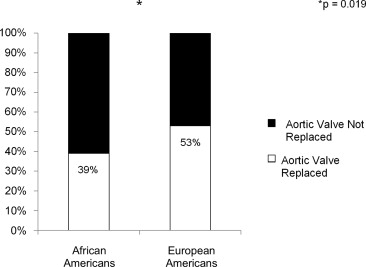

Racial disparities exist in the treatment of many cardiovascular diseases. Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is the only treatment for aortic stenosis (AS) that improves patient symptoms and survival. To date, no studies have compared the rate of AVR among different races. The records of patients with an aortic valve area <1 cm 2 by echocardiography diagnosed between January 2004 and May 2010 at Barnes-Jewish Hospital were reviewed retrospectively. Patients were stratified by race. Of the 880 patients analyzed, 10% were African American (AA), and 90% were European American (EA). AA more frequently had hypertension (82% vs 67%, p <0.01), diabetes mellitus (45% vs 32%, p = 0.02), chronic kidney disease (28% vs 17%, p = 0.01), and end stage renal disease (18% vs 2%, p <0.001). AA underwent AVR less frequently than EA (39% vs 53%, p = 0.02) and refused intervention more often (33% vs 20%, p = 0.04). When treated, AA and EA had similar 3-year survival (49% [38 to 60] vs 50% [45 to 54], p = 0.31). Identification of the factors associated with treatment refusal would further our ability to counsel patients on the decision to pursue AVR.

The influence of race on the rate of aortic valve replacement (AVR) has not been evaluated thoroughly. Several studies have shown that African Americans (AA) undergo invasive procedures such as joint replacement, lung cancer resection, and intervention for acute myocardial infarction less frequently than European Americans (EA) ; however, the role of race in forgoing AVR has not been previously investigated. We conducted a study with the following aims: (1) to determine if AA with severe aortic stenosis (AS) underwent AVR less frequently than EA with severe AS and (2) to identify the reasons for this disparity, if present.

Methods

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, a large university-based academic tertiary referral center with a 36.7% AA patient population. The local echocardiographic database was queried to identify patients with severe AS (defined as an aortic valve area <1.0 cm 2 ) from studies performed between January 2004 and December 2010. Patients were excluded from analysis if insufficient medical data were available after the echocardiogram (n = 19), if the patient was of a race other than EA or AA, was younger than 18 years, was undergoing repeat AVR, or was undergoing AVR for reasons other than AS. Non-AA/non-EA accounted for <1% (n = 5) of the total sample and were excluded for analysis because of the small sample size. The Institutional Review Board of Washington University in St. Louis reviewed and approved the study protocol.

For patients with an echocardiogram revealing severe AS, electronic medical records were reviewed. Demographic characteristics and past medical and surgical history were recorded. Laboratory data and medication use was analyzed. Special attention was paid to documentation of symptoms potentially attributable to AS, including angina pectoris or other chest pain, presyncope or syncope, and dyspnea, edema, fatigue, or other evidence of heart failure.

Echocardiographic and Doppler parameters were collected. Severe AS was defined as a calculated aortic valve area <1.0 cm 2 . Other parameters of interest included mean and peak aortic valve gradient, left ventricular systolic dysfunction as measured by an ejection fraction ≤50%, right ventricular dysfunction as defined by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion <1.5 cm, and pulmonary systolic artery pressure >25 mm Hg. Severity of mitral regurgitation was determined qualitatively with Doppler echocardiography.

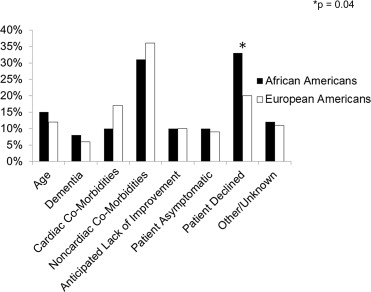

Evaluation by a cardiothoracic surgeon and treatment received (i.e., balloon aortic valvuloplasty or AVR) were assessed and recorded. For patients who did not undergo surgery, the rationale, when available, was categorized into (1) advanced age (if mentioned in medical record), (2) clinical diagnosis of dementia, (3) cardiac comorbidities (such as ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy), (4) noncardiac comorbidities (such as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, or active malignant neoplasm), (5) anticipated lack of symptomatic improvement with AVR, (6) lack of patient symptoms, (7) patient declination, or (8) other/unknown (if the patient was lost to follow-up, died before evaluation for AVR was completed, or if reasons for not undergoing AVR were never explicitly stated). If the patient was deceased at the time of analysis, the date of death was recorded as found in the U.S. Social Security Death Index.

Data for categorical variables are reported as number and percentages; comparisons between groups were made using Fisher’s exact test (when the expected value in any of the cells was ≤5). Continuous variables with normal distributions are reported as mean ± SD; comparisons between groups of continuous variables with normal distribution were made using unpaired Student’s t tests (2-tailed). Comparisons between groups of continuous variables with nonnormal distribution were made using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U tests. Survival was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method; comparison between groups was made using log-rank test. For all analyses, symptomatic status was defined at the time of echocardiography or AVR; subsequent development of symptoms was not tracked. Patients were considered to have had no intervention if no AVR was performed at Barnes-Jewish Hospital after diagnosis of severe AS or if no note in the medical record mentioned that AVR was performed at another facility after the diagnosis of severe AS at the time of chart review. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of 0.05. Statistical analysis for this paper was performed using Version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

During the study period, 907 patients with severe AS by transthoracic echocardiography were identified. Of these, 880 had known treatment status; analysis was limited to these patients. Among these 880 patients, 791 were EA (90%), and 89 were AA (10%).

AA with severe AS were more frequently women and more often had other cardiac and noncardiac co-morbidities ( Table 1 ). Overall, rates of symptomatic AS were similar between races; however, EA more frequently complained of dyspnea than did AA ( Table 1 ). AA had evidence of worse disease severity by echocardiographic parameters compared with EA ( Table 2 ).

| Overall (n = 880) | AA (n = 89) | EA (n = 791) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 76 ± 12.6 | 77.5 ± 12.2 | 75.9 ± 12.6 | 0.27 |

| Men | 54% | 37% | 56% | 0.004 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 28.2 ± 7 | 27.5 ± 6.1 | 28.3 ± 7.1 | 0.33 |

| Hypertension (chart history) | 69% | 82% | 67% | 0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33% | 45% | 32% | 0.017 |

| Coronary artery disease (chart history) | 48% | 46% | 48% | 0.74 |

| Heart failure | 30% | 41% | 28% | 0.019 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 18% | 28% | 17% | 0.014 |

| End-stage renal disease | 4% | 18% | 2% | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 29% | 21% | 30% | 0.11 |

| Dyslipidemia (chart history) | 54% | 47% | 55% | 0.18 |

| Smoker | 48% | 41% | 48% | 0.25 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Symptomatic | 86% | 82% | 86% | 0.33 |

| Angina pectoris | 25% | 27% | 24% | 0.59 |

| Dyspnea | 73% | 62% | 74% | 0.02 |

| Syncope | 9% | 8% | 9% | 1.00 |

| Overall (n = 880) | AA (n = 89) | EA (n = 791) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication use | ||||

| Aspirin | 60% | 57% | 60% | 0.65 |

| Clopidogrel | 12% | 18% | 12% | 0.08 |

| Digoxin | 11% | 5% | 12% | 0.046 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 39% | 43% | 38% | 0.49 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 11% | 15% | 10% | 0.20 |

| Beta blockers | 53% | 54% | 53% | 0.91 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 25% | 34% | 24% | 0.05 |

| Statins | 52% | 55% | 52% | 0.65 |

| Warfarin | 21% | 11% | 22% | 0.026 |

| Bisphosphonates | 5% | 0% | 6% | 0.017 |

| Calcium | 13% | 7% | 14% | 0.07 |

| Phosphate binders | 2% | 14% | 1% | <.001 |

| Laboratory variables | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.49 ± 2.8 | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 1.4 ± 2.9 | <.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 27 ± 17 | 29 ± 18 | 27 ± 17 | 0.16 |

| Total calcium (mg/dl) | 9.25 ± 0.77 | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 0.08 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.89 ± 2.25 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 2.4 | 0.011 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 144 ± 52 | 160 ± 50 | 142 ± 52 | 0.008 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 114 ± 78 | 95 ± 47 | 116 ± 81 | 0.003 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 43 ± 16 | 53 ± 18 | 42 ± 16 | <.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 77 ± 35 | 89 ± 40 | 76 ± 34 | 0.004 |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 52 ± 15 | 48 ± 16 | 52 ± 14 | 0.031 |

| Aortic valve area (cm 2 ) | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.13 |

| Mean gradient (mm Hg) | 38 ± 14 | 34 ± 13 | 38 ± 14 | 0.007 |

| Peak gradient (mm Hg) | 64 ± 23 | 61 ± 28 | 64 ± 22 | 0.35 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 44 ± 15 | 50 ± 16 | 44 ± 15 | 0.002 |

| Mitral regurgitation severity | 0.28 | |||

| None | 25% | 22% | 25% | |

| Mild | 58% | 54% | 58% | |

| Moderate | 14% | 18% | 14% | |

| Severe | 3% | 6% | 3% | |

| Right ventricular dysfunction | 13% | 25% | 11% | <.001 |

During the study period, 51% of patients diagnosed with severe AS underwent AVR. AA underwent AVR significantly less frequently than did EA ( Figure 1 ). Additionally, AA more frequently declined intervention than did EA; otherwise, reasons for not undergoing AVR were similar between the 2 groups ( Figure 2 ). When controlling for renal dysfunction, racial differences in the rate of AVR remained significant (odds ratio 0.55, 95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.87, p = 0.01).

The presence of medical insurance did not affect the rate of AVR between races because frequency of coverage was identical between the 2 groups. Medicare coverage was similar; however, Medicaid was more commonly used by AA, whereas more EA had private insurance ( Table 3 ).