TABLE 6.1 Essential Criteria for Diagnosis of Restless Legs Syndrome | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 6.2 Restless Legs Syndrome Criteria in Children | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

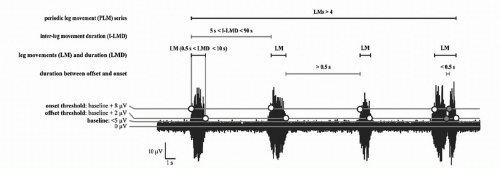

The diagnostic criteria for PLMS are used to calculate the PLMS index, which represents the number of periodic limb movements per hour.

The PLMS index indicates the clinical severity of PLMS. According to the guidelines set by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) (4), a PLMS index of greater than 15 in adults and greater than 5 in children is considered clinically significant.

Any PLMS index below 15 in adults is not clinically significant, because they can be frequently encountered in the general population and do not usually result in sleep complaints or excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) (5). Table 6.3 shows the criteria used to assess PLMS on a PSG. Figure 6.1 visually demonstrates the scoring criteria for a periodic limb movement series.

TABLE 6.3 Criteria Used to Indicate a Periodic Leg Movements as per the AASM Scoring Manual | ||

|---|---|---|

|

movements when resting in the evening or before sleep onset without any related uncomfortable sensations or urge to move the legs (12).

TABLE 6.4 Additional Characteristics Unique to Restless Leg Syndrome in Relation to the Four Diagnostic Criteria | |

|---|---|

|

that the diagnostic criteria are not met and therefore the RLS diagnosis cannot be made. Th is will then prompt further evaluation for other etiologies on the differential.

TABLE 6.5 Tools/Supportive Features for Accurate Restless Leg Syndrome Diagnosis beyond the Essential Criteria | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 6.6 Differential Diagnosis for Restless Leg Syndrome (including Restless Leg Syndrome Mimics) | |

|---|---|

|

(Table 6.8). For instance, 48% of patients with low-density lipoprotein have RLS (14) and approximately 21% of RLS sufferers have concurrent diabetes (15).

TABLE 6.7 Potential Aggravators | |

|---|---|

|

TABLE 6.8 Serum Evaluation for Restless Legs Syndrome | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The SIT has been developed in the research setting to serve as a measure of RLS severity and to assist in the diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity of RLS utilizing the SIT is 81%, and 81%, respectively, with a PLMW index of greater than 40 on the SIT (18). When combined with a traditional PSG, the specificity and sensitivity of the test reaches 82% and 100%, respectively, making this test an effective tool for diagnosis (16).

TABLE 6.9 Conditions Associated with Periodic Leg Movements of Sleep

Narcolepsy

REM sleep behavior disorder

Neurodegenerative disorders

Tourette’s syndrome

Peripheral neuropathy

Rheumatological disorders

End-stage renal disease

Pregnancy

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Sleep apnea

Antidepressants (exceptions: bupropion, trazodone)

Moderate dementiaa

a In a study performed on older adults with early to moderate dementia and nighttime sleep disturbance, the most common risk factors for RLS symptoms were a PLMS index >15, based on PSG, and use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (9) .

The significance of excessive leg movements—whether demonstrated by PSG, leg activity meters, or SIT—must always be considered within in the clinical context of the patient’s presentation. As shown in Table 6.9, PLMS are very nonspecific findings and can be found as a normal variant of age as well as in association with a variety of medical, neurologic, and primary sleep disorders (19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree