Retrograde Ilio-SMA and Celiac Bypass

James McPhee

Thomas N. Carruthers

Indications

Patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) tend to present to surgeons later in the course of their disease, after extensive diagnostic workup for other causes of abdominal pain. Classic symptoms include postprandial crampy abdominal pain, diarrhea (+/− heme), sitophobia or “food fear,” and otherwise unexplained weight loss. While incidental findings on CT scan of extensive calcification of the celiac artery or superior mesenteric artery (SMA) are common, further workup should be prompted by the presence or absence of symptoms. The hemodynamic significance of calcific lesions can be assessed by mesenteric duplex ultrasound. Other diagnostic modalities include CT angiography and formal angiogram. Once the diagnosis of CMI is made, barring prohibitive risk, intervention is typically offered due to the risk of progression to acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) and attendant mortality rate. Many of these patients will be treated with endovascular angioplasty and stenting of the affected arteries. However, in cases where endovascular treatment is unsuccessful, technically not feasible, or if disease recurs in or around the stented segment, open surgical approaches should be considered.

For patients presenting with AMI, our preference is to proceed directly to open revascularization, as this approach allows for direct assessment of bowel viability and resection if necessary. AMI as a result of embolic disease may be treated with thrombectomy alone, whereas those cases that are consequent to preexisting CMI often require surgical bypass.

Two approaches to open mesenteric revascularization via bypass (as opposed to endarterectomy or transposition) are antegrade and retrograde. Antegrade bypass, covered in detail in Chapter 12, has the advantage of a more anatomical course and consequently less chance of graft kinking when compared to retrograde bypasses. Additionally, the supraceliac aorta tends to have less calcific disease compared to the distal abdominal aorta and iliac arteries. Antegrade techniques require more extensive dissection, supraceliac aortic clamping, and often a retropancreatic tunnel for the graft limb to the SMA. In contrast, retrograde bypass can be done with straightforward infrarenal aortic or iliac

artery exposure, may be accomplished without aortic cross-clamping (in the cases of iliac inflow), and may be accomplished relatively quickly.

artery exposure, may be accomplished without aortic cross-clamping (in the cases of iliac inflow), and may be accomplished relatively quickly.

Contraindications

The risk associated with open mesenteric revascularization is substantial and standard preoperative risk stratification should be performed. Many of these patients have the added insult of chronic malnutrition which has postoperative healing implications. Other considerations include prior abdominal operations, radiation therapy, or extensive calcific disease of the donor inflow vessels that may preclude safe clamping or anastomosis creation. A distinct contraindication would be the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm or iliac aneurysm in the proposed inflow region. We would favor antegrade reconstruction in cases where the presence of even a small aneurysm in the infrarenal aortoiliac segment may need future reconstruction.

A full history and physical exam is an essential starting point for operative planning. Specific attention to other cardiovascular symptoms such as angina, exertional dyspnea, and the like may have implications on the approach chosen for mesenteric revascularization. A thorough peripheral pulse exam can determine presence of occlusive disease in other beds. Any history of prior abdominal or vascular operations should be elicited from the patient or the medical record. The patient will often have had extensive workup prior to reaching the diagnosis of CMI, including endoscopy, colonoscopy, and imaging studies. These should be reviewed by the surgeon prior to any operation to avoid ordering duplicate tests.

Noninvasive studies such as ankle brachial indices/pulse volume recording (ABI/PVR) should be performed if the physical exam suggests occlusive lower extremity vascular disease. Significant suprainguinal disease, when detected, may prompt further abdominal vascular imaging and can influence the choice of inflow. If there is concern for bowel viability then vein mapping (including the femoral veins) should be performed to determine if any appropriate autogenous conduit is present in either leg. Mesenteric duplex may be performed to document the hemodynamic extent of the detected occlusive disease and may establish an important baseline if patients are to be followed in this manner postoperatively.

Preoperative cardiology assessment is standard in our institution; however, in the absence of active coronary symptoms or heart failure, medical optimization should be relatively rapid and should not needlessly delay mesenteric revascularization.

Our standard is to perform a preoperative CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis with fine 1- to 3-mm cuts. This allows the surgeon to closely examine not only the arterial system, including any aneurysmal disease or aberrant anatomy, but also the venous system, solid organs, and intestines. The degree of calcification of the distal aorta and common iliac arteries (CIAs) can give the surgeon some idea of which vessel will provide the best inflow. Many patients may have undergone antecedent endovascular interventions and while angiographic images obtained may be useful to guide bypass target choice, CT scan provided invaluable information as well.

Patients should be instructed to perform a chlorhexidine shower the night before surgery. We generally do not recommend a bowel prep, as this may disadvantage the patient in terms of preoperative dehydration and increased resuscitation requirements intra- and postoperatively. Patients should receive prophylactic weight-based doses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics within an hour of incision. We prefer to use cefazolin in patients who do not have a penicillin allergy. We add vancomycin if synthetic graft is to be used, which is the majority of cases. Cefazolin is redosed every 4 hours intraoperatively, vancomycin every 6 hours. A nasogastric (NG) tube is placed at the beginning of the operation and left in place until return of bowel function. A Foley catheter is inserted for accurate measurement of urine output during and after the operation. An

arterial line is placed both for hemodynamic management and monitoring of activated clotting times (ACT) during systemic heparinization. A central line for fluid resuscitation and central venous pressure monitoring may be considered, but at the very least, two large-bore peripheral IV catheters should be placed.

arterial line is placed both for hemodynamic management and monitoring of activated clotting times (ACT) during systemic heparinization. A central line for fluid resuscitation and central venous pressure monitoring may be considered, but at the very least, two large-bore peripheral IV catheters should be placed.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with the arms out, and is secured to the table with a safety strap around the chest, above the nipples. All bony prominences are padded in these often thin patients, and the Foley is passed beneath the patient’s leg, with padding to protect the posterior thigh. The lower extremities are placed in a frog-leg position to aid in potential dissection of the GSV. The area to be prepped is predraped with clear plastic adhesive drapes, including one to exclude the genitalia. The patient is prepped from nipple to knees, first with a chlorhexidine scrub, then after drying, a chlorhexidine–alcohol solution. The prep is allowed to dry for at least 3 minutes, and the previously placed clear adhesive dressings are covered with sterile towels. A half-sheet is placed over the lower legs, and another over the upper chest. The prepped area is then carefully covered with an adhesive antimicrobial drape. A split-sheet drape is then applied to the lower half of the field and a top-drape is secured to supports at the head of the table.

Technique

A midline incision is made from the xiphoid process to the pubis to the left of the umbilicus. The linea alba is identified and carefully divided along the length of the incision. The peritoneum is identified through the preperitoneal fat, grasped with DeBakey forceps, and divided sharply. Once the peritoneal cavity is entered, the peritoneum is divided over the operator’s finger with electrocautery to protect the intra-abdominal contents. Any adhesions are carefully dissected using a combination of Metzenbaum scissors and electrocautery. The abdomen is explored for any evidence of malignancy, and the stomach is palpated to ensure appropriate placement of the NG tube. The stomach, small bowel, and colon are inspected for any signs of ischemic damage. Though uncommon in elective operations, the presence of ischemic bowel injury would strongly influence the choice of conduit material. If there is suspicion of peritoneal contamination, the surgeon or an assistant will go about harvesting autogenous conduit, usually the GSV.

A self-retaining retractor system is then set up. The choice of specific retractor system is based on surgeon preference, but we prefer the Vascular Omni-Flex System for its versatility and wide range of retractor blades. The small bowel is eviscerated to the patient’s right, a moist laparotomy pad is wrapped high on the root of the mesentery, and the now protected viscera is returned to the right side of the abdomen and held in place with a wide malleable slotted blade.

Selection and Exposure of Inflow

The options for inflow for a retrograde bypass to the mesenteric vessels are the distal abdominal aorta, right CIA, or left CIA. Additionally, the external iliac vessels are an acceptable inflow source if calcific burden precludes safe clamp placement on a more proximal source. Typically, the proximal right CIA affords the most advantageous lie of the graft for a smooth C loop up to the SMA. The choice is based on the degree of atherosclerotic and calcific disease as determined by preoperative imaging, noninvasive studies, and intraoperative findings. Aneurysmal disease in any of these potential inflow sites would preclude their use.

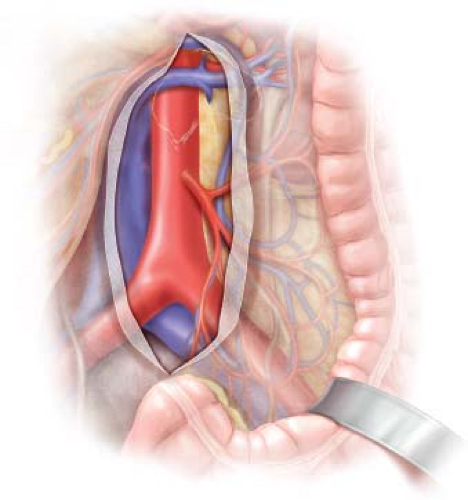

The abdominal aorta and bilateral CIA are palpated to corroborate preoperative imaging findings and to evaluate for any unexpected pathology. Exposure of the aorta and iliac vessels proceeds in a standard fashion, akin to that for aneurysmorrhaphy (Fig. 13.1). The

retroperitoneum is incised slightly to the right of midline over the distal abdominal aorta to avoid injury to the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Liberal ligation and division of retroperitoneal fat and lymphatic tissue will minimize the risk of postoperative lymphatic leakage. Large collaterals to the SMA distribution from the internal iliac system may be encountered, and should be preserved. The division of the retroperitoneum is carried down to the level of the aortic bifurcation, and then extended down the preferred iliac artery chosen for inflow. As the dissection approaches the iliac bifurcation, the ureter is typically swept to the right with the retroperitoneal tissue. Knowledge of the location of the ureter should be maintained to protect it from injury, during the dissection itself, positioning of the retractors, or during ultimate clamping of the iliac artery. If the left iliac artery is selected for inflow attention should be paid to the nervi erigentes that cross the left CIA, specifically in men to avoid the potential for postoperative retrograde ejaculation. Circumferential control of the aorta or iliac artery is generally not necessary, and may be dangerous, leading to injury of posterior venous structures. Likewise separate exposure and control of the external iliac and hypogastric are not routinely necessary unless the area of anastomosis is going to encompass the distal CIA or the bifurcation.

retroperitoneum is incised slightly to the right of midline over the distal abdominal aorta to avoid injury to the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Liberal ligation and division of retroperitoneal fat and lymphatic tissue will minimize the risk of postoperative lymphatic leakage. Large collaterals to the SMA distribution from the internal iliac system may be encountered, and should be preserved. The division of the retroperitoneum is carried down to the level of the aortic bifurcation, and then extended down the preferred iliac artery chosen for inflow. As the dissection approaches the iliac bifurcation, the ureter is typically swept to the right with the retroperitoneal tissue. Knowledge of the location of the ureter should be maintained to protect it from injury, during the dissection itself, positioning of the retractors, or during ultimate clamping of the iliac artery. If the left iliac artery is selected for inflow attention should be paid to the nervi erigentes that cross the left CIA, specifically in men to avoid the potential for postoperative retrograde ejaculation. Circumferential control of the aorta or iliac artery is generally not necessary, and may be dangerous, leading to injury of posterior venous structures. Likewise separate exposure and control of the external iliac and hypogastric are not routinely necessary unless the area of anastomosis is going to encompass the distal CIA or the bifurcation.

When adequate exposure has been obtained, clamps are selected and test-fit to provide maximal exposure during creation of the proximal anastomosis. We find Wylie hypogastric clamps or short soft-jaw Fogarty clamps distally minimize clamp interference while sewing. Proximal iliac artery clamping can also be performed with a similar technique. In the infrarenal aortic segment we find side-biting aortic clamps to be unnecessarily cumbersome and offer little benefit.

Exposure of Outflow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree