0.1–0.5 mm vessel

0.6–0.9 mm vessel

1.0–4.0 mm vessels

>4 mm vessels

Hypertonic saline

11.7 %

Saline

11.7–23.4 %

Saline

23.4 %

STD

1–3 %

STD

0.1–0.2 %

STD

0.2–0.3 %

STD

0.3–0.5 %

Polidocanol

2–5 %

Polidocanol

0.2–0.5 %

Polidocanol

0.2–0.75 %

Polidocanol

1.0–2.0 %

Glycerin

50–72 %

The recommended dose of STD by the manufacturer is 2 ml of 1 % or 3 % solution (20 or 60 mg) per injection site with a maximum of 10 ml per treatment session. Polidocanol is recommended at a dose of 0.1–0.3 ml per injection site to a maximum of 10 ml per treatment session.

Indications and Contraindications

Optimal indications for sclerotherapy include telangiectasias, reticular veins, isolated varicosities, below-knee varicosities, and recurrent varicosities. Less than optimal indications include symptomatic reflux, aged, or infirm patients who are not surgical candidates. Debatable indications are SFJ reflux, SPJ reflux, large varicosities, and large perforators which are refluxing [21, 22].

Contraindications for sclerotherapy include allergy to sclerosant, bedridden patients, post-thrombotic syndrome, acute thrombophlebitis, uncontrolled malignancy, and local or severe systemic infections [21, 22].

Sclerotherapy has been extensively used to treat axial refluxes and large incompetent perforators. More evidence is needed before this can be recommended for widespread practice. With the available evidence, it may be ideal to treat axial refluxes and large veins by surgery or by endovenous thermal ablation. This can be followed by sclerotherapy for smaller veins and telangiectasias [23].

Types of Sclerotherapy

Microsclerotherapy and macrosclerotherapy were the techniques in common use when liquid sclerosant alone was available. Foam sclerotherapy was introduced with the invention of foam sclerosant. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (USGFS) and catheter-directed foam sclerotherapy are further modifications. They are more effective and produce fewer complications [24].

Microsclerotherapy

This term refers to the treatment of telangiectatic blemishes and reticular veins using liquid sclerosant [25]. Weak sclerosing solutions are generally used for the procedure. Pretreatment duplex scan can reveal an incompetent saphenous and perforating system refluxing into these vessels [26]. The source of venous hypertension which has led to the development of these lesions must be controlled before therapy. The feeding reticular veins connecting to the telangiectasias should be injected first. If such a feeding vein cannot be identified, telangiectasias can be injected directly, beginning at the point at which the branches converge. Although liquid sclerotherapy is ideal for C1 class [27–29], foam sclerotherapy is an additional option [30–32].

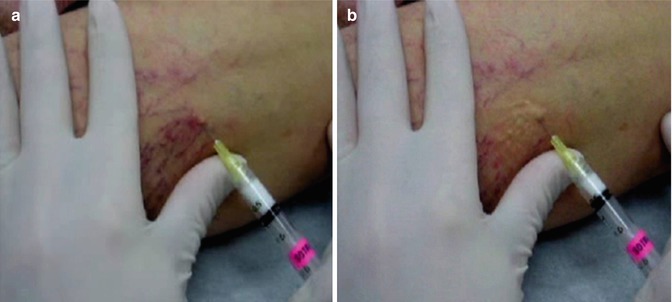

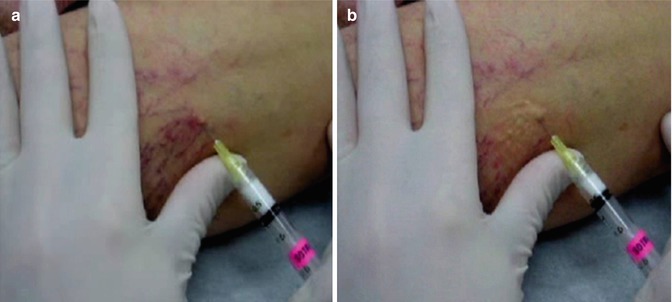

The technique of injection varies among different practitioners. The patient is in horizontal position and the skin is cleaned with alcohol to remove the excess keratin and allow better visualization of the target vessel. Thirty G needles, bent to 10–20°, fitted with 1 ml syringes are employed for injection. Skin adjacent to the vein is stretched and the needle is introduced into the vein tangentially. Gentle pressure on the plunger ejects sclerosant into the vein. Magnification and good light can improve the performance. Injections should be performed very slowly taking 10–15 s. The amount of sclerosant per injection site should be limited to 0.1–0.2 ml (Fig. 9.1).

Fig. 9.1

Microsclerotherapy. (a) Cannulation. (b) Postinjection with blanching

Persistent blanching of skin to a waxy white color indicates extravasation. If such an event occurs, the area should be flushed thoroughly with normal saline to dilute the extravasated sclerosant and relieve vasospasm. Veins larger than 0.5 mm and protruding above the skin surface should have sustained compression for 72 h at least following injection. Small veins that do not protrude above the skin surface need not be compressed. Class II compression therapy is provided after completion of injection. Protuberant telangiectasias and large reticular veins need compression for at least 72 h. Patients who need multiple sessions are called at 2–4 weeks interval. In case of reticular varicosities, volume of injection can be 0.5 ml per site. Multiple punctures give best results [21, 33]. We have used 0.25 % sodium tetradecyl sulfate and 0.5 % polidocanol for microsclerotherapy.

Macrosclerotherapy

Macrosclerotherapy is the method of treatment of larger veins (tributaries and truncal veins) using liquid sclerosing agents. The sclerosants used for this purpose are 1–1.5 % sodium tetradecyl sulfate or 1–2 % polidocanol. Multiple site injections are followed by compression for at least 2 weeks. This technique has largely been replaced by foam sclerotherapy.

Foam Sclerotherapy

Foam sclerotherapy (FS) is a method of endovenous chemical ablation using foamed sclerosants. There are several advantages for this technique.

FS fills up the large veins into which it is injected by expanding the volume of the sclerosant injected. The sclerosing agent which is at the surface of the bubbles establishes good contact with the endothelium. Once the gas gets absorbed, the vein walls collapse. The chemical action on the endothelium would be initiated by this time.

Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (USFS) has an additional advantage that the sclerosant can be tracked in the vein lumen, since air is a good contrast medium. Ultrasound permits selective guided venous puncture avoiding injury to adjacent arteries. It also permits a postinjection evaluation of the extent of distribution of the sclerosants and its reaction on the vein wall [34–37].

USFS is an office-based procedure not requiring hospitalization.

It is cost-effective compared to other modalities like HL/S or endovenous thermal ablation.

In the event of recurrence, the procedure can be repeated easily.

Foam Generation

Detergent-type sclerosants such as polidocanol or sodium tetradecyl sulfate can be transformed into fine-bubbled foam by special techniques. It is produced by turbulent mixture of liquid and gas in two syringes connected via a three-way stopcock, Tessari method. In the original Tessari method, the ratio of sclerosant to gas was 1:4 [16]. The Tessari double-syringe-system (DSS) technique involves the turbulent mixing of sclerosant with gas in a ratio of 1:4 in two syringes linked via a two-way connector. The use of atmospheric air in foam production does not give rise to any adverse effects [38].

In our experience, we could obtain stable and fine-bubbled foam by a modified Tessari technique. The required materials are two 10-ml syringes with a Luer-Lock connection (omnifix syringe and inject syringe), one three-way adaptor, and a 0.2-mm filter for sterilization of air. 8 ml of air is drawn into the inject syringe via the sterile filter. Air filter is discarded and 2 ml of 3 % polidocanol is also drawn into the syringe. The two syringes are connected through the three-way adaptor. The air sclerosant mixture is passed between the two syringes to generate foam. The initial five passages are done by offering mild resistance to the piston of the recipient syringe. Further 15 passages are performed without any resistance (Fig. 9.2). This will generate a foamed sclerosant of 10 ml. The DSS technique offers a fixed sclerosant-air ratio of 1:4, a half-life of approximately 150 s, and an initial bubble size of 70 μm [39].

Fig. 9.2

Generation of foam sclerosant

Technique of Injection

In our practice, all patients with significant axial reflux had a preliminary high ligation under local anesthesia. Multiple site cannulation of the dilated and tortuous veins with 22G cannula or butterfly needle (4–6 sites) is preformed under US guidance (Fig. 9.3).

Fig. 9.3

Cannulation of the vein

Each site is injected with 2–3 ml of foam with limb elevated to 45° angle and monitored by US imaging (Fig. 9.4).

Fig. 9.4

Injecting foam sclerosant

In cases with nonsignificant reflux or no reflux at SF junction, high ligation is avoided, and USFS alone is done. In such cases, one of the requirements is to prevent the spillage of FS into the femoral vein. One technique is to track the foam with ultrasound, and once it reaches the SF junction, compression is applied at the site with the duplex probe followed by compression bandage. On completion, the distribution of the sclerosant and the reaction of the vein including spasm are checked. Injection is followed by immediate compression using gauze pad and elastic bandage and maintained for 2 weeks. Histological studies suggest that at least 12 days of fibroblastic healing is required for obliteration of moderate-sized veins [17]. Fegan had suggested 6 weeks of compression following liquid sclerotherapy. The length of compression treatment period varies between different authorities. In our practice, 2 weeks of compression treatment is given following foam sclerotherapy. After two weeks, the patient is advised to wear class II compression stockings for the next 4 weeks.

Nearly all workers in this field advise that the patient should walk for at least 30 min after the procedure. This will permit any allergic reaction to be manifested and treated. The comfort of the elastic compression can also be evaluated. Ambulation promotes deep venous circulation to flush out any sclerosant that has spilled over [21].

All our patients were assessed with duplex ultrasound scan at 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year.

Outcome

During a 2-year period, we treated 40 patients with C5–C6 clinical class with combined high ligation and distal USFS. Ninety percent of the limbs showed obliteration of the injected veins at the end of the 6 months. There was an upgradation of CEAP class in all our patients. The ulcers healed in all the C6 class patients. Two patients had superficial thrombophlebitis and two patients had calf vein thrombosis. All patients settled with treatment. No major/minor neurological events were noted in our patients (Fig. 9.5).

Fig. 9.5

Foam sclerotherapy outcome (a) a leg with varicose veins before foam sclerotherapy, (b) the same leg after foam sclerotherapy

Saphenectomy combined with ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy is reported to give results equivalent to classical surgery in terms of obliteration of veins, ulcer healing, and improvement of CEAP class. The time taken for USFS was significantly lower (45 min vs 85 min) [40, 41]. The role of surgery and thermal ablation in the treatment of incompetent saphenous system is well established. Many groups have used sclerotherapy in isolation for this purpose and have reported comparable results [28, 42–46]. One of the requirements is to prevent the spillage of FS into the femoral vein. One technique is to track the foam with ultrasound, and once it reaches the SF junction, compression is applied at the site with the duplex probe followed by compression bandage (Fig. 9.6).

Fig. 9.6

Tracking of foam sclerosant with ultrasound

Another method is using Sigg’s technique with an inflatable balloon called Safeguard® for echo-guided compression of saphenofemoral junction [47]. For optimum control, it will be more logical to inject the FS close to the source of reflux, a perforating vein/saphenous junctions. Carbon dioxide or CO2/O2 mixture has been used to make foam instead of air. No extra advantages are reported with these methods. Total volume of sclerosant required for treatment was more with CO2 foam group [48].

A recent modification of USFS is a catheter-directed foam sclerotherapy. An angiography catheter is introduced into the GSV at or below knee under US guidance and advanced up to the saphenofemoral junction. Saphenofemoral junction is occluded and then the catheter is slowly withdrawn while injecting foam through the catheter. The technique allows more precise delivery of the required quantity of foam into each segment of the vein to be obliterated [49]. It resembles endovenous ablation using RFA or laser. Foam sclerotherapy using triple-lumen double-balloon catheters are reported, but no extra benefits were observed. In 70 % of cases, occlusion was complete at 1 year, partial in 14 %, and in 16 %, there was recanalization [50].

Bilateral varicose veins can be treated with foam sclerotherapy at a single sitting without affecting the vein occlusion rate or increasing the complications. Volume of foam sclerosant required would be obviously higher in bilateral groups compared to unilateral (17.5 ml vs 10 ml) [51].

Results of foam sclerotherapy have been compared with the results of standard surgery as well as with laser and radiofrequency ablation techniques. Comparative results with liquid sclerotherapy are also available. Foam sclerotherapy is found to be more effective than liquid sclerotherapy. Both sodium tetradecyl sulfate and polidocanol are equally effective when used as foam [52]. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy was found to be associated with less pain and analgesia requirement, time off work, and quicker return to driving compared with conventional surgery [43]. At the end of 2 years, recurrent reflux irrespective of venous symptoms was more in USFS group compared to classical surgery (35 % vs 21 %) [43]. But symptomatic recurrence was found to be comparable. The reduction in cost of treatment was significant with USFS [53].

The technical failure rate at the end of one year was highest after USFS in comparison to surgery and endovenous thermal ablation (USFS 16.3 %, conventional surgery 4.8 %, laser 5.6 %, and RFA 4.8 %). The pain scores were significantly low with RFA and USFS and highest with laser and conventional surgery [43]. In recurrent varicose veins, USFS was found to be superior to surgery. A single session of USFS can eradicate reflux in above-knee and below-knee great saphenous vein in over 93 % of patients with symptomatic recurrent great saphenous vein varicosities [54].

Foam sclerotherapy is generally safe in the treatment of short saphenous varicosities also. Medial gastrocnemius vein thrombosis is reported in 0.6 % patients following USFS of SSV. Two anatomical features that can aggravate risk of DVT are relevant in this context. Direct entry of the SSV into popliteal vein and the presence of medial gastrocnemius vein perforators [55]. An early duplex scan may be ideal in such patients.

Complications of Sclerotherapy

Sclerotherapy is an efficient method of treatment with a low incidence of complications, if performed in a systematic manner [56]. Some of the commonly encountered complications are discussed below.

Anaphylaxis

Thrombophlebitis

Reported incidence of thrombophlebitis varies from 0 to 45.8 % (mean 4.7 %) [58–60]. However, the definition of phlebitis after sclerotherapy in the literature is controversial. An inflammatory reaction at the injected part of the vein should not be taken as phlebitis. Superficial thrombophlebitis can develop after sclerotherapy, but its real frequency seems to be low [22]. Incidence of thrombophlebitis can be minimized with compression therapy after sclerosant injection.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Severe thromboembolic events (i.e., proximal DVT/pulmonary embolism) occur only rarely after sclerotherapy. The overall incidence of thromboembolic events is less than 1 % [60–62]. Most of the DVTs were distal and asymptomatic [63, 64]. Large volume FS increases the risk of DVT [65–67]. Patients with previous history of DVT or thrombophilia warrant additional prophylactic measures [65, 68]. Deep vein thrombosis can be obviated by post sclerotherapy exercises that flush the deep veins.

Cutaneous Necrosis

Skin ulceration and cutaneous necrosis can result from extravasation of the sclerosant or from injection into a terminal arteriole [69]. This can happen during injection of reticular veins or telangiectasias [70, 71]. This has been described as embolia cutis medicamentosa or Nicolau phenomenon [72, 73]. Complication of extravasation can be minimized by using dilute solutions, especially in telangiectasias and also by slow injection of small quantities to each site.

Hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation can occur following treatment of reticular veins and telangiectasias. Reported frequency is 0.3–30% in the short term [69, 74]. It is most common following sodium tetradecyl sulfate and hypertonic saline and least with polidocanol and chromated glycerin. Pigmentation is due to hemosiderin derived from the extravasated RBCs. This may be minimized by the use of weak solutions and minimum pressure during injection. Any coagulum formed should be removed by minithrombectomy [75]. Post sclerotherapy hyperpigmentation largely disappears over a prolonged period [76].

Telangiectatic Matting

Telangiectatic matting or neoangiogenesis is the appearance of red telangiectasias at the site of sclerotherapy. It can also occur after surgical or thermal ablation of varicose veins [69]. All the measures to prevent pigmentation can be practiced here also. Residual reflux if any should be eliminated [59]. Pulsed-dye laser therapy for the treatment of neoangiogenesis has been found to be effective [21].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree