FIGURE 21-1 Tortuous brachiocephalic in a 92-year-old woman.

Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Elderly Patients versus Younger Patients

Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

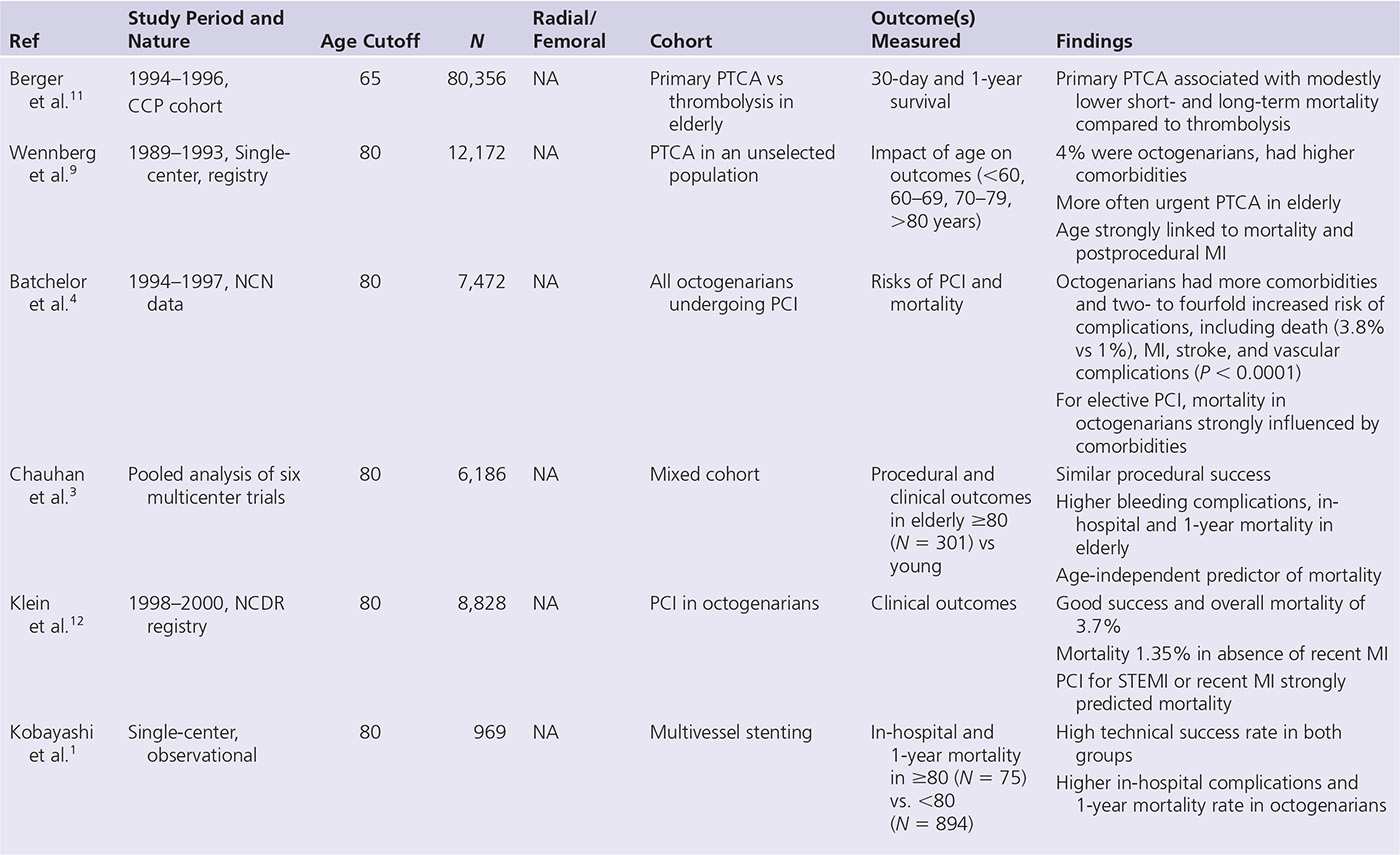

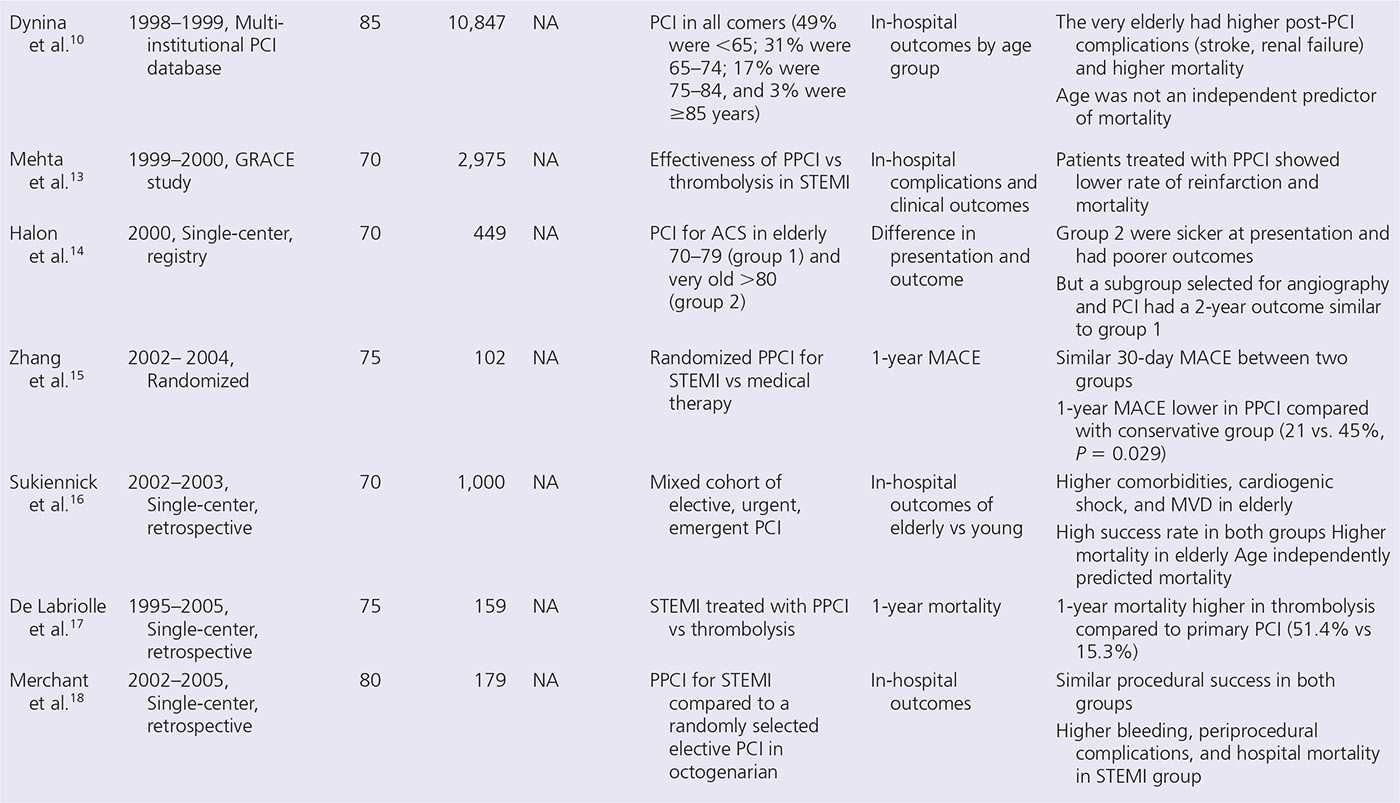

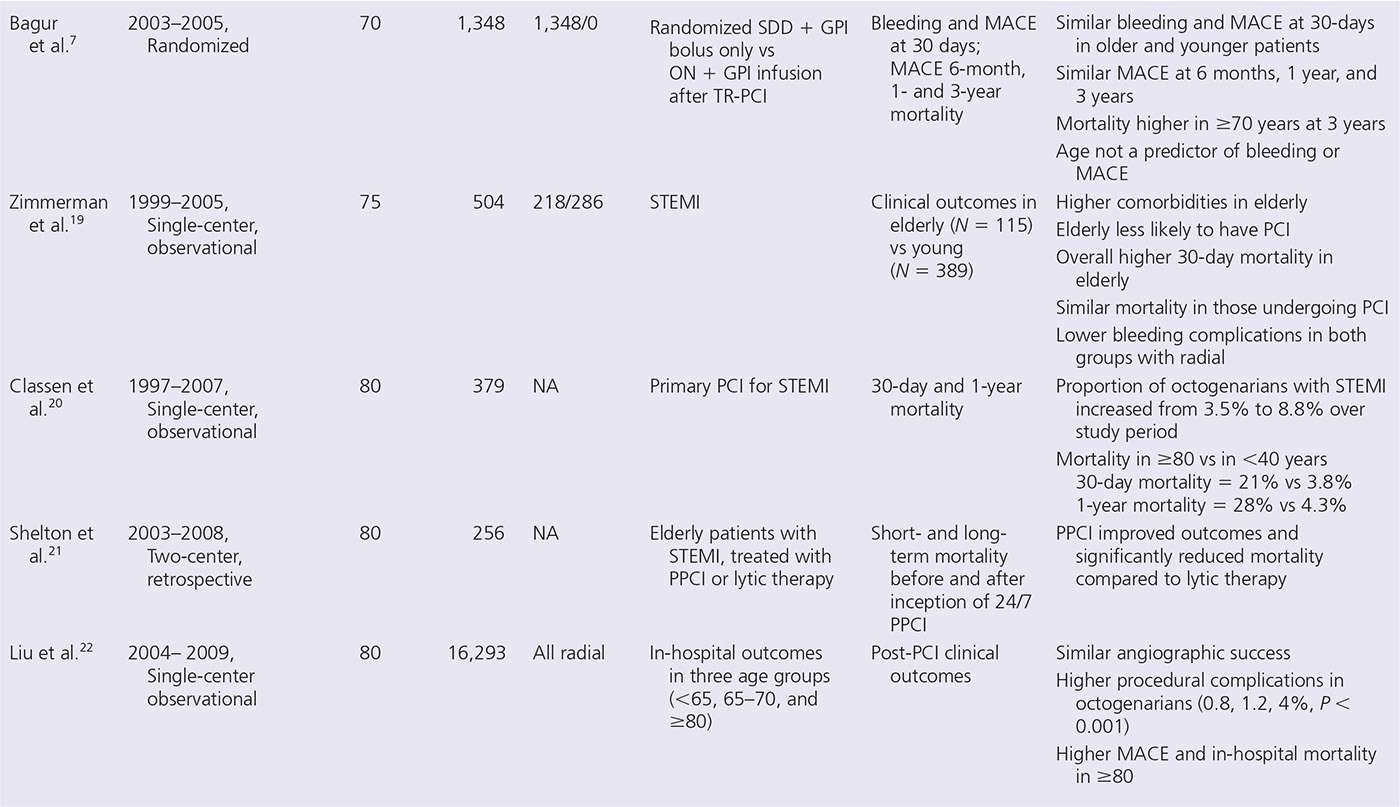

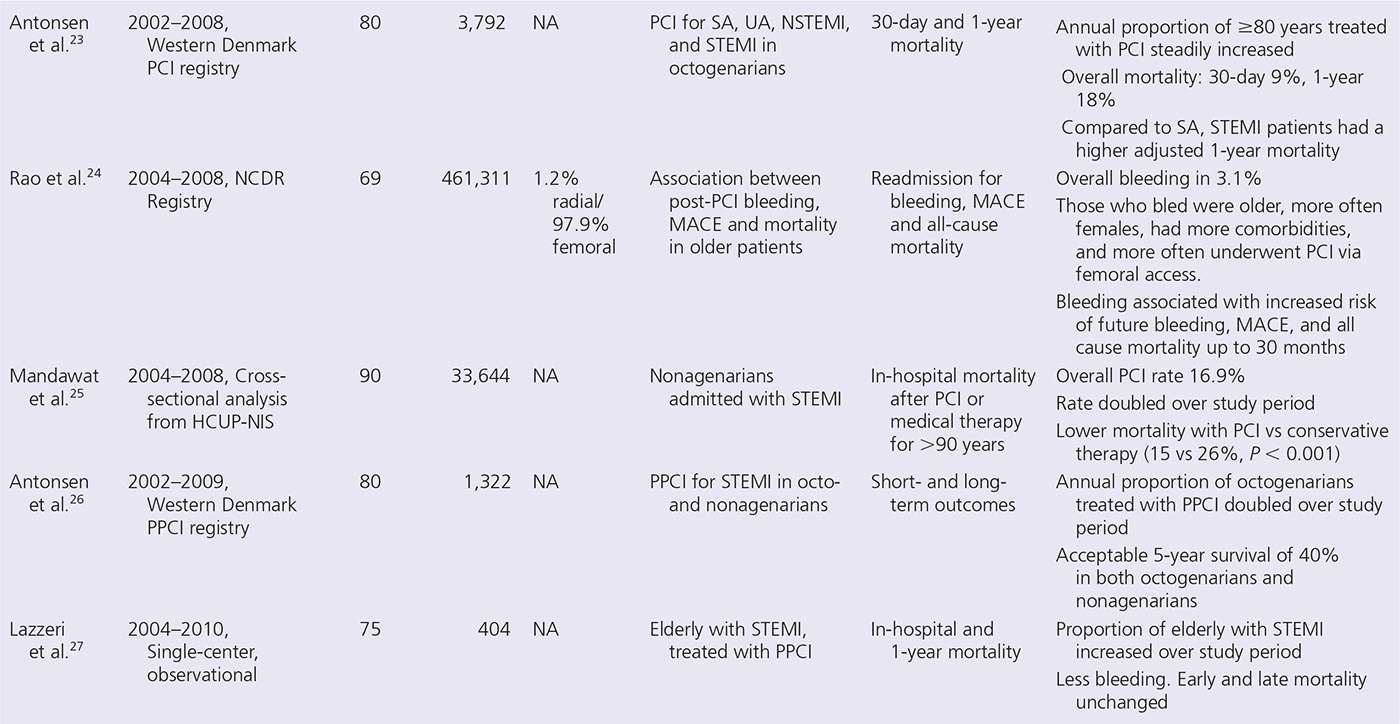

The decision to proceed with PCI in elderly patients is often influenced by multiple factors, including baseline functional and mental status and comorbidities. Elderly individuals presenting with coronary artery disease often have more advanced atherosclerotic vascular disease and adverse coronary morphologies, including tortuosity and calcification. Observational studies and registries of elderly patients undergoing elective PCI have shown lower rates of procedural success and higher rates of complications, including recurrent myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, vascular complications, renal failure, and in-hospital mortality4,9,10 (Table 21-1).

TABLE 21-1 Trends and Outcomes of PCI in Elderly Patients: Elective, ACS, and STEMI

CCP, Cooperative Cardiovascular Project; GPI, glycoprotein inhibitor; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HCUP-NIS, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MVD, multivessel disease; NCDR, National Cardiovascular Database Registry; NCN, National Cardiovascular Network; ON, overnight stay; PPCI, primary PCI; SA, stable angina; SDD, same-day discharge; TR-PCI, transradial PCI; UA, unstable angina.

Batchelor et al.4 compared in-hospital outcomes of 7,472 octogenarians (mean age, 83 years) with those of 102,236 young patients (mean age, 62 years), who underwent PCI at 22 National Cardiovascular Network database hospitals between 1994 and 1997. Octogenarians had more comorbidities, and a two- to fourfold increased risk of complications, including death (3.2% vs 1.1%), MI (1.9 vs 1.3), renal failure (3.2% vs 1%), and vascular complications (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). Mortality demonstrated a curvilinear relation with age, ranging from approximately 0.5% for patients <50 years old to 5% in <85 years. Age <85 years was an independent predictor of procedural mortality. For elective PCI, mortality in octogenarians was strongly influenced by the presence of comorbidities (0.79% with no risk to 7.2% with renal insufficiency and left ventricular ejection fraction < 35%). A subsequent report from the ACC-NCDR from 1998 to 2000 found that octogenarians undergoing PCI had high success rates and acceptable mortality rates,12 with higher mortality in patients with acute or recent MI.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndromes

Elderly individuals represent the fastest growing segment of the population, are increasingly referred for PCI, and are at higher risk of both bleeding as well as thrombotic events.28–31 Patients ≥75 years represent 10% of those who have had MI, but account for 25% of all hospital deaths.32 Nonetheless, limited data are available on the safety of PCI in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or ST-elevation MI (STEMI), as these are often underrepresented in randomized trials.33,34 Several single-center observational and registry studies have examined the outcomes in elderly patients with ACS and STEMI treated with PCI (Table 21-1).

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Non-ST-Segment Elevation MI

The impact of advanced age on management, antithrombotic strategies, and clinical outcomes of ACS has been previously documented.35,36 In an observation from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE),35 involving 24,165 patients in 102 hospitals across 14 countries stratified by age, it was found that elderly patients ≥65 years had more comorbidities, showed longer delay in seeking medical attention, and were least likely to undergo invasive treatment. Older patients were more likely to present with non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI) than were younger patients.35 Major bleeding rates were significantly higher with increasing age (>6% in ≥85 vs 2%–3% in <65 years; P = <0.0001). In-hospital mortality, adjusted for baseline characteristics, also steadily increased across age strata (odds ratio [OR]: 15.7 in patients ≥85 years, compared to <45 years).35

In a prespecified analysis of ACUITY trial (N = 13,819) of 30-day and 1-year outcomes across four age groups (<55, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years), patients aged ≥75 years represented 17.7% of study population.36 Both ischemic and bleeding complications after NSTEMI significantly increased with age. Patients who received bivalirudin alone had similar ischemic outcomes, but significantly lower bleeding complications than did those treated with heparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.36 However, femoral access was used for the majority of these patients. The role of bivalirudin in reducing major bleeding in patients undergoing radial procedures remains uncertain.37,38

Few data exist on the use of radial access in PCI for ACS in the elderly. The EASY (Early Discharge After Stenting of Coronary Arteries) trial7 compared clinical outcomes between patients ≥70 and <70 years who underwent PCI exclusively via transradial access. Patients were randomized to either same-day discharge and abciximab bolus only or overnight hospitalization and bolus, followed by 12-hour infusion of abciximab, after uncomplicated transradial stenting.7 Among the 1,348 patients enrolled in the trial, 259 (19%) were aged ≥70 years. At 30 days, the rates of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events) and major bleeding were similar in older and younger patients.7 This provided a reassuring signal that the reduction in major bleeding with radial access in elderly patients is similar to that in younger patients, even when potent antithrombotic and antiplatelet agents are utilized.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment Elevation MI

Although primary PCI, combined with antithrombotic therapy, has substantially reduced morbidity and mortality associated with acute MI,39 mortality rates in the elderly undergoing primary PCI for STEMI remain substantially higher than in younger patients.12 Attempts to improve outcomes with more potent antithrombotic therapy are hampered by higher rates of periprocedural bleeding.40 Furthermore, limited data are available on the safety of PCI in elderly patients with STEMI, because of underrepresentation of elderly patients in the randomized trials.33

Despite these shortcomings and worse outcomes, several studies have shown that elderly patients derive incrementally more benefit from primary PCI than from thrombolytic therapy.11,41 In a recent meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials evaluating primary PCI versus thrombolytic therapy,41 the reduction in clinical end points seen with primary PCI was not influenced by age. As such, age per se should not be an exclusion criterion for the application of primary PCI.

The use of bleeding avoidance strategies in 10,469 patients aged ≥80 years with STEMI undergoing primary PCI in an NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) study was shown to be suboptimal.42 The use of vascular closure devices for femoral access, combined with direct thrombin inhibitors, increased over the study period (2006–2009); however, radial access was rarely used (<1%) in this age group.42

Radial Access in Elderly Patients versus Younger Patients

Radial Artery Size

The inner radial artery diameter, measured 1 to 2 cm proximal to the styloid process, is approximately 2.45 to 2.7 mm in the majority of individuals (2.69 in men and 2.43 in women),43 and can therefore accommodate 6F catheters or larger. The mean radial diameter correlates significantly with body surface area.43 In a small proportion of individuals (particularly in the elderly, females, and diabetics), it tends to be smaller in caliber. There has been no study that has specifically examined the radial diameter in the elderly population.

Tortuosity and Calcification

Elderly patients are more likely to have considerable brachiocephalic and subclavian tortuosities and advanced vascular disease. In addition, elderly subjects have a higher frequency of unfolding of the aorta and aortic root dilatation. This twists the origin of aortic arch into a posterior position, which may impede wire and catheter entry into the ascending aorta.44 This difficulty can often be overcome with certain maneuvers such as deep inspiration to straighten the mediastinum and realign the aortic brachiocephalic trunk, allowing catheter entry and manipulation into the ascending aorta.44 In addition to subclavian tortuosity, radial and brachial tortuosities are also more common with increasing age, as demonstrated by a two-dimensional ultrasound study of 1,191 patients undergoing transradial catheterization.43

The combination of diffuse atherosclerotic disease of the great vessels, tortuosity, calcification, and more complex coronary anatomy in elderly patients poses a particular challenge for transradial operators, particularly during the early phase of the learning curve. Not surprisingly, advanced age has been shown to independently predict failure of transradial approach to PCI.45

Right versus Left Radial Access

Despite the many advantages in favor of radial over femoral access, operators wanting to adopt the radial approach remain unclear as to which radial is better. Comparison between right and left radial accesses has, in fact, been the subject of several observational and a few randomized trials.46–53 Such studies predominantly focused on procedural time, success rate, crossover, and radiation exposure, often with conflicting results, and as such, whether one site is superior to the other remains controversial.

A recent meta-analysis54 pooled data from five randomized trials comparing right versus left radial access for diagnostic and interventional coronary procedures. Neither right nor left radial was significantly better than the other in terms of procedural duration, fluoroscopy time, contrast volume, or incidence of complications. However, left radial access was associated with significantly less need for crossover to the femoral approach (3.1 vs 5.2%, RR = 1.65; P = 0.003) compared to right radial.54

It is not clear whether this 2% absolute reduction in risk of access site failure with left radial is due to potential anatomical advantage with left radial, differences in operator experience, or both. It has been suggested that the left radial access provides a more natural transition into the ascending aorta, ensuring similar catheter maneuverability to that of femoral access. Some have even advocated that inexperienced operators should preferentially use left radial to minimize failure.46 Although plausible, it remains to be proven in an adequately powered randomized trial. Until such a trial is completed, there appears to be no additional advantage to adopting the left radial access routinely, at least in the hands of an experienced operator. Indeed, in a recent international survey of transradial practice,55 approximately 90% of operators stated that they routinely used right radial as default access.

In the only randomized trial of right versus left radial access that focused exclusively on elderly patients (octogenarians, N = 100),56 both approaches were similar in procedural and fluoroscopy times. Subclavian tortuosity (as reported by the operator) was more frequent on the right than on the left side (32% vs 10%, respectively; P = 0.002); however, this did not translate into significantly different crossover rate.56 In fact, there were numerically more crossovers with left (10%) than with right radial (4%), although this did not reach a statistical difference (P = 0.24).56

Radial versus Femoral Access in Elderly Patients

Observational Studies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree