S

Sarcoidosis

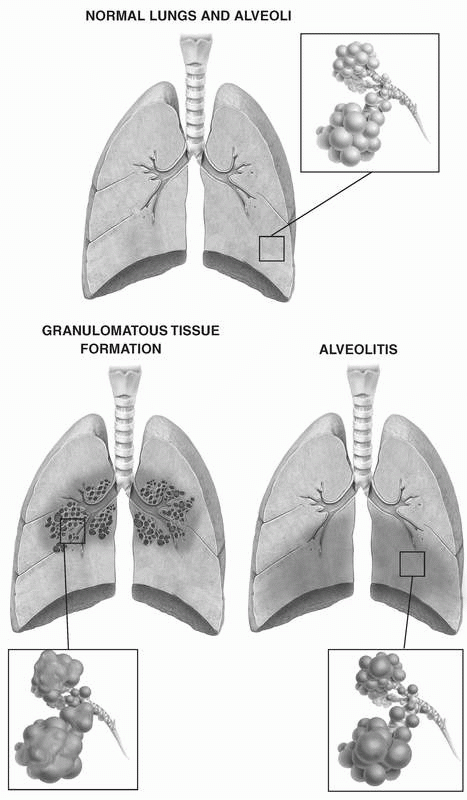

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, granulomatous disorder that characteristically produces lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltration, and skeletal, liver, eye, or skin lesions. Acute sarcoidosis usually resolves within 2 years. Chronic, progressive sarcoidosis, which is uncommon (occurring in 10% of cases), is associated with pulmonary fibrosis and progressive pulmonary disability.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, but several factors may play a role, including a hypersensitivity response (possibly from T-cell imbalance) to such agents as atypical mycobacteria, fungi, and pine pollen; a genetic predisposition (suggested by a slightly higher incidence of sarcoidosis within the same family); and an extreme immune response to infection.

Organ dysfunction results from an accumulation of T lymphocytes, mononuclear phagocytes, and nonsecreting epithelial granulomas, which distort normal tissue architecture. Evidence suggests that the disease is a result of exaggerated cellular immune response to a limited class of antigens.

The disease’s true prevalence isn’t known because of underreporting in younger populations. It occurs at an annual incidence in adults of 10.9 per cases 100,000 people in whites and 35.5 cases per 100,000 people in blacks. In both children and adult, sarcoidosis may be asymptomatic and remain undiagnosed.

More than 70% of childhood cases in the United States occur in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Arkansas, suggesting the southeastern and south central states are endemic for childhood sarcoidosis. Most reported childhood cases occur in patients ages 13 to 15 years; in adults, the majority of cases are reported in patients ages 20 to 30 years. (See Lung changes in sarcoidosis, page 168.)

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Initial indications of sarcoidosis include arthralgia (in the wrists, ankles, and elbows), fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Other clinical features vary according to the extent and location of the fibrosis:

• Respiratory sarcoidosis is marked by breathlessness, cough (usually nonproductive), and substernal pain.

• Cutaneous involvement can cause erythema nodosum, subcutaneous skin nodules with maculopapular eruptions, and extensive nasal mucosal lesions.

• Ophthalmic involvement can cause anterior uveitis and glaucoma.

• Lymphatic sarcoidosis can result in bilateral hilar and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

• Musculoskeletal signs and symptoms include muscle weakness, polyarthralgia, pain, and punchedout lesions on phalanges.

• Hepatic involvement causes granulomatous hepatitis.

• Genitourinary involvement can cause hypercalciuria.

• Cardiovascular involvement can result in arrhythmias.

• Central nervous system signs and symptoms include cranial or peripheral nerve palsies, basilar meningitis, seizures, and diabetes insipidus.

COMPLICATIONS

• Pulmonary fibrosis

• Pulmonary hypertension

• Cor pulmonale

DIAGNOSIS

• Typical clinical features with appropriate laboratory data and X-ray findings suggest sarcoidosis.

• A positive skin lesion biopsy supports the initial diagnosis.

• Chest X-rays reveal bilateral hilar and right paratracheal adenopathy with or without diffuse interstitial infiltrates; occasionally, large nodular lesions present in lung parenchyma.

• Lymph node or lung biopsy reveals noncaseating granulomas with negative cultures for mycobacteria and fungi.

• Pulmonary function tests show decreased total lung capacity and compliance as well as decreased diffusing capacity.

• Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis reveals decreased arterial oxygen tension.

• A negative tuberculin skin test, fungal serologies, and sputum cultures for mycobacteria and fungi as well as negative biopsy cultures help rule out infection.

TREATMENT

Sarcoidosis that produces no symptoms requires no treatment. Because sarcoidosis can cause varied signs and symptoms, pulmonologists, rheumatologists, and ophthalmologists may need to be consulted to provide specific care for those areas affected. Those severely affected with sarcoidosis require treatment with corticosteroids. Such therapy is usually continued for 1 to 2 years, but some patients may need lifelong therapy. If organ failure occurs (although this is rare), transplantation may be required. Patients with hypercalcemia should maintain a low-calcium diet and avoid direct exposure to sunlight.

Drugs

• Corticosteroids such as prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone) to deter granuloma formation and reduce inflammation

• Azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan) to act as a steroid-sparing agent, which affects the autoimmune process, to prevent inflammation caused by the infection

• Chlorambucil (Leukeran) used to act as a steroid-sparing agent and, at high doses, as an alkalizing agent

• Cyclosporine (Neoral, Gengraf), a fungus-derived cyclic peptide, to suppress activated T-cells in the lungs

• Immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate (Folex PFS, Rheumatrex) for persistent active or progressive disease unresponsive to corticosteroids to deter granuloma formation and reduce inflammation

• Pentoxifylline (Trental) to inhibit formation and maintenance of granulomas

• Infliximab (Remicade) monoclonal antibody to neutralize tumor necrosis factor antagonists, which are thought to accelerate the inflammatory process in sarcoidosis

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Watch for and report any complications. Be aware of abnormal laboratory results (anemia, for example) that could alter patient care.

• For the patient with arthralgia, administer analgesics as ordered. Record signs of progressive muscle weakness.

• Provide a nutritious, high-calorie diet and plenty of fluids. If the patient has hypercalcemia, suggest a low-calcium diet. Weigh the patient regularly to detect weight loss.

• Monitor respiratory function. Check chest X-rays for the extent of lung involvement; note and record any bloody sputum or increase in sputum. If the patient has pulmonary hypertension or end-stage cor pulmonale, check ABG levels, observe for arrhythmias, and administer oxygen, as needed. Also monitor spirometry and the diffusing capacity of carbon dioxide.

• Because steroids may induce or worsen diabetes mellitus, perform fingerstick glucose tests at least every 12 hours at the beginning of steroid therapy. Also, watch for other steroid adverse effects, such as fluid retention, electrolyte imbalance (especially hypokalemia), moon face, hypertension, and personality change. During or after steroid withdrawal (particularly in association with infection or other types of stress), watch for and report vomiting, orthostatic hypotension, hypoglycemia, restlessness, anorexia, malaise, and fatigue. Remember that the patient on long-term or high-dose steroid therapy is vulnerable to infection.

• When preparing the patient for discharge, stress the need for compliance with prescribed steroid therapy and regular, careful follow-up examinations and treatment. Refer the patient with failing vision to community support and resource groups as well as the American Foundation for the Blind if necessary.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory infection that can progress to pneumonia and, eventually, death. The disease

was first recognized in 2003 with outbreaks in China, Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam, with other countries—including the United States—reporting smaller numbers of cases.

was first recognized in 2003 with outbreaks in China, Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam, with other countries—including the United States—reporting smaller numbers of cases.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

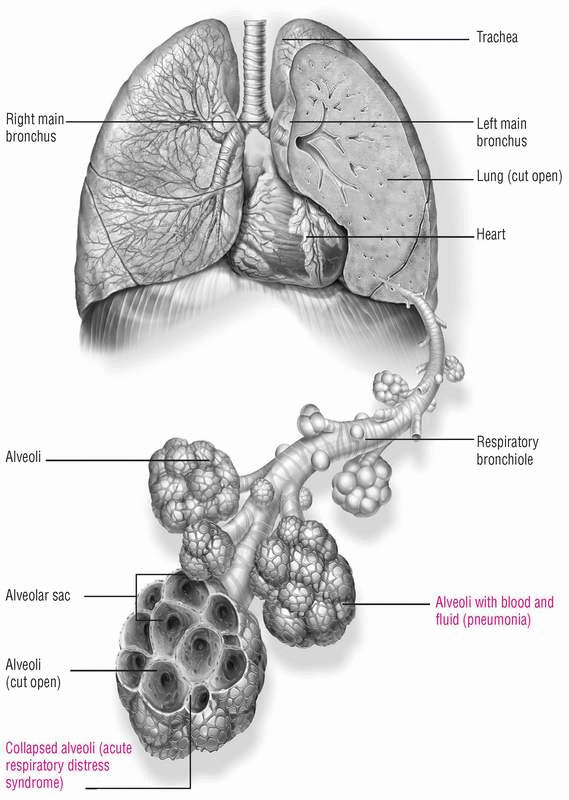

SARS is caused by the SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Coronaviruses are a common cause of mild respiratory illnesses in humans, but researchers believe that a virus may have mutated, allowing it to cause this potentially life-threatening disease.

Close contact with a person who’s infected with SARS, including contact with infectious aerosolized droplets or body secretions, is the method of transmission. The disease can be acquired after the skin, respiratory system, or mucous membranes come into contact with infectious droplets propelled into the air by a coughing or sneezing patient with SARS. SARS may also be spread when a person touches infectious secretions or a contaminated surface or object and then directly contacts his or her own eyes, nose, or mouth.

Most people who contracted the disease during the 2003 outbreak contracted it during travel to endemic areas. However, the virus has been found to live on hands, tissues, and other surfaces for up to 6 hours in its droplet form. It has also been found to live in the stool of people with SARS for up to 4 days. The virus may be able to live for months or years in below-freezing temperatures. (See Lungs and alveoli in SARS, page 172.)

The overall mortality rate of SARS is 10%. However individuals older than 65 years have a mortality rate above 50%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and World Health Organization.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The incubation period for SARS is typically 3 to 5 days but may last as long as 14 days. Initial signs and symptoms include:

• fever

• shortness of breath and other minor respiratory symptoms

• general discomfort

• headache

• rigors

• chills

• myalgia

• sore throat

• dry cough

• diarrhea or rash (in some individuals).

COMPLICATIONS

• Respiratory failure

• Liver failure

• Heart failure

• Myelodysplastic syndromes

• Death

DIAGNOSIS

• Diagnosis of severe respiratory illness is made when the patient has a fever greater than 100.4° F (38° C) or upon clinical findings of lower respiratory illness.

• Chest X-rays demonstrate pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

• Laboratory validation for the virus includes cell culture of SARS-CoV, detection of SARS-CoV ribonucleic acid by the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, or detection of serum antibodies to SARS-CoV. Detectable levels of antibodies may not be present until 21 days after the

onset of illness, but some individuals develop antibodies within 14 days. A negative PCR, antibody test, or cell culture doesn’t rule out the diagnosis.

onset of illness, but some individuals develop antibodies within 14 days. A negative PCR, antibody test, or cell culture doesn’t rule out the diagnosis.

TREATMENT

Treatment is symptomatic and supportive and includes maintenance of a patent airway and adequate nutrition. Other treatment measures include supplemental oxygen, chest physiotherapy, and mechanical ventilation. The recommended precautions for hospitalized patients include standard precautions, contact precautions requiring gowns and gloves for all patient contacts, and airborne precautions using a negative-pressure isolation room and properly fitted N-95 respirators. Quarantine can help prevent the spread of infection.

Patients who develop bacterial atypical pneumonia can receive antibiotics. Antiviral medications have also been used. High doses of corticosteroids may reduce lung inflammation. In some serious cases, patients have received serum from individuals who have already recovered from SARS (convalescent serum). The general benefit of convalescent serum treatment hasn’t been determined conclusively.

Drugs

• Beta-agonists such as albuterol (Proventil) for bronchospasm to relax bronchial smooth muscle

• Because SARS mimics bronchiolitis obliterans, steroids to reduce inflammation until diagnosis is differentiated (use is controversial)

• Combination of antiviral drugs normally used to treat acquired immunodeficiency syndrome—lopinavir plus ritonavir (Kaletra) along with ribavirin (Copegus)—to prevent serious complications and death (shown in clinical studies to be effective)

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Report suspected cases of SARS to local and national health organizations.

• Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs and respiratory status.

• Maintain isolation as recommended. The patient will need emotional support to deal with anxiety and fear related to the diagnosis of SARS and as a result of isolation.

• Provide patient and family teaching, including the importance of frequent hand washing, covering the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, and avoiding close personal contact while infected or potentially infected. Instruct the patient and his family that such items as eating utensils, towels, and bedding shouldn’t be shared until they have been washed with soap and hot water and that disposable gloves and household disinfectant should be used to clean any surface that may have been exposed to the patient’s body fluids.

• Emphasize the importance of the patient not going to work, school, or other public places, as recommended by the health care provider.

Silicosis

Silicosis is the term used for a lung disease that results from inorganic (minerals) and organic (small dust silica) crystal inhalation that’s not related to an allergic reaction. It’s a progressive disease characterized by nodular lesions that commonly progress to fibrosis. The most common form of pneumoconiosis, silicosis can be classified according to the severity of pulmonary disease and the rapidity of its onset and progression. It usually begins with breathlessness and sometimes weight loss; as it advances, the airways become obstructed and lungs become distorted by large, hard (calcified), nodular collagen masses.

Acute silicosis develops after 1 to 3 years in workers exposed to very high concentrations of respirable silica, such as sand blasters and tunnel workers. Accelerated silicosis appears after an average of 10 years of exposure to lower concentrations of free silica. Chronic silicosis develops after 20 or more years of exposure to still lower concentrations of free silica; chronic silicosis is further subdivided into simple and complicated forms.

The prognosis is generally good, unless the disease has progressed over the years into the complicated fibrotic form that involves all lobes and upper lung fields and produces such complications as hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, respiratory insufficiency, and cor pulmonale. Lung destruction is related to restriction, obstruction, and infections. Pulmonary disease may be malignant or nonmalignant; however, unlike asbestosis, silicosis doesn’t predispose a patient to cancer.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Silicosis results from the inhalation and pulmonary deposition of respirable crystalline silica dust, mostly from quartz, stone, sand, or flint. Silicosis can also develop from talc, vermiculites, and mica. The danger to the worker depends on the concentration of dust in the atmosphere, the percentage of respirable free silica particles in the dust, and the duration of exposure. Respirable particles are less than 10 microns in diameter, but the disease-causing particles deposited in the alveolar space are usually 1 to 3 microns in diameter. Silicosis severity is graded on the International Organization Scale based on size, shape, location, and profusion of the opacities. Confluent silicotic nodules destroy lung parenchyma, so the severest grading results in massive pulmonary fibrosis, which is indistinguishable from other forms of fibrotic lung disease.

Industrial sources of silica in its pure form include the manufacture of ceramics (flint) and building materials (sandstone). Silica occurs in mixed form in the production of construction materials (cement). It’s found in powder form (silica flour) in paints, porcelain, scouring soaps, and wood fillers as well as in the

mining of gold, coal, lead, zinc, and iron. Foundry workers, boiler scalers, and stonecutters are all exposed to silica dust and, therefore, are at high risk for developing silicosis.

mining of gold, coal, lead, zinc, and iron. Foundry workers, boiler scalers, and stonecutters are all exposed to silica dust and, therefore, are at high risk for developing silicosis.

Nodules result when alveolar macrophages ingest silica particles, which they’re unable to process. As a result, the macrophages release cytokines, proteolytic enzymes, tumor necrosing factor, and growth factor into surrounding tissue, stimulating the inflammatory response. The subsequent inflammation attracts other macrophages and fibroblasts into the region to produce fibrous tissue and wall off the reaction. The resulting nodule has an onionskin appearance when viewed under a microscope. Nodules develop adjacent to terminal and respiratory bronchioles, concentrate in the upper lobes, and are commonly accompanied by bullous changes in both lobes. If the disease process doesn’t progress, minimal physiologic disturbances and no disability occur. Occasionally, however, the fibrotic response accelerates, engulfing and destroying large areas of the lung (progressive massive fibrosis or conglomerate lesions). Fibrosis may continue even after exposure to dust has ended. Patients exposed to silica, even without silicosis, have three times the risk of developing tuberculosis (TB).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree