Sarcomas of the Heart and Great Vessels

Joseph J. Maleszewski, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Sarcomas of the Heart

General Features

Approximately 10% of primary cardiac tumors are malignant, and the vast majority of these are sarcomas. The current accepted classification is based on histologic appearance. The most frequent cardiac sarcoma that exhibits lineage-specific differentiation is angiosarcoma, but most cardiac sarcomas exhibit little (if any) differentiation.

Owing to their rarity, it is difficult to conduct large series to evaluate histologic grading and staging of cardiac sarcomas. Nevertheless, the current WHO classification has largely adapted the schemes used in noncardiac mesenchymal malignances to those seen in the heart. Such includes evaluation of cellular differentiation, necrosis, and mitotic activity. Grading systems such as the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, which are available in the College of American Pathologist Cancer Protocols as well as the American Joint Committee on Cancer, have also been employed.1

Regardless of the grading/staging system employed, most of these lesions carry a grave prognosis, with death often occurring within months of the diagnosis. Treatment is typically aimed at palliation and typically consists of surgical resection and/or adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy.

Angiosarcoma

Definition

Cardiac angiosarcoma is a primary cardiac sarcoma exhibiting primarily endothelial differentiation.

Epidemiology

Angiosarcoma is the most common primary cardiac malignancy with differentiation, accounting for ˜40% of cardiac sarcomas in the larger series reported.2 Because they are often infiltrative and not amenable to surgical excision, they tend to represent a relatively small proportion of cardiac tumors in surgical series.

Clinical and Radiologic Features

Cardiac angiosarcomas occur over a wide age range (mean, 40 years), with no strong sex predilection. Nearly all lesions are sporadic in nature, but familial cases have been rarely reported.3

Cardiac angiosarcoma results in a variety of cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, and pericarditis. When the pericardium is involved, hemopericardium and tamponade may occur and are more commonly seen in the setting of angiosarcoma (compared to other cardiac malignancies) owing to the vascular nature of

the lesion. There may be a misdiagnosis of chronic pericarditis leading to delay in diagnosis. The first clinical manifestations may relate to metastatic disease, which is common.4

the lesion. There may be a misdiagnosis of chronic pericarditis leading to delay in diagnosis. The first clinical manifestations may relate to metastatic disease, which is common.4

Echocardiographically, cardiac angiosarcomas are usually echogenic and lobulated. Pericardial effusion is also frequently seen. Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) usually reveal a heterogeneous, nodular mass. The vascular nature of the tumor is well demonstrated with contrast studies.4 Multimodality imaging is useful in characterization of the tumor and in guiding biopsy of the lesion of interest.

Cardiac angiosarcoma is diagnosed by open biopsy, mediastinoscopy, echocardiogram-guided fine needle aspiration, and pericardial biopsy. Cytologic examination of pericardial effusion has not proven very sensitive. Transvenous endomyocardial biopsy guided by transesophageal echocardiography is relatively a noninvasive mode of diagnosis.5

Location and Gross Pathology

Most cardiac angiosarcomas arise in the right atrium, usually in the region of the atrioventricular sulcus. The tumor frequently replaces the right atrial free wall and protrudes into the chamber and/or pericardial space. The tumor often involves the pericardium as well. Left atrial angiosarcomas have also been described, but occur in <10% of cases (Table 184.1).

Grossly, cardiac angiosarcomas are red-brown (hemorrhagic), irregular masses that generally range from 2.0 to 10 cm in size. Occasionally, the tumors can appear more fleshy and yellow-white. The tumors usually exhibit extensive infiltration of the adjacent myocardial tissue and may significantly protrude into the atrial cavity or into the pericardial space.

Histopathology

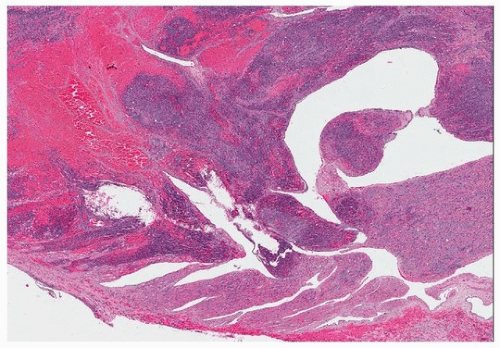

Histologically, cardiac angiosarcomas have a rather variable appearance. Nearly two-thirds of tumors are relatively well differentiated, with the bulk of the tumor composed of malignant endothelial cells forming papillary structures and/or anastomosing, irregular, vascular spaces. The lining cells are atypical and usually pleomorphic. Mitotic activity is usually abundant (Fig. 184.1).

The remaining third consist of poorly differentiated, spindle cell, lesions. These lesions often contain abundant red blood cells, some of which appear to be contained within intracytoplasmic vacuoles (intracellular lumina).

As noted above, there is no established grading system for cardiac angiosarcomas. They are generally considered high grade regardless of histologic features. Nevertheless, the presence of necrosis and a high proliferative index may portend an incrementally more aggressive process.

TABLE 184.1 Frequency of Histologic Subtypes of Cardiac Sarcomas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for endothelial markers is useful. The most sensitive markers include CD31, ERG, and Fli-1. CD34 is not as specific for endothelial cells, but is usually reactive with the neoplastic cells.

Prognosis

The survival of patients with angiosarcoma of the heart is relatively poor in comparison with other cardiac sarcomas. A median survival of 13 months has been reported, with better survival among patients with localized disease.6 A recent report showed a mean survival of 29 months.7

Cardiac angiosarcomas have an especially poor prognosis because they typically present with metastatic disease, often in multiple sites, including the lung and bone.

Differential Diagnosis

Well-differentiated cardiac angiosarcomas are uncommon, but may be confused with hemangiomas. The latter can be intramyocardial and appear infiltrative, but lack the pleomorphism and mitotic activity of angiosarcoma.

Papillary endothelial hyperplasia may occur within atrial thrombi and can mimic the anastomosing growth pattern of cardiac angiosarcoma; however, infiltrative growth and atypia are absent.

Other cardiac sarcomas may also be confused with angiosarcoma, particularly in cases of spindle cell angiosarcomas. In these instances, immunohistochemistry is very useful to demonstrate endothelial antigenicity.

Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma

Definition

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas are high-grade sarcomas showing no specific pattern of differentiation based on ancillary studies. In the past, these lesions have been referred to as undifferentiated sarcomas, intimal sarcomas, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. The precise cell of origin is unknown.

Epidemiology

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas are as or slightly more common than cardiac angiosarcoma. They typically occur at an average age between 40 and 50 years with no obvious sex predilection.

Clinical and Radiologic Features

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas of the heart may present with symptoms related to direct effects of the primary tumor such obstruction (e.g., mitral stenosis, pulmonary vein stenosis, etc.) or symptoms related to metastases to other sites. The latter are particularly common with this aggressive entity.

As with other cardiac tumors, echocardiography can establish the presence of a mass lesion in most instances. CT and cMRI can provide additional information on the tissue characterization (presence of fat and/or calcification). They also provide more spatial resolution that can help to assess for invasion and improve surgical planning as well as posttreatment follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree