Aneurysmal dilation of a saphenous vein aortocoronary graft remains a rare complication. We report a patient with saphenous vein graft aneurysm who presented with abdominal pain due to compression of the adjacent liver 43 years after the coronary bypass operation.

Saphenous vein graft (SVG) aneurysm is usually a diagnostic challenge because it can present in a myriad of symptoms, with chest pain being the most frequent complaint. We report here the first case of SVG aneurysm presenting as abdominal pain 43 years after the coronary bypass operation.

Case Description

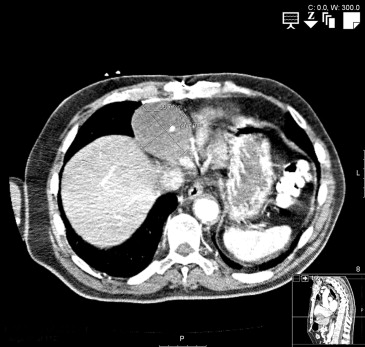

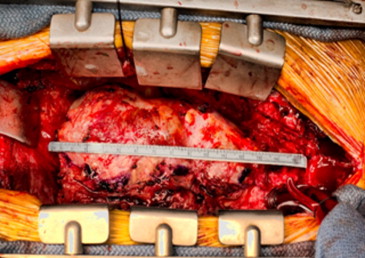

An 83-year-old man with hypertension and hypercholesterolemia underwent coronary artery bypass grafting on 3 separate occasions: first in 1970 (age 39 years) with right internal mammary artery to left anterior descending artery and then in 1982 (age 51 years) with left internal mammary artery to left circumflex, and then SVG to the right coronary artery (RCA) in 1999 (age 68 years). He also underwent stenting to the vein graft to the RCA in 2007 (age 76 years) with a drug-eluting stent. Catheterization in 2012 showed patent grafts. He presented with sudden-onset right upper abdominal pain that started at rest. Computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen showed a cystic lesion anteriorly in the cardiophrenic angle of 6.5 cm in diameter and a calcified fusiform abdominal aortic aneurysm of 3.6 cm ( Figures 1 and 2 ). A computed tomography angiogram demonstrated a patent vein graft with a 6.7 × 5.8 cm aneurysm with mural thrombus at the level of the inferior atrioventricular groove. Angiography confirmed the aneurysm in the vein graft to the RCA as well as a patent left internal mammary artery and right internal mammary artery. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 50% and possible extracardiac structure compressing the right atrium and the right ventricle. At operation, the SVG aneurysm measured 6 cm in diameter ( Figure 3 ) and was filled with thrombus and involved the SVG to the RCA. A new SVG was placed to the distal RCA. The previous vein graft anastomotic site in the ascending aorta was oversewn with pledgeted 3-0 Prolene sutures. Postoperatively, cardiogenic shock and new-onset atrial fibrillation occurred, but he steadily recovered and was discharged to a nursing home 16 days after the operation. Fifteen days after discharge, he regained his full strength and went home. Surgical pathology was read as pseudoaneurysm without calcifications.

Discussion

Aneurysmal dilatation of SVG used in coronary artery bypass graft remains a rarely reported complication. Although a minor degree of SVG dilatation has been reported to be as high as 14% at 6 to 12 years, a large or symptomatic aneurysm of the SVG is rarely observed or reported. The incidence of this complication at 10 to 20 years after coronary artery bypass graft is unclear as it is possible that only a minority of cases come to clinical attention; yet it is estimated to be <1%, as there have been fewer than 100 additional cases reported since 1975. Notably, there have been no reported cases in the literature of any internal mammary graft aneurysms.

A review of 50 cases of SVG aneurysm by Kalimi et al noted that only 2 of 3 were true aneurysms, whereas almost 1 of 3 were pseudoaneurysms and a few were indeterminate. Pseudoaneurysms have been discovered as early as a few days postoperatively and as late as 23 years after coronary artery bypass grafting. Their usual appearance is at the anastomotic suture lines likely due to suture rupture. Other causes implicated in pseudoaneurysm development in SVG are graft infection and postoperative mediastinitis.

True SVG aneurysms are usually discovered >5 years after coronary artery bypass grafting. The few cases of early presentation of SVG aneurysm are attributed to an inherent weakness of the venous wall due to lack of circular muscle at the site of venous valves. The cause of late-developing aneurysms is incompletely understood but believed to involve developing atherosclerosis and thrombus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, as well as defects to the vein graft itself, and trauma.

SVG aneurysms are often asymptomatic and many times are suspected because of an unusual chest x-ray. Often, SVG aneurysms require multiple imaging modalities to determine the best management strategy. Although coronary angiography is excellent in determining the coronary anatomy and the need for revascularization, it might underestimate the true size of the aneurysm because of the presence of mural thrombi. Intravascular ultrasonography has been used in a few cases and provided a unique approach to imaging these aneurysms. Similarly, transesophageal and transthoracic echocardiography can be used to assess serial measurements of pseudoaneurysm size and provide insight regarding of the intraluminal pathology. Cross-sectional imaging modalities such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging remain the most reliable imaging modalities and have been used in most cases to finalize the diagnosis and to assess for additional mechanical complications. Contrast can be added to the computed tomography or the magnetic resonance imaging to provide even more definitive information on the shape, size, and any internal communications or fistulae in the SVG aneurysm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree