Perception (15.5 %) and Intelligence (11.3 %) (Fig. 2.5). Many in the “other” group mentioned persistence and commitment—tenacity. As we talk to program directors, many are focused on how to identify and cultivate technical ability and dexterity. We find it fascinating that, on reflection, many of today’s most successful surgeons feel that (while technical ability, dexterity and visual perception are certainly important) other traits such as resilience, creativity and tenacity are also extremely valuable. How we identify and select for these traits may be important in how we select those who will follow.

Fig. 2.5

Importance of certain traits deemed by congenital heart surgeons who are now members of the CHSS or EACHS to be valuable to success. The scale demonstrates a degree of importance with the longer bars being considered more valuable

When asked what factors were most useful in evaluating applicants for training, responses were fairly emphatic—evaluators were looking for passion (rapture), and this was often expressed (as they indicated in separate comments) by “work ethic”, resilience, perseverance, determination and motivation to be a successful contributor to the field.

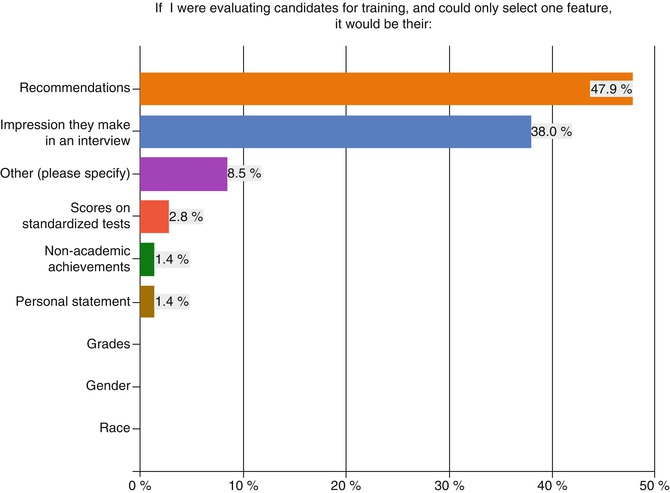

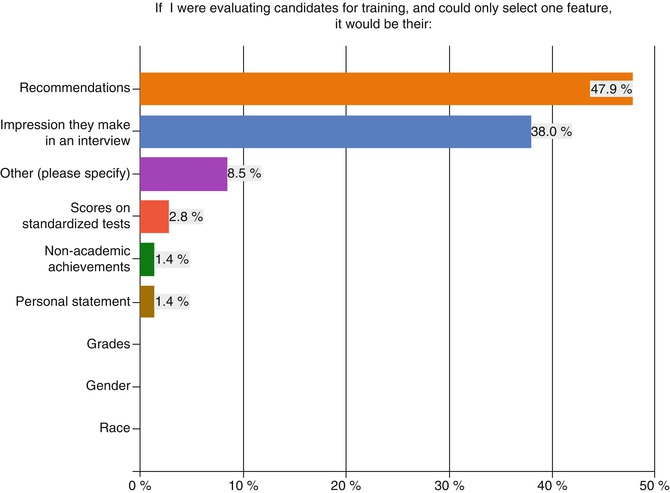

Evaluators were also looking beyond grades and standardized test scores and numerous responders indicated that they were looking for a past history of success (31 %) and outstanding personal values (29.6 %) demonstrated as: emotional intelligence, humility, honesty and ability to listen (also expressed directly as commentary). The importance of this will be discussed in the section under training, but it is clear that in choosing those we wish to train, grades and test scores are no longer adequate as a barometer. More and more experts desire that the applicant possess some cultivation of their personal growth. This is consistent with the research of Goleman [30–32], and others [17, 33–42], who have demonstrated that emotional intelligence (driven by self-awareness and self-management) correlates more with long term success than intellectual intelligence; and both are likely important and necessary to be successful in the practice of high quality pediatric cardiac surgery. Of the experts surveyed, 0 % used grades to evaluate applicants and only 2.8 % used standardized test scores to guide their selection process. Many evaluators believe that they can best assess for these additional qualities through recommendations (47.9 % of responders—and even more so if the recommendations were from people they knew and trusted—stated most frequently in the “other” responses) or by the impression that the candidate makes in an interview (38 %) (Fig. 2.6).

Fig. 2.6

Factors considered to be most valuable when evaluating future congenital heart surgeons, as indicated by surgeons who are now members of the CHSS or EACHS

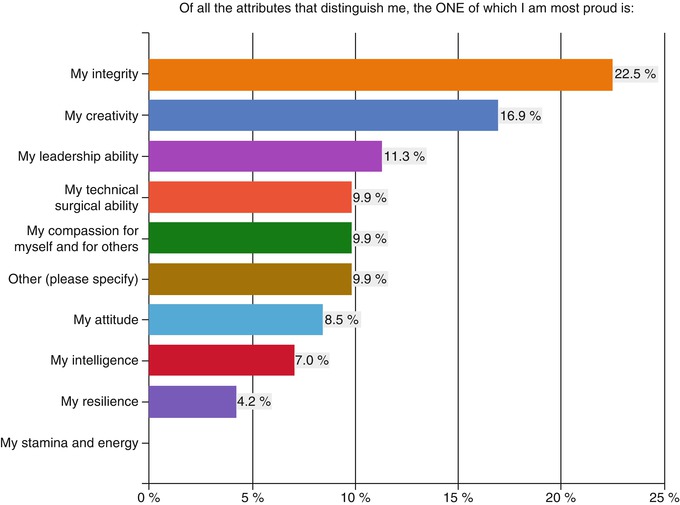

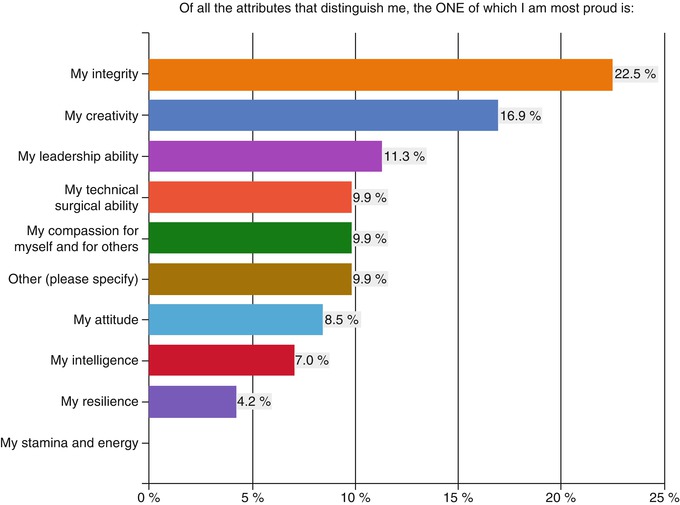

Of particular interest was that when asked which quality (from a long list) (Fig. 2.7) was the ONE that they felt most distinguished them and of which they were most proud, over half indicated their integrity (22.5 %), their creativity (16.9 %) or their leadership ability (11.3 %). No other attributes (including technical abilities or intelligence) were selected by more than 10 % of responders (although compassion for families and others was highly rated). Since these are qualities that are difficult to measure outside of an interview or a recommendation, it is not surprising that these two factors (recommendations and interviews) were rated so highly.

Fig. 2.7

Attributes considered most distinguishing of them as surgeons by members of the CHSS or EACHS. The bars demonstrate a scale of frequency, with the longer bars indicating a trait valued by the highest number of surgeons

At this time, the majority of applicants for residency training in cardiac surgery in the US are coming through the traditional track of general surgery, as opposed to an integrated 6-year (I-6) training program. Therefore the applicant pool for CT surgery is largely comprised of those who enter general surgery training as a gateway to CT training. An unintentional consequence of this is that we are left to ultimately choose from applicants who meet the criteria set forth by the general surgery programs, which often rely heavily on grades and standardized test scores. By virtue of emphasizing different selection criteria, these general surgery programs may be denying access to the types of applicants who we might find most attractive to select for training in cardiac surgery, particularly pediatric cardiac surgery. This same problem exists in many specialties. In anesthesiology, residency selection has been highly correlated with scores and grades [43]. Unfortunately, academic endeavors such as research and publication history, which may be indicative of “work ethic”, seem to have no significant influence. Thus, exceptional candidates who could possibly be outstanding contributors to our field might never have an opportunity to be selected, and they end up pursuing other career options. At least one residency program has addressed this by essentially making the interview process 24 h including meals to permit further interrogation of the “softer” qualities that may be valuable to the success of our professions.

There is another side of selection, which revolves around how we, as a profession, are “chosen.” Excellent students are still attracted to cardiac surgery (as well as to related fields in cardiac care) and want us, as educational leaders, to provide them with the kind of training programs that will help them achieve their dreams of contributing to and making our field better. With the significant changes that are occurring in general surgery residency training programs (less exposure to cardiac and thoracic surgery, diminished expressed enthusiasm for cardiac and thoracic surgery as a career option—some general surgery training programs are actually disinclined to take residents with that potential interest, and transition of training to skills that are less comparable to the ones needed for pediatric cardiac surgery in particular), we can imagine that there will be declining interest from general surgery residents to enter the field of cardiac and thoracic surgery, much less pediatric cardiac surgery. The same may likely be happening in pediatrics and in anesthesiology, where training in the field of eventual interest is not available during the initial years of internship and residency. This in part is attributable to the knowledge base and experience required to achieve proficiency in the general principles of each specialty and then the complexity of each subspecialty area further limiting exposure. Prospective candidates may simply become discouraged by the layers that precede the exposure to the training they really want, and in some cases, may choose other fields entirely.

This will be a challenge that we will confront in the future—how do we respond to a pool of potential applicants to our profession that is created by our lack of ability to provide them with exposure to the fields they are most interested in? Once an applicant chooses us, and we choose them, our attention turns to how we can best train them to become successful.

Training

Our ability to train our future has been significantly influenced by changes imposed over the past decade by the ACGME. Accredited training in all specialties is now regulated by rigid duty hour restrictions, which not only limit the number of hours that trainees can work per week, but also regulate how much time they can spend in the hospital on call and how much time they are required to be off (and out of the hospital) between shifts. Although the intent of this work hour limitation is to create a more balanced, healthy and productive health care worker; and to limit errors related to fatigue and stress, the ramifications on training have been enormous, particularly in certain fields (such as surgery or interventional cardiology) where hands-on experience is a vital component of excellence.

There are conflicting reports regarding the affect of duty hour restriction on operative volume in surgical training programs, although for the most part, surgical volumes have decreased in subspecialty training programs [44–49]. Where operative surgical volumes have been maintained, there is legitimate concern that this has been at the expense of residents sacrificing other important experiences, such as outpatient clinic evaluation [49] for preoperative evaluation or postoperative follow up of surgical patients, as well as in-hospital care of convalescing patients [50]. Nevertheless, surgical trainees report spending less time in the operating room [44], and it is not evident that there is less likelihood for medical errors since the result of the duty-hour limitation is increased transitions of care (or cross covering of care), as well as a reduced sense of “ownership” by trainees of the patients they are caring for [44]. In some settings, such as the ICU, there is a national perception of decreased patient safety [51].

Hospital systems have adapted by having much of the work that used to be time consuming delegated to other health care providers, and the multidisciplinary approach has now encouraged a more collaborative team approach for sharing in the work, with intensive care being provided by board certified intensivists (instead of by surgeons), and daily rounds being performed by cardiologists, hospitalists or care extenders (such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants). Despite the attempt to relieve the residents in training of this “extra” work, many residents feel that their training experience is reduced and negatively affected by the duty hour limitations. In national surveys of both medical and surgical residents, the vast majority report either no change or a decreased quality of education after the most recent work hour restrictions (centered on reducing duty hours for interns) were released [52]. Although designed to improve patient safety and decrease burnout, this outcome has not been a clearly demonstrated result from duty-hour limitation [44]. This in part may be related to the multiple factors, besides fatigue, that contribute to burnout such as emotional well-being, job satisfaction and a sense that the work is worthwhile, and a sense of being needed—all of which might be negatively influenced by duty hour limitations [44, 53–55].

All of this has resulted in a dilemma where some residents feel compelled to “under report” their actual hours (which results in a sacrifice of personal integrity). Alternatively, the trainee can attempt to strictly adhere to the rigid duty-hour limitations; thereby missing what might be perceived as potentially valuable experiences and occasionally upsetting faculty who they believe expect them to ignore the rules (thus creating the message that “the rules don’t apply to us”—which is a dangerous message). Faculty are not entirely without accountability and there are instances where the faculty has explicitly sent this message to the trainee, giving them little choice but to comply.

Concern over the consequences of duty hour restriction was expressed in the open-ended responses by some of our experts, such as this very pointed statement:

While it goes against current residencies, I think the “maximum exposure” by ridiculous overwork for 2 or 3 years gave me the ability, experience, and knowledge to have less bad patient outcomes in my first 5 to 7 years of practice. To become an expert, exposure is the most important thing, the less exposure the more “on the job learning” which translates to poorer patient outcomes.

Striking the ideal balance between enhancing resident education and improving patient safety will require continued efforts and creative monitoring of outcomes. Perhaps the balance will be different among various sub-specialties that require diverse skills and training. Regardless, there is extensive literature on work hours and their relationship to human performance in health care and other safety-sensitive industries and further discussion is necessary on how exactly to best apply this information to physician training programs [56–63]. Ignoring the evidence about the potentially deleterious effects of sleep deprivation, fatigue and stress on patient safety and individual well-being is not prudent, and it may simply be that we need to modify our training programs in order to pack them with more of the relevant work (which is being done in some cases through the use of physician extenders), or even to extend the duration of the programs, if necessary, so that the trainee can complete their training with a minimal level of competence (which is discussed more completely later in this chapter).

Another major element introduced by the ACGME as a part of the Outcomes project was the introduction of six Core Competencies (medical knowledge, patient care, systems-based practice, practice based learning and improvement, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills). These were introduced on the basis of the reports of the Institute of Medicine [64–67] which emphasized the need to create quality in six domains which included healthcare that is: patient-centered, efficient, effective, safe, timely and equitable [65]. In order to achieve this, the core competencies enveloped a variety of skills that training programs became accountable for teaching and evaluating. The implementation of competency awareness has been perceived, in general to have improved care and to have elevated training programs from “apprenticeships” to more formal and structured educational programs designed to teach life skills.

The introduction of formal quality improvement education into residency and fellowship training (as a result of emphasizing systems-based practice, professionalism, and practice-based learning) has the potential to improve outcomes for patients. Improving quality and outcomes requires excellent technical results from a surgery, accurate diagnosis, meticulous pre and post-operative care to avoid iatrogenic injury (such as central line infections or ventilator-associated pneumonias), and careful outpatient follow-up, particularly for the most vulnerable patient populations such as the interstage single ventricle cohort. In other words, our outcomes are the result of our entire system, not just a single component. Training the next generation of surgeons, anesthesiologists, intensivists and cardiologists to examine care delivery systems and processes and to participate in rapid cycle improvement activities (related to systems-based, not just individual case-based examples) will be essential to improving the quality and outcomes for patients with congenital heart disease.

The changes to duty hours and the incorporation of more broad-based training (through the competencies) were created in an effort to not only improve quality and outcomes for our patients, but to also reduce stress, create more balance and reduce burnout for healthcare providers. Burnout is becoming recognized as an increasingly important factor in medicine that can contribute to errors [68–71]. Most disturbingly, from our own research (unpublished), burnout seems to be prevalent in medical students before they begin medical school, and increases throughout the educational journey. Awareness and recognition of burnout, and attempts to ameliorate it with programs designed to promote wellness, may have an important place in our future training programs.

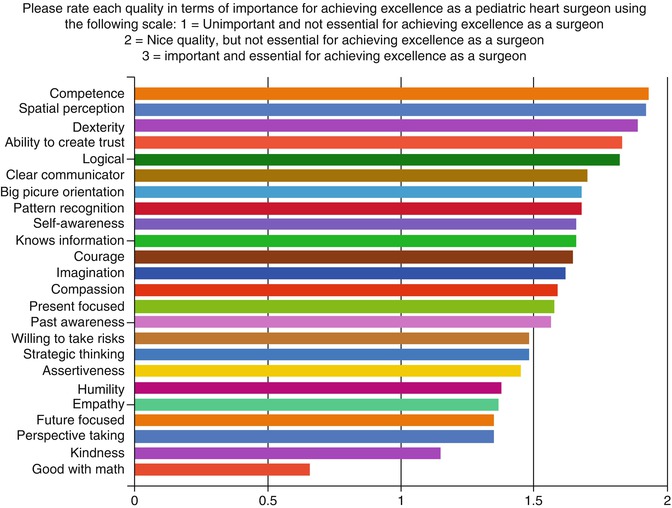

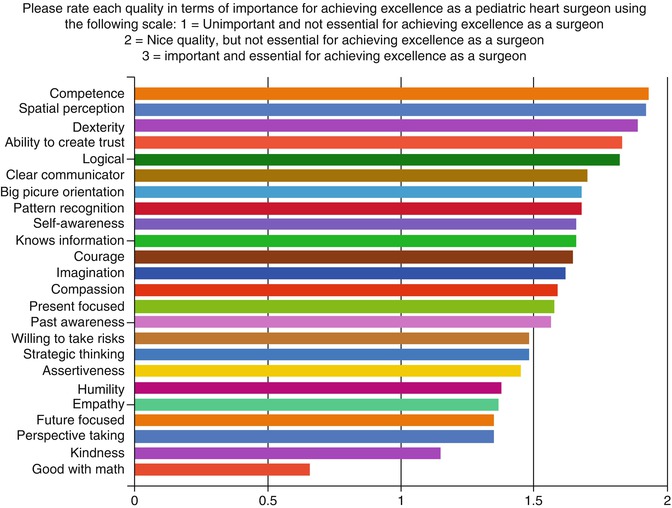

In order to understand better how these changes in our educational structure fit against the backdrop of what our respondents felt was most valuable in their training, we asked pediatric cardiac surgeons about a number of qualities and had them evaluate whether or not they felt that these qualities were important to their achieving success. We believe that these data reflect the prevalent mindsets across our profession. The results are shown in Fig. 2.8 ranked in descending levels of importance.

Fig. 2.8

Factors considered important in achieving excellence as a congenital heart surgeon, ranked by members of the CHSS or EACHS. The longer the bar, the more important the trait

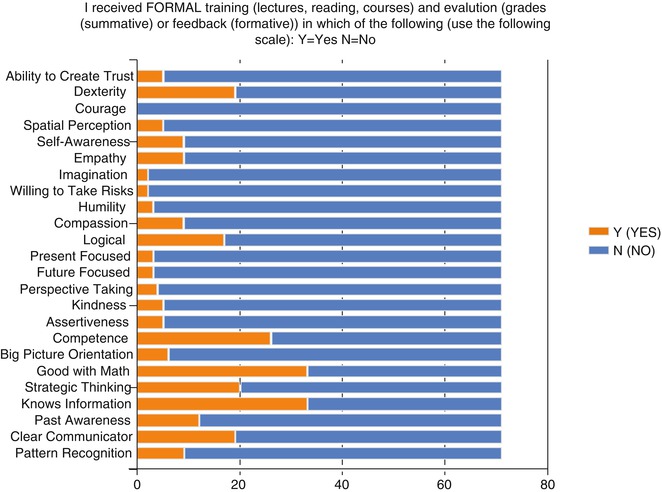

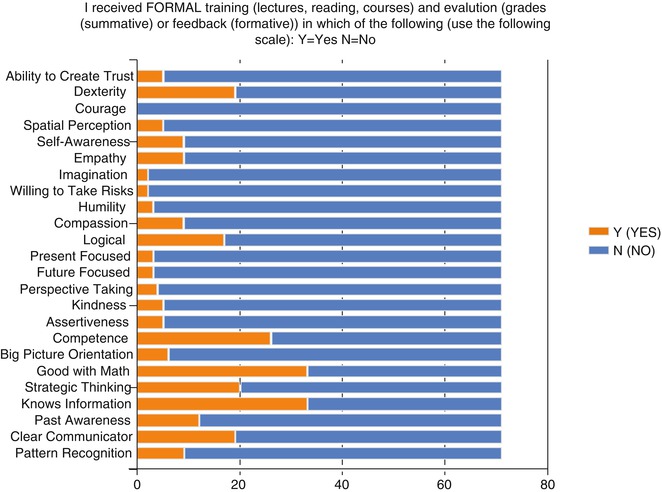

We also inquired about whether or not they received formal education in the qualities they highlighted as important during their training. The results are shown in Fig. 2.9, as stacked bars, indicating the number who felt they had received (orange) versus those who felt they did not receive (blue) formal training in these qualities.

Fig. 2.9

Colored bars indicate whether or not members of the CHSS or EACHS received formal training in various areas. The longer the blue bar, the fewer number of surgeons who felt they were trained in the respective area. The data suggest that most formal training was provided with math and knowledge-based information. There was little training in courage, imagination, risk-taking, humility and kindness

Qualities that were deemed essential by over 75 % of the responders included: competence (meaning ability to perform a procedure without supervision) (93.0 %); spatial perception (91.5 %); dexterity (88.7 %); ability to create trust (83.1 %); and ability to be logical (81.7 %).

Other qualities that were also deemed important by over half the respondents were: clear communication (70.4 %); big picture orientation (67.6 %); pattern recognition (67.6 %); courage (66.2 %); self-awareness (66.2 %); knowledge (66.2 %); imagination (63.4 %); present focus (63.4 %); compassion (59.2 %); willingness to take risks (57.7 %); and past awareness (meaning ability to recall past events in order to incorporate them into making decisions for current events) (57.7 %).

Qualities that were felt to be “nice” but unnecessary to be successful as a pediatric cardiac surgeon (receiving votes from less than half the respondents) included: strategic thinking (47.9 %); assertiveness (46.5 %); future focus (42.3 %); humility (40.8 %); perspective taking (39.4 %); empathy (36.6 %); kindness (21.1 %); and being good with math (5.6 %).

Even though considered important to success, most surgeons did not receive formal training in ability to create trust, spatial perception, or ability to be logical. None received training in courage and very few in self-awareness, empathy, imagination, risk taking, humility, compassion, or other areas which we know to be related to developing emotional intelligence [30, 38, 72].

Most acknowledged some training (as would be expected) in math (although this was felt for the most part to be unimportant and not essential to their success), competence (ability to be self sufficient) and knowledge of medical information, as well as some training in communication and strategic thinking.

The information from this survey indicates a lack of alignment and connectedness between our training programs and the skills/attributes that will be most needed for ultimate success in our field. Self-awareness and ability to create trust are essential components for leadership and felt by many [30, 31, 38, 40, 73–79] to be the most critical foundations for successful leaders to develop. Our current training programs seem to emphasize technical skills (dexterity, medical information and “competence”—meaning the ability to do a task without help). Although not part of a “classic” surgical training curriculum, each of the other qualities listed have been associated with leadership and success, and each can be taught (and learned) [30, 33, 35, 36, 38–40, 75, 76, 79–86].

It is also notable that current training programs have no formal training or education in courage [87], imagination [83, 88–90], risk-taking [76, 78, 91], compassion [79, 84, 92, 93], perspective-taking [1, 41, 86, 94–96], pattern recognition, and many other qualities that can be taught, learned and that are associated with leadership and success [38, 40, 78, 82, 97, 98]. In fact, when choosing what they believed was most important for them to share with their colleagues, the past presidents of our national cardiac surgery organizations (American Association of Thoracic Surgery, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Western Thoracic Surgical Association) have consistently selected topics related to leadership, personal development, courage, compassion and education [1, 87, 99–101]. At this sentinel moment in their careers, these successful surgical leaders have determined that emphasizing “non-technical skills” is the message they wish to share with others.

Current training in pediatric cardiac surgery has changed in the U.S. in the past several years. As general surgery training programs have created fewer opportunities for surgical residents to work on cardiac services, and as the technical components of general surgery have transitioned more to video-assisted, robotic and other non-invasive techniques versus open, hands-on procedures that emphasize cutting and sewing, the residents entering cardiothoracic fellowship programs are less prepared for the technical challenges of cardiac and especially, pediatric cardiac surgery. Yet, these technical skills can certainly be learned and mastered in time—as long as our training programs change and adapt to the current challenges.

The aspiring pediatric cardiac surgeon must now complete an additional year of training following successful completion of cardiothoracic surgery training. This additional year of training must be completed at an ACGME accredited program for pediatric cardiac surgery training and these programs are subject to the same duty-hour restrictions that govern all ACGME accredited programs. In addition, the aspiring trainee is required to perform a specific number and diversity of procedures, show evidence of having received both summative and formative education that is structured and specific to learning congenital heart surgery, and eventually (in order to become board certified) pass a written and then an oral exam.

Many aspiring pediatric cardiologists are also encouraged to complete additional training in the current era. Advanced fellowships with specific national recommendations for the training experiences are available in a variety of subspecialties within pediatric cardiology, such as interventional cardiac catheterization, electrophysiology, echocardiography and MRI, cardiac critical care, and adult congenital heart disease. Unlike surgery, however, at this time, there is no formal exam or board certification (beyond general board certification in cardiology) for any of these subspecialties, although that may be looming on the horizon. Likewise, there is additional training available to those interested in pediatric cardiac anesthesiology. Sub-specialty certification in pediatric anesthesiology is beginning in 2013 and requires 1 year training in an ACGME accredited fellowship and then passing the subspecialty board exam. The training in pediatric anesthesiology does include training in management of children with complex heart disease for cardiac and non-cardiac procedures. However, at the present there is no sub-specialty certification in cardiac anesthesiology although fellowship training is recognized. Further training in pediatric cardiac anesthesiology is available, although no certification or accreditation process is in place.

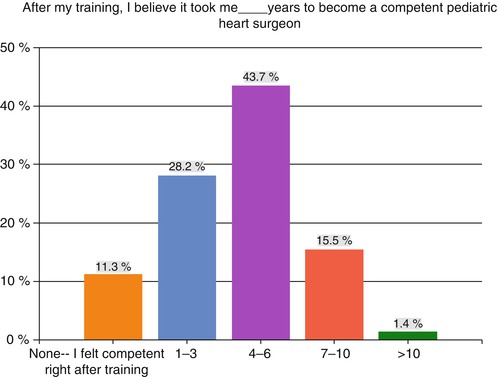

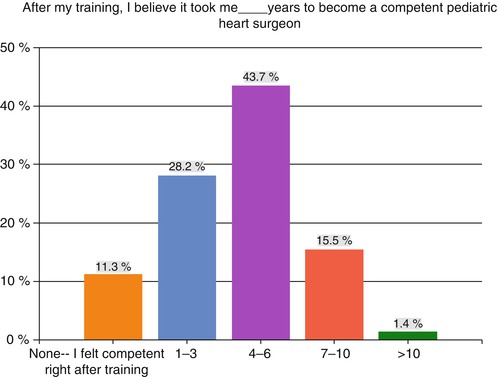

Most pediatric cardiac surgeons consider themselves to either be visual learners (39.4 %–meaning they learn best by seeing or watching someone do something) or experiential learners (43.7 %–meaning they learn best by doing or having an experience of what they are trying to master). An important minority consider themselves to be perceptual learners (16.9 %–meaning they learn best by reading, reflecting and then using those processed thoughts to guide their actions). There were no surgeons surveyed who felt that they were auditory learners (learning best by listening to a talk or hearing someone describe how they do something). (A personal survey of other specialties has revealed a higher percentage of auditory learners, particularly in more medically related fields). While a minority of respondents felt that they were competent pediatric heart surgeons immediately after their training (11.3 %), the largest number felt that the journey to competence after training takes an additional 4–6 years (43.7 %) and some felt that it can take up to 10 years (15.5 %) (Fig. 2.10). For the most part, congenital heart surgeons felt that they continued to learn and develop after their formal fellowship training was completed (and many of these individuals trained in the era before duty hour limitations). The same is true for other congenital cardiac specialists such as anesthesiology, and is likely also the case for interventional cardiology, critical care, or imaging disciplines.

Fig. 2.10

Length of time after formal training that it took for members of the CHSS and EACHS to feel “competent”

While competence (ability to perform routine tasks without supervision) is a likely end product of formal training, extended time to achieve expertise is more consistent with the information on development of expertise requiring focused or “deep” practice for a considerable number (10,000 or more) of hours [37, 94, 102, 103]. It may be that our experts, when responding to this question, had differing perspectives on how they valued their abilities and what, for each of them, constituted competence; with competence for some equating with expertise. Regardless, it is clear that the length of time spent in training is not sufficient to enable attainment of expertise—that takes sustained practice.

Defining stages or levels of competency may be helpful. Competency is the ability to perform a certain task for a work situation without supervision, and to know when to ask for help. It is the intent of most training programs that this is achieved by the end of training. In anesthesia training five stages of adult skill acquisition have been applied: novice, entering training; advanced beginner, at the end of first year of training; competent, at the conclusion of training; proficient, after being in practice 5 years; and expert, after practice for 10–15 years [104]. Regardless, this makes it clear that education and learning continue beyond training and are critically important to attaining the highest degree of proficiency and expertise in all possible scenarios regardless of the discipline.

Lifelong learning itself is a topic that merits discussion, since it is at the foundation of training. The environments that we create for training will ultimately shape those who will become our future educators and mentors.

It is ironic that most health care professionals learned at Teaching Hospitals. Teaching evolves from knowing and a desire to share with others what you know. In 1998, Parker Palmer published “The Courage to Teach” [105] and each year, the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) bestows a Courage to Teach award on some of the nation’s great teachers. All of us recall our most influential and inspiring teachers with fondness, admiration and gratitude. We can also recall some of those teachers who made our ignorance feel painful, shameful and frightening. A “teacher” who contemptuously reprimands a student for “not knowing” or worse, for being “stupid, lazy and insulting their time” does more damage than they likely can imagine. In her work on learning, Carol Dweck [76] describes the kind of attitudes that best correlate with performance excellence, and not surprisingly, they are not related to knowing the answers, but rather to asking the questions, even when the answers seem most elusive. This is why we believe it takes more courage to learn than it does to teach [1]. Learning requires that we accept the vulnerability [80, 106] that accompanies “not knowing” and then embrace a willingness to struggle—and possibly fail—while we try to challenge ourselves (and others who work with us, or who we train) to think differently or to do things we (they) have never done. We all walk because our parents likely created for us an environment that invited learning. You likely don’t remember for yourself, but think of how babies learn to walk. When they fall, we don’t criticize them for being a failure, or tell them that they will never be successful at walking. It is not likely that we compare them to a sibling who was walking sooner and admonish them that they should try to be more like that person. No. We applaud, and smile and encourage them to try again. Until they learn. And we share their joy in accomplishment. What happens that we forget how to do that in our teaching institutions? We have created a culture that rewards “knowing” (expertise) and we worry about what would happen to our patients if we weren’t experts. An inviting reframe of that last statement is “What ‘could’ happen for our patients if we could let go of knowing and instead, keep wondering?”

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree