1 Routine Cardiac Evaluation in Children

Initial evaluation of children with possible cardiac problems includes (1) history taking, (2) physical examination, (3) electrocardiographic (ECG) evaluation, and (4) chest x-ray (CXR). The weight of information gained from these techniques varies with the type and severity of the disease.

I. HISTORY TAKING

Prenatal, perinatal, postnatal, past, and family histories should be obtained.

A. GESTATIONAL AND PERINATAL HISTORY

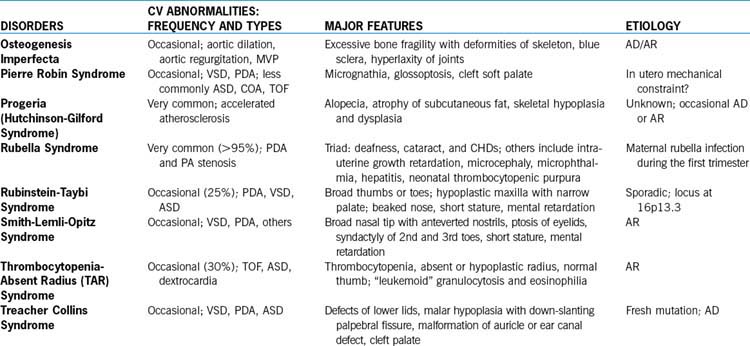

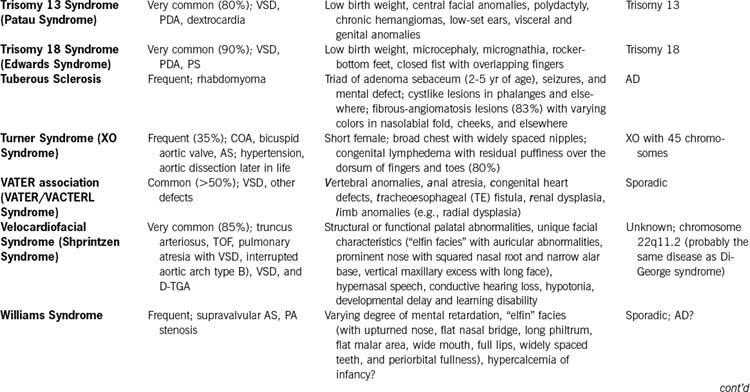

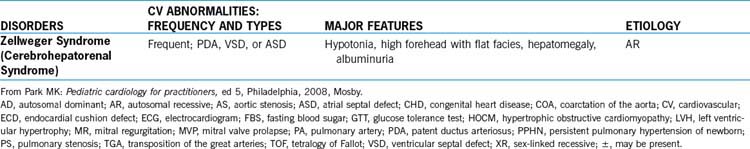

1. Maternal infection: Rubella during the first trimester of pregnancy commonly results in PDA and PA stenosis (rubella syndrome, Table 1-1). Other viral infections early in pregnancy may be teratogenic. Viral infections (including human immunodeficiency virus) in late pregnancy may cause myocarditis.

2. Maternal medications: The following is a partial list of suspected teratogenic drugs (with reported CHDs). Amphetamines (VSD, PDA, ASD, and TGA), phenytoin (PS, AS, COA, and PDA), trimethadione (fetal trimethadione syndrome: TGA, VSD, TOF, HLHS; see Table 1-1), lithium (Ebstein anomaly), retinoic acid (conotruncal anomalies), valproic acid (various noncyanotic defects), and progesterone or estrogen (VSD, TOF, and TGA) are highly suspected teratogens. Warfarin may cause fetal warfarin syndrome (TOF, VSD, and other features such as ear abnormalities, cleft lip or palate, and hypoplastic vertebrae; see Table 1-1). Excessive maternal alcohol intake may cause fetal alcohol syndrome (in which VSD, PDA, ASD, and TOF are common; see Table 1-1). Cigarette smoking causes intrauterine growth retardation but not CHD.

3. Maternal conditions: Maternal diabetes increases the incidence of CHD (TGA, VSD, and PDA) and cardiomyopathy (see Table 1-1). Both maternal lupus erythematosus and collagen diseases have been associated with congenital heart block in the offspring. History of maternal CHD may increase the prevalence of CHD in the offspring to as much as 15%, compared with 1% in the general population (see Appendix A, Table A-2).

B. POSTNATAL AND PRESENT HISTORY

1. Poor weight gain and delayed development may be caused by congestive heart failure (CHF), severe cyanosis, or general dysmorphic conditions. Weight is more affected than height.

2. Cyanosis, squatting, and cyanotic spells suggest TOF or other cyanotic CHD.

3. Tachycardia, tachypnea, and puffy eyelids are signs of CHF.

4. Frequent lower respiratory tract infections may be associated with large L-R shunt lesions.

5. Decreased exercise tolerance may be a sign of significant heart defects or ventricular dysfunction.

6. Heart murmur. The time of its first appearance is important. A heart murmur noted shortly after birth indicates a stenotic lesion (AS, PS). A heart murmur associated with large L-R shunt lesions (such as VSD or PDA) may be delayed. Appearance of a heart murmur in association with fever suggests an innocent murmur.

7. Chest pain. Ask if chest pain is exercise related or nonexertional; also ask about its duration, nature, and radiation. Nonexertional chest pain is unlikely to have cardiac causes. Cardiac causes of chest pain are usually associated with exertional pain and are very rare in children and adolescents. The three most common causes of nonexertional chest pain in children are costochondritis, trauma to chest wall or muscle strain, and respiratory diseases (see Child with Chest Pain in Chapter 6).

8. Palpitation may be caused by paroxysms of tachycardia, sinus tachycardia, single premature beats; rarely hyperthyroidism or mitral valve prolapse (MVP) (see Chapter 6).

9. Joint pain. Joints involved, presence of redness and swelling, history of trauma, duration and migratory or stationary nature of the pain, recent sore throat, rashes, family history of rheumatic fever, or the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis are important.

10. Neurologic symptoms. Stroke may result from embolization of thrombus from infective endocarditis, polycythemia, or uncorrected or partially corrected cyanotic CHD. Headache may be associated with polycythemia or, rarely, with hypertension. Choreic movement may result from rheumatic fever. Fainting or syncope may be due to vasovagal responses, arrhythmias, long QT syndrome, epilepsy, or other noncardiac conditions (see “Syncope” in Chapter 6).

11. Note medications, cardiac and noncardiac (name, dosage, timing, and duration).

12. Syndromes and diseases of other systems with associated cardiovascular abnormalities are summarized in Table 1-1.

C. FAMILY HISTORY

1. Certain hereditary diseases may be associated with varying frequency of cardiac anomalies (see Table 1-1).

2. CHD in the family. The incidence of CHD in the general population is about 1% (8 to 12 per 1000 live births). When one child is affected, the risk of recurrence in siblings is increased to about 3% (see Table A-1 in Appendix A). However, the risk of recurrence is related to the incidence of particular defects: Lesions with high prevalence (e.g., VSD) tend to have a high risk of recurrence, and those with low prevalence (e.g., tricuspid atresia, persistent truncus arteriosus) have a low risk of recurrence (see Appendix A, Table A-1). The probability of recurrence is substantially higher when the mother, rather than the father, is the affected parent (see Appendix A, Table A-2). Tables A-1 and A-2 can be used for counseling.

II. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A. INSPECTION

1. Assess general appearance: happy or cranky, nutritional state, respiratory status (tachypnea, dyspnea, or retraction may be signs of serious CHD), pallor (vasoconstriction from CHF or circulatory shock or severe anemia), and sweat on the forehead (seen in CHF).

2. Inspect for any known syndromes or conditions (see Table 1-1).

3. Malformations of other systems may be associated with varying frequency of CHD (Table 1-2).

4. Acanthosis nigricans (a dark pigmentation of skin crease on the neck) is often seen in obese children and those with type 2 diabetes and may signify the presence of hyperinsulinemia.

5. Precordial bulge, with or without actively visible cardiac activity, suggests chronic cardiac enlargement. Pectus excavatum may be a cause of a heart murmur. Pectus carinatum is usually not a result of cardiomegaly.

6. Cyanosis usually signals a serious CHD. A long-standing arterial desaturation (usually more than 6 months), even of a subclinical degree, results in clubbing of the fingers and toes.

TABLE 1-2 INCIDENCE OF ASSOCIATED CHDs IN PATIENTS WITH OTHER SYSTEM MALFORMATIONS

| ORGAN SYSTEM AND MALFORMATION | FREQUENCY (%) | SPECIFIC CARDIAC DEFECT |

|---|---|---|

| Central Nervous System | ||

| Hydrocephalus | 6 | VSD, ECD, TOF |

| Dandy-Walker syndrome | 3 | VSD |

| Agenesis of corpus callosum | 15 | No specific defect |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | 14 | No specific defect |

| Thoracic Cavity | ||

| TE fistula, esophageal atresia | 21 | VSD, ASD, TOF |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 11 | No specific defect |

| Gastrointestinal System | ||

| Duodenal atresia | 17 | No specific defect |

| Jejunal atresia | 5 | No specific defect |

| Anorectal anomalies | 22 | No specific defect |

| Imperforate anus | 12 | TOF, VSD |

| Ventral Wall | ||

| Omphalocele | 21 | No specific defect |

| Gastroschisis | 3 | No specific defect |

| Genitourinary System | ||

| Renal agenesis | ||

| Bilateral | 43 | No specific defect |

| Unilateral | 17 | No specific defect |

| Horseshoe kidney | 39 | No specific defect |

| Renal dysplasia | 5 | No specific defect |

ECD, endocardial cushion defect; TE, tracheoesophageal. Other abbreviations are listed on pp. xi-xii.

Adapted from Copel JA, Kleinman CS: Congenital heart disease and extracardiac anomalies: association and indications for fetal echocardiography, Am J Obstet Gynecol 154:1121–1132, 1986.

B. PALPATION

C. BLOOD PRESSURE

1. The following are currently recommended BP measurement techniques.

2. The normative BP standards recommended by the Working Group are not evidence based and are impractical for use by busy practitioners.

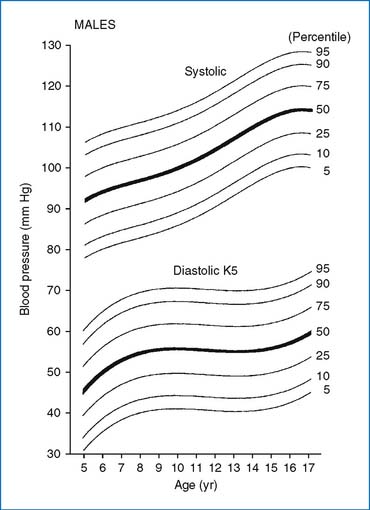

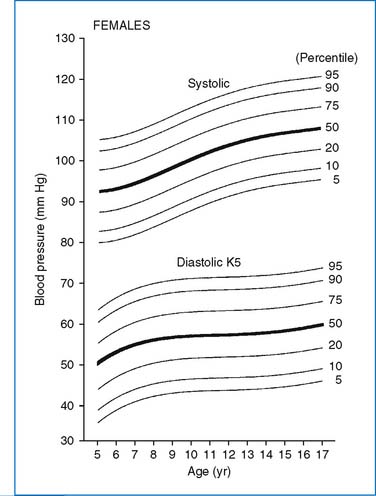

3. Normative percentile curves from the San Antonio study are the only standards obtained according to the currently recommended methodology, including that of the NHBPEP (Figs. 1-1 and 1-2). BP values are the averages of three readings. In using these percentile curves, one should consider the patient’s weight status before making the diagnosis of hypertension (BP levels ≥ 90th percentile). If the BP level is higher than the 90th percentile for the age and gender on three occasions, hypertension can be diagnosed, but the extent this abnormality is associated with weight should be considered before any presumption of organic disease is made. Percentile values of auscultatory systolic and diastolic pressures for children 5 to 17 years old are presented in Appendix B (Tables B-3 and B-4). Although BP standards recommended by the NHBPEP are unscientific, they are presented in Tables B-1 and B-2 for the sake of completeness.

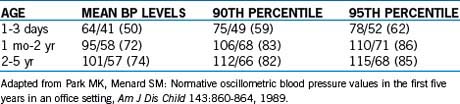

4. Oscillometric blood pressure values. It should be noted that BP readings by the auscultatory method and the currently popular oscillometric devices are not interchangeable. In the San Antonio Children’s Blood Pressure Study, BP measurements were obtained using both the auscultatory and Dinamap (model 8100) methods. BP levels obtained by the Dinamap were on average 10 mm Hg higher than levels obtained by the auscultatory method for the systolic pressure and 5 mm Hg higher for the diastolic pressure. Therefore, one should use different normative BP standards when BP is obtained by the Dinamap method. Dinamap-specific BP standards for children 5 through 17 years of age are presented in Tables B-5 and B-6. Normative BP standards by Dinamap for neonates and children up to 5 years of age are presented in Table 1-3.

5. The following are additional comments regarding BP measurements in children and adolescents.

FIG. 1-1 Age-specific percentile curves of auscultatory systolic and diastolic (K5) pressures in boys 5 to 17 years of age. BP values are the averages of three readings. The width of the BP cuff was 40% to 50% of the circumference of the arm. The percentile values for the graph are shown in Appendix B,.

(From Park MK, Menard SW, Yuan C: Comparison of blood pressure in children from three ethnic groups, Am J Cardiol 87:1305–1308, 2001.)

FIG. 1-2 Age-specific percentile curves of auscultatory systolic and diastolic (K5) pressures in girls 5 to 17 years of age. BP values are the averages of three readings. The width of the BP cuff was 40% to 50% of the circumference of the arm. The percentile values for the graph are shown in Appendix B, Table B-4.

(From Park MK, Menard SW, Yuan C: Comparison of blood pressure in children from three ethnic groups, Am J Cardiol 87:1305–1308, 2001.)

TABLE 1-3 NORMATIVE BLOOD PRESSURE LEVELS [SYSTOLIC/DIASTOLIC (MEAN)] (IN MM HG) BY DINAMAP MONITOR (MODEL 1846 SX) IN CHILDREN UP TO AGE 5 YEARS

D. AUSCULTATION

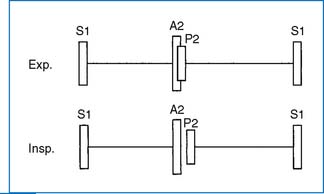

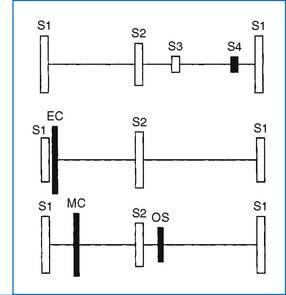

2. Systolic and diastolic sounds

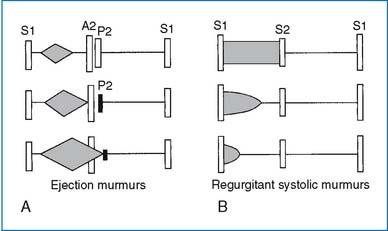

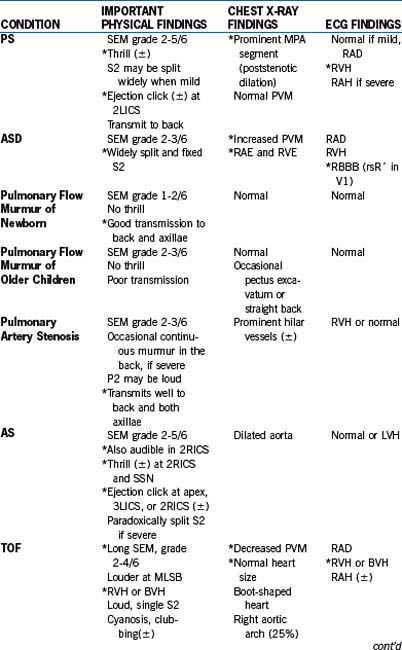

3. Heart murmur. Each heart murmur should be analyzed in terms of intensity, timing (systolic or diastolic), location, transmission, and quality (e.g., musical, vibratory, blowing).