Fig. 47.1

(a) Weblike postintubation stenosis with preserved cartilage. Laser resection may be successful; however, recurrence is likely to occur; (b) hourglass-like postintubation stenosis with destruction of all layers. Segmental resection indicated (Reprinted with permission from Heberer et al. editors. Lunge und mediastinum, Springer; 1991, Fig. 18.58)

Fig. 47.2

Weblike postintubation stenosis 2.5 cm below the vocal cords, endoscopic aspect

Clinic/Symptoms

As stenoses, apart from granulations, generally develop slowly, they are often not diagnosed until at an advanced stage. Therefore, many patients have adapted to high-degree obstruction. Only when the diameter is reduced to 5–6 mm does a significant drop in the peak flow appear.

Patients with pertinent postintubation stenoses have dyspnea on exertion or dyspnea at rest with noticeable stridor. These patients are often mistaken for asthma sufferers, particularly when the X-ray image does not indicate any abnormalities. Inspiratory stridor usually indicates a fixed stenosis or malacia of the cervical trachea, whereas intrathoracic lesions are accompanied by expiratory stridor.

Diagnosis

It should be clarified with every patient exhibiting stridor after recent intubation whether a scar stenosis can be excluded. A thoracic CT scan with 3-D reconstruction provides an overview of the degree and extension of the stenosis, permitting an evaluation of operability and reconstruction planning with the exposition of an intact trachea. A flexible tracheoscopy should confirm the findings; however, it can be postponed until the time of operation if there is a clear indication to operate and convincing images are available. High-degree scar stenoses that require emergency intervention may be removed with a rigid bronchoscopy, or a tracheostomy with possible subsequent resection may be necessary to safeguard the airways. Should a malacic lesion – which may also result from cuff damage – be suspected primarily, then an endoscopy ought to be done with spontaneous respiration. Systemic lesions like Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, tuberculosis, or amyloidosis may involve the trachea and induce diffuse narrowing. These patients should undergo systemic treatment. Only rarely a segmental resection may become necessary.

Acute Obstruction

An endoscopy should be performed in case of acute obstruction by a postintubation stenosis, ideally using a jet ventilation catheter. The introduction of a rigid endoscope to the point of the stenosis is followed by suctioning secretions and subsequent cautious dilatation of the constriction by sliding forward the dilatator with increasing diameter or the rigid bronchoscope itself. The dilatation is to be effected with rotating movements to avoid a rupture of the usually less rigid posterior wall. If an instrument the size of at least 3 mm can be introduced, then sufficient lumen width has been achieved for the moment to be able to plan an elective operation. Should this not be feasible, then a tracheotomy must be performed in the case of a cervical lesion, ideally on the level of the stenosis. Airway stenting may be a preliminary option if the patient’s condition does not allow for a subsequent surgical procedure. In our opinion, the use of laser is contraindicated as it causes even more scars and strictures. Solely in case of very short, weblike strictures or when predominantly granulation tissue constricts the lumen, can a bougienage or removal by laser provide permanent success. All in all, the less time that passes after the triggering trauma, the greater the chances are of a permanent correction.

Surgical Principles

The definitive therapy of a fixed or postintubation stenosis, which has been repeatedly dilatated without success, is surgical resection and end-to-end reconstruction, the same being valid for stenoses in connection with a tracheostoma. Reconstruction can be performed in an emergency if circumstances require this. A delay of the operation is advisable if there are significant inflammatory changes, if the patient cannot be withdrawn from the respirator, or if the necessary cooperation on the part of the patient cannot be anticipated for other reasons.

Practically all postintubation stenoses can be treated surgically with success if they are operated on in the primary instance and do not initially undergo repeated conservative measures. If short, softened sections in combination with a stenosis occur, these will be integrated into the resection. Longer, softened segments have to be treated with a stent, T-tube, or external stabilization, depending on the functional significance.

Access to the upper two-thirds of the trachea is achieved through a collar incision which is extended caudally by a median incision to the upper border of the manubrium.

If a tracheostoma is to be removed at the same time, the incision takes place at the level of the stoma. A partial sternotomy can follow if needed. The lower third of the trachea may be reached equally well through a complete sternotomy or a right-sided thoracotomy in the third or fourth intercostal space. The preparation of the trachea must be effected along the immediate wall contours so as not to endanger the Nn. recurrentes. An exposition of the nerves should be refrained from any case in view of the benign processes. With transsternal access, the supra-aortic branches may not be exposed out of their connective tissue, as this might otherwise promote arrosion bleeding.

The size and extent of the constriction must be determined exactly with the endoscope because the extension of the lesion cannot always be reliably determined intraoperatively. In this case, the upper and lower end of the lesion must be marked under endoscopic control with an aspiration needle. After installing the jet ventilation catheter, a transection is performed, at the lower end in the case of cranial stenoses and at the upper end in the case of caudal stenoses, and mobilization out of the environment is carried out with visual control to the other end of the stenosis. The circumferential dissection of the trachea at the proximal and distal border of the defect should not exceed 1 cm in order not to endanger the blood circulation of the anastomosis. After affixing a stay suture on the distal stump, mobilization with a cranial pull is performed and the loose connective tissue ventral to the trachea down to the bifurcation is severed or pushed aside. Now the patient’s head is ventrally flexed by the anesthetist and fixed in this position with pillows. In this way, defects of up to 5 cm can be bridged without danger. Running sutures are placed along the posterior wall with PDS 4/0 (Ethicon, USA); however, the adaptation is not yet fully completed to avoid ripping of the sutures. Only when the corner sutures have been inserted and with a pull on the stay sutures will the edges of the posterior wall be adapted and the running sutures of the posterior wall connected to the corner sutures. All interrupted sutures for the anterior wall are placed and tied one after another. Before this, blood coagulation and secretions should be removed once again from the bronchial system and the transition from jet ventilation to ventilation with the tracheal tube prepared. In no case may the tube cuff be placed at the level of the anastomosis. A leakage test is obligatory. For this purpose, ventilation pressure of 30 cm H2O is built up while the operational field undergoes rinsing with a saline solution. Early extubation of the patient is desired. Tracheal release maneuvers are special techniques that permit a reduction of anastomotic tension. The aforementioned dissection of the pretracheal compartment down to the bifurcation and ventral head flexion is obligatory. Only in very rare cases is a hilar or laryngeal release maneuver applied.

Results

In the greatest published series of postintubation stenoses and resection including reconstruction (Grillo, Pearson), good or very good results for over 90% of the patients were achieved. Mortality ranged from approximately 2% to 4%; morbidity (anastomosis insufficiency, infection, restenosis) is estimated at 4–10%. In addition to the surgeon’s expertise, several different factors influencing complication rates have been determined:

(a)

Every surgical pretreatment significantly aggravates the operation and results in twice the number of cases of mortality. This substantiates the requirement that a competent surgeon should perform the initial operation.

(b)

The safest anastomoses are those with an end-to-end connection in the tracheal section. Anastomosis with the cricoid cartilage is riskier with respect to healing, whereby connections between the trachea and thyroid bear even greater risks.

(c)

A contraindication for resection is present with patients under ventilation for a long period of time.

Postoperative problems such as vocal ligament palsy, intralaryngeal swelling, or an edema of the anastomosis may require an immediate or delayed tracheotomy. This is preferably performed below the anastomosis but must be securely covered by a muscle flap with respect to the truncus brachiocephalicus to avoid vascular arrosion.

Restenoses at the level of the anastomosis are rare when expert techniques are employed, absorbable stitching material is used, and the complete resection of the diseased segment is performed. The prophylaxis for stenoses caused by intubation is the correct use of large-volume cuffs. Pertinent complications after a tracheotomy can be avoided if mechanical irritations between the tube and trachea entrance are reduced to a minimum.

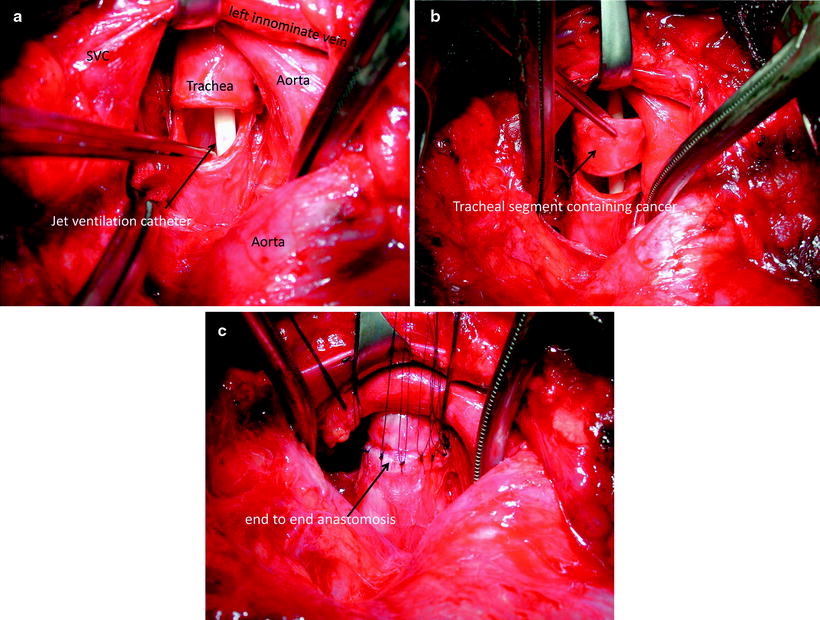

Tumors of the Trachea

Adenoid cystic carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are the most frequent primary malignant tumors of the trachea, the former often including the main carina. Carcinoids, mucoepidermoid tumors, small cell carcinomas, lymphomas, or benign chondromas are rare. Leading among secondary tumors are carcinomas of the thyroid gland, which often include the subglottic area and the cricoid (refer to Chap. 51). Allowing for the size of the tumor, the best choice of therapy is a tracheal segmental resection (exception: small cell carcinomas, lymphomas) with end-to-end reconstruction (refer to Fig. 47.3a–c). The adenoid cystic carcinoma typically progresses beyond visible limits by spreading submucosally or paratracheally within the perineural lymphatics. In this case, intraoperative specimen examinations are indispensable. The security of the anastomosis, i.e., a tension-free reconstruction, always has priority over microscopically free resection borders, as the tumor occasionally grows very slowly. For this reason, excessive resection focussing solely on radicality is to be avoided.