Repair of Congenital Defects: Morgagni Diaphragmatic Hernia

Scott A. Anderson

Mike K. Chen

DEFINITION

A Morgagni congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) refers to a defect in the anteromedial diaphragm through the foramen of Morgagni. The most common contents of the hernia include omentum and transverse colon but can also include stomach, liver, spleen, and other segments of bowel. Morgagni hernias more commonly include a hernia sac.

They account for approximately 3% of surgically repaired diaphragmatic hernias. They are more frequently seen in females and the majority of them are right-sided. Bilateral Morgagni hernias can be seen but are not common.

Unlike Bochdalek CDHs, Morgagni hernias are generally not associated with pulmonary hypoplasia. They are typically smaller and more frequently an isolated congenital anomaly.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morgagni CDH can be mistaken for a number of other thoracic anomalies, both congenital and acquired. In infancy, these can include congenital cystic lung disease, esophageal hiatal hernia, and mediastinal mass.

Later in life, Morgagni hernia can be confused with a mediastinal mass, pericardial fat pad, atelectasis, pneumonia, or a pleural abscess.

The various imaging and diagnostic studies used to distinguish among these are mentioned in a subsequent section.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The diagnosis of a Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia can sometimes be a long and winding road. Neonates do not frequently arrive with the diagnosis already made by prenatal imaging, as is often the case with Bochdalek CDH. The signs and symptoms of Morgagni hernias are also usually nonspecific. Likewise, routine radiologic imaging can also overlook the more subtle defects. Because of this, Morgagni hernias are sometimes not diagnosed until later in life.

The most common presentation in neonates and infants is an increased work of breathing or respiratory distress. Many, however, are relatively asymptomatic. Children may present with a history of recurrent chest infections. Teenagers and adults can present with any variety of symptoms including dyspnea, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and constipation or they may be completely asymptomatic. Predisposing conditions, such as chronic cough, trauma, pregnancy, and obesity, can contribute to the likelihood of symptomatic presentation.

The physical examination is most commonly normal. However, distant heart tones and unequal breath sounds may be present. In cases of strangulation or volvulus, the patient may demonstrate significant abdominal tenderness and signs of shock. A detailed physical examination is always indicated in newborns to assess for congenital abnormalities.

Although most commonly isolated, Morgagni hernias can be associated with congenital heart disease, malrotation, and Down’s syndrome.1 The workup should include an echocardiogram when the diagnosis is made in infancy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Morgagni hernias are not frequently detected on prenatal imaging.

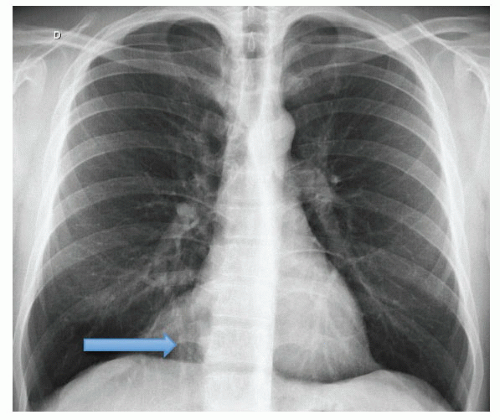

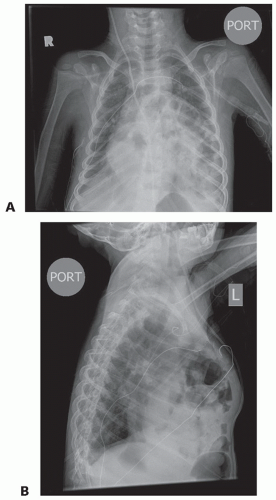

A posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiograph is the initial diagnostic study of choice. This can have different appearances depending on the contents within the hernia. It may show airfilled loops of bowel projecting over the anterior mediastinum (FIG 1A,B) or a well-defined opacity in the right cardiophrenic angle (FIG 2). The latter, however, is not very specific.

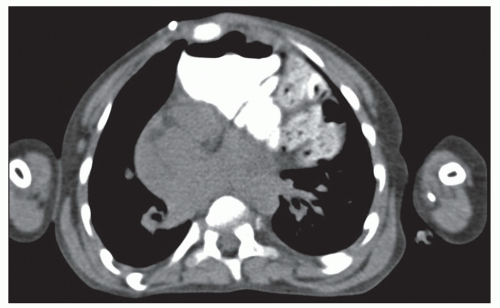

The diagnosis can be more readily made on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (FIG 3).

Ultrasound, barium enema, and upper gastrointestinal (GI) series also can be a useful part of the diagnostic workup.

Diagnostic thoracoscopy or laparoscopy is recommended if the diagnosis remains unclear after appropriate imaging studies.

FIG 1 • PA (A) and lateral (B) chest x-ray demonstrating airfilled loops of bowel in the anterior mediastinum consistent with a Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia. |

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

In general, elective repair of Morgagni hernias is recommended to prevent future complications such as incarceration, strangulation, or volvulus.

Morgagni diaphragmatic hernias can be successfully repaired through either transabdominal or transthoracic approach using open or minimally invasive techniques. We tend to favor the transabdominal approach when feasible because it allows for better visualization of the central diaphragm and for detection of bilateral hernias that may not be clearly seen on preoperative imaging. Laparoscopy is generally well tolerated in infants, even those with congenital heart disease.2

In infants, who can present with respiratory distress, lung protective strategies are initiated. When a ventilator is required, spontaneous respiration and permissive hypercapnia are used. Surgery is then performed on an elective basis, once medically stable, prior to discharge.

For the patients with Morgagni hernias that present with acute incarceration, strangulation, or volvulus, immediate surgical management is indicated. Appropriate resuscitative measures should be initiated prior to surgery.

Prior to taking the patient to the operating room, all diagnostic studies should be thoroughly reviewed and the patient appropriately marked on the affected side.

Ensure that the airway is secure and the endotracheal tube is in a stable position. Pre- and postductal oxygen saturation monitoring is maintained in neonates to assess for signs of right-to-left shunting.

OPEN MORGAGNI HERNIA REPAIR

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position on the operating room table (FIG 4).

Sterile plastic drapes are used as a barrier over the patient outside of the operative field. A warming blanket is also used to maintain temperature stability.

Incision

A transverse, subcostal incision is made one to two fingerbreadths below the costal margin. An incision made too close to the costal margin can make for a more difficult repair and subsequent fascial closure. An upper midline incision may also be used.

The abdominal wall muscle and fascia are divided and the peritoneum entered.

Exposure of the Defect and Hernia Reduction

The falciform ligament of the liver is taken down off the abdominal wall and the left lateral segment mobilized if needed.

The liver is carefully retracted away from the diaphragm to expose the posterior and lateral boundary of the diaphragmatic hernia defect (FIG 5).

The abdominal contents within the hernia are carefully reduced and returned to the abdomen.

A hernia sac, when present, is excised with electrocautery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree