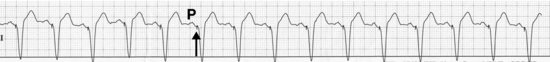

Normal sinus rhythm, atrial sensed and ventricular paced

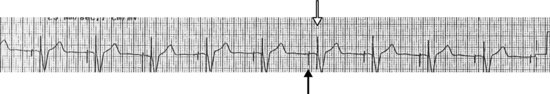

Atrioventricular (AV) paced rhythm

DESCRIPTION

Although technically not an arrhythmia, it is probably worthwhile learning to recognize when a pacemaker is present, since paced rhythms can sometimes look like real arrhythmias. This is sort of like including azaleas in a wildflower book: although technically a shrub, azalea flowers do look like wildflowers, and … well, you get the idea. Although pacemaker manufacturers have been adding features at a dizzying rate, the basic functioning of a pacemaker hasn’t changed much.

A pacemaker will have a lead in the right ventricle, and may also have a lead in the right atrium. We’re not going to discuss biventricular pacemakers or defibrillators. Each lead will usually sense the spontaneous heart rate in its chamber. If the underlying heart rate in that chamber is faster than what the pacemaker is set to (usually 60 or 70), the pacemaker will do nothing except “listen.” But if the pacemaker detects a pause in the rhythm, or if the rate in its chamber slows below what it is set to, the device will send an electrical impulse down the appropriate lead to stimulate its chamber and keep the heart rate from falling below what it is set to. That’s simple enough, isn’t it? Maybe … but if not there’s an army of pacemaker field engineers and representatives, not to mention electrophysiologists (who some will tell you prefer looking at rhythm strips to talking to patients) around who will be happy to explain this to you if you ask nicely. A proffering, such as a cup of coffee and/or a doughnut, will definitely help.

The key to looking at an ECG with pacemaker activity is first to recognize if there is actual pacemaker activity. Remember that if the underlying heart rate is faster than what the pacemaker is programmed to, there will be NO pacemaker activity, and there is no way you can tell there is a pacemaker present just by looking at the ECG. When the pacemaker is actually pacing you can see a little spike (the electrical impulse fired by the pacemaker) either just before the P wave if there is atrial pacing (the paced P wave will look fairly normal), or before the QRS, if there is ventricular pacing. If there is ventricular pacing the QRS will NOT look normal if it is stimulated by a pacemaker impulse; it will be wide and have a left bundle branch block appearance (ask an electrophysiologist why this is so). The pacer spikes may not be obvious in all leads, and may be pretty small in some of them, so you may need your reading glasses if you’re over 40.

In our samples, the first one shows just ventricular pacing (solid arrows), with P waves marching right through (open arrows) with no relation to the V-paced rhythm. Just like complete heart block, right? It actually is complete heart block, except here the pacemaker is providing the escape rhythm instead of an unreliable (and usually very slow) junctional or idioventricular escape rhythm! The ventricle in this example is the only chamber with a pacemaker lead. If you wanted to be a wise guy you could point out that the patient could also have an atrial lead which may be broken and just not working.

In our second example, the underlying rhythm is still sinus, but now every P wave is followed by a V-paced beat. Unless this is an incredible coincidence (which it is not), this means that each P wave (creatively marked “P”) is sensed by a lead in the right atrium, which, after the appropriate delay, is followed by a pacemaker spike delivered to the right ventricle (see arrow); this maintains normal AV synchrony and is better for the patient as you might imagine. This ability to pace and sense both chambers is the hallmark of the dual-chamber pacemaker.

In the third example, both the atrium (solid arrow) and ventricle (open arrow) are paced. Here it is obvious there are two leads involved. I should let you know there is an arcane and highly complex mainly three-letter code which is used by pacemaker reps and electrophysiologists which describes how many pacemaker leads there are and how they function.1 If you think there is only one lead, call it a VVI device, and if there are two leads, call it a DDD device. With those two terms even if you know nothing else about pacemakers most people will think you are an expert and leave you alone.

HABITAT

Pacemaker rhythms may be found wherever older folks are placed on monitors, although young ‘uns might wind up with pacemakers too. If the patient you’re visiting has a bulge under his or her left clavicle, as long as you’ve ensured it’s not a gun in a shoulder holster, then it’s likely it’s a pacing device of some sort.

CALL

“I think the patient is in VT but the rate is 70!”

RESEMBLANCE TO OTHER ARRHYTHMIAS

The most common error when one sees the wide complex beats of a paced rhythm is thinking it’s a ventricular rhythm and panicking. First (as usual!) check the patient! If he or she is OK, then go back to the monitor. If the rate is 60 or 70, the usual rates pacemakers are programmed to, look closely before the P waves or QRS complexes in all leads and see if you can pick out pacemaker spikes. Of course the patient could be in a sinus rhythm with a bundle branch block without a pacemaker. Look to see if there are P waves in front of each ventricular paced beat. If a P wave precedes every ventricular paced beat this has to be a dual chamber pacemaker, with the device keeping the ventricular contraction in synch with the spontaneous sinus rhythm. The pacemaker will follow the atrial rate and pace the ventricle as high as 120; with atrial rates above 120 the pacemaker will do all sorts of funky things but won’t pace the ventricle faster than 120 (the most common upper rate limit for pacemakers).

CARE AND FEEDING

Pacemakers generally do just fine with a check of the battery and maybe a little “tweak” of its programming every few months. I’m told there are now 109 permutations of programming options (give or take a few powers of 10), which is enough to keep even the most obsessive electrophysiologist busy for a while. If you ever see pacemaker spikes with no P or QRS following (depending on which chamber is supposed to be paced) ask someone to come check the device, especially if it was just implanted – maybe a lead came loose. And if you see pacemaker spikes where you shouldn’t (such as closely following a QRS which should have been sensed) then call somebody also. The worst they can do is tell you it was just artifact and not a pacemaker spike.

How can you tell if a pacemaker is present if it isn’t pacing because the intrinsic heart rate is too fast? Well, you can examine the patient’s chest for an unnatural foreign object implanted below a clavicle. A chest X-ray will also give it away and show you how many leads are present as a bonus. And there is a trick involving a special magnet (NOT to be tried by yourself, just like you are not supposed to try all those cool stunts performed by professional drivers on closed tracks) that an electrophysiologist or pacemaker field representative can show you, which will not only demonstrate that a pacemaker is present, but will also prove it is actually functional.

1 Bernstein AD, Daubert JC, Fletcher RD, et al. The revised NASPE/BPEG generic code for antibradycardia, adaptive-rate, and multisite pacing. North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology/British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25(2):260–4.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree