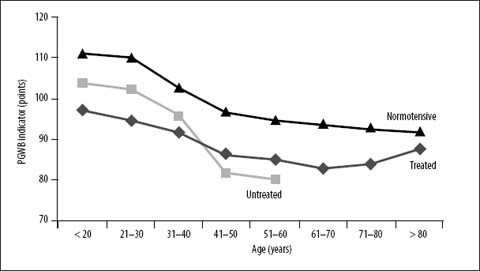

Fig. 2.1

Quality of Life measured with the Psychological General Wellbeing Index in hypertensive (n = 1539) and normotensive subjects (n = 995) according to age. Reproduced from [15], with permission

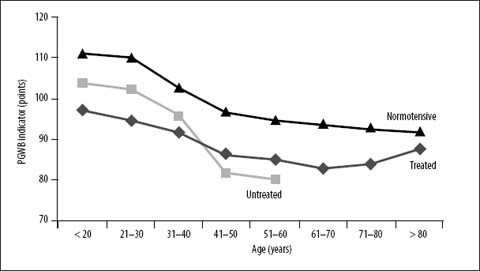

For the reasons mentioned above, some researchers have suggested that a reduction in the HRQoL of subjects with hypertension may be because they were diagnosed with a disease (so-called “labeling effect”). Mena-Martin et al. [14] demonstrated that subjects who were aware of being hypertensive had a poorer QoL than those who were not aware. A reduction in HRQoL is further associated with anxiety, depression, worrying about one’s health, physical functioning, absenteeism from work, and can even influence the lives of family members [18]. This effect — even before introducing pharmacotherapy — certainly reduces HRQoL in those diagnosed with hypertension [14]. Considering the risk of even further reductions in HRQoL, such patients require added attention during treatment. It was believed previously that the labeling effect had a significant role only in the early stages after the diagnosis. However, data showed that it may have a significant role for a few years, thereby negatively influencing an already declining HRQoL [19]. An already decreased HRQoL in untreated hypertensive individuals (as well as in individuals with undiagnosed hypertension) and the fact that individuals with chronic hypertension have a lower HRQoL than individuals with “white-coat hypertension” (which is diagnosed when BP is consistently > 140/90 mmHg in the office or clinical setting but is normal, < 135/85 mmHg, with ambulatory or home BP monitoring) [20], indicates that the labeling effect may not be the only factor influencing decreased HRQoL in hypertensive patients. Studies undertaken in Poland [15, 17] confirmed that, in complementary age groups, the general HRQoL of individuals being treated and not being treated by pharmacological means for hypertension was lower than that of the healthy population (Fig. 2.2). In this study, individuals aged < 40 years not yet treated for hypertension had a significantly greater HRQoL than subjects of the same age undergoing treatment (Fig. 2.2). Recently, Trevisol et al. found (in a population study of > 1,850 individuals; mean age, 47 years (men) and 52 years (women)) that HRQoL assessed with the SF-12 was worse in subjects with hypertension (in men and women) treated by pharmacological means when compared with untreated patients [21]. The lower HRQoL of hypertensive subjects was independent of age and education. Moreover, scores for women were lower than in men for all the SF-12 domains independent of the diagnosis of hypertension [22]. The findings of these studies suggest that a worse perception of wellbeing during treatment with antihypertensive drugs may cause problems with adherence to treatment in the future (especially in relatively young patients with a high HRQoL at baseline).

Conversely, data collected from multicenter studies suggest that untreated individuals may also have some degree of cognitive, psychomotor, and/or sensory dysfunction which may normalize after treatment. Thus, impaired HRQoL in hypertensive patients might be secondary to the awareness of hypertension, the adverse effects of drugs, or the presence of concomitant diseases, and not high BP per se [23].

Fig. 2.2

Age-based comparison of Quality of Life (Psychological General Wellbeing Index) in treated (n = 1271) and untreated (n = 268) hypertensive subjects compared with normotensive controls (n = 995). Reproduced from [15], with permission

The HRQoL of women with hypertension is lower than that in men of the same age [13, 15, 22]. Analogous differences between the sexes can also be observed in the general (healthy) population. However, the reasons for these differences are incompletely understood. In studies of hypertensive subjects in Poland [15, 17] decreases in the HRQoL of women during their fertile years were found to be attributed to reduced vitality and increased anxiety. During menopause, in addition to these two factors, reduced HRQoL was attributed to worsening health. In women aged > 60 years, HRQoL was affected by worsening health, amplified depression, and a feeling that “control was lost over their lives”. These results were similar to those of other studies which examined significantly worsening HRQoL in older hypertensive women [13].

The Alameda County study was a 20-year follow-up study examining the psychosocial indicators of hypertension development [24]. With respect to the indicators present in men and women, the study found that, for men, stressors associated with work (e.g., low work status, unemployment, threat of unemployment) and for women, stressors associated with a poor psychological state (e.g., depression, loneliness, social isolation), were responsible for the development of hypertension. However, it is widely known that women, in general, present with more complaints concerning health than men, and are characterized by greater frustration, sleep problems, and excess housework, all of which can reduce their HRQoL.

Uncontrolled BP may be one of the most important factors influencing HRQoL. In some studies, an inverse relationship has been noted between higher systolic BP and diastolic BP and the level of HRQoL. This relationship was present across all age groups and applied to isolated systolic hypertension in elderly individuals. It has also been suggested that increased diastolic BP > 95 mmHg is associated with worse wellbeing, and that intensive antihypertensive therapy decreases the frequency and progression of side effects [25]. Results from the Trial of Antihypertensive Interventions and Management (TAIM) also found that reducing BP, irrespective of the treatment option, led to improved quality of sleep, increased sexual activity, and satisfaction with the state of one’s health [26]. However, the results of the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS) [27] suggested that, even with a reduction in BP, differences existed in the influence of specific groups of drugs on HRQoL.

Taking into account current evidence, it is difficult to state if the impact of antihypertensive treatment on HRQoL is dependent solely upon a reduction in BP or is possibly due to the effect of certain drugs. It is worth noting that, though BP was responsible for only 17% of the variability in general HRQoL in one of our studies, it was the strongest clinical factor connected with HRQoL [17].

It is also known that HRQoL changes with the number of drugs used. Based on available data, it seems that the HRQoL of hypertensive subjects is associated (i) with the degree of BP control and (ii) with the number of drugs used. These results confirm conclusions reached in clinical studies undertaken in recent years [13, 28] concerning the necessity for good control of BP (BP < 140/90 mmHg), including its potential influence on improving HRQoL.

Education is one of the most important factors determining HRQoL. Normotensive and hypertensive individuals with higher levels of education, irrespective of sex, are characterized by a higher HRQoL. In contrast, low levels of education and low socioeconomic status are associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to hypertension as well as a reduced HRQoL [13, 27, 29]. These individuals often constitute a subpopulation not very compliant with therapy, who care less about their health and — as shown by epidemiological studies — belong to a group at higher risk of developing cardiovascular complications.

Obesity is another important factor influencing HRQoL, especially in hypertensive women. In women, obesity negatively influences such dimensions of HRQoL as physical health, quality of sleep, sexuality, capacity for everyday functioning, and social interactions.

Side effects of drugs constitute an important problem in the pharmacotherapy of arterial hypertension. It has been argued that they may explain the poor effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy observed in everyday practice. Some of the side effects are non-specific (e.g., headaches), whereas other side effects result from the class of drugs used (e.g., coughing in those treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or facial flushing and peripheral edema in subjects treated with calcium-channel blockers). In a study undertaken in Poland [30] only one-quarter of those treated with antihypertensive drugs directly complained to physicians about side effects, whereas > 70% of them experienced various symptoms (e.g., dry mouth, polyuria, dry cough).

A useful indicator of QoL is the number of drugs taken by the subject. A close relationship exists between the number of drugs taken and HRQoL. It is known that, to reach BP control, > 60% of patients must take 2–3 drugs. Hence, in keeping with guidelines set by the European Society of Hypertension, we recommended combination preparations. These are characterized not only by their effectiveness but also by a reduced frequency of side effects due to their decreased dosage,.

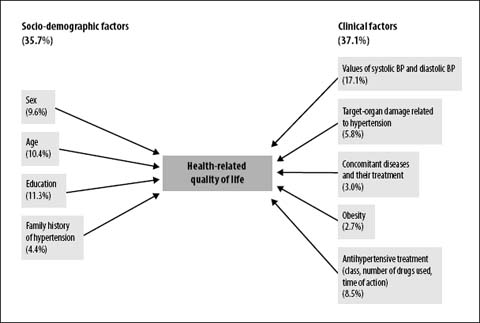

A study carried out in Poland in a population with essential arterial hypertension [15, 17] demonstrated that sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, education, and family burden accounted for ≈36% of the general QoL. In addition, various clinical factors also influence HRQoL (e.g., BP, effectiveness of BP control, disease complications, number of drugs used, body weight). In hypertensive subjects, these clinical factors explained a further 37% of the variability in HRQoL (Fig. 2.3). This observation further supports the view that HRQoL is determined by various factors, and that no factor can be considered to be separate from the others, nor discounted in any way. Furthermore, a common methodological and interpretative mistake which should be avoided is studying only one factor influencing HRQoL.

Fig. 2.3

Socio-demographic and clinical factors influencing health-related Quality of Life in hypertension subjects. Reproduced from [17], with permission

The data shown above suggest that improving the HRQoL of hypertensive individuals is dependent upon many factors. Considering the relationship between elevated BP and degree of cardiovascular risk, the first step is BP control. Analyses of data from a subpopulation of 922 subjects from the Hypertension Optimal Treatment Study found that reducing diastolic pressure to < 80 mmHg was safe and could lead to significant improvement in general wellbeing [28]. This effect was noted during use of a long-acting calcium antagonist.

A study performed in Poland [17] found the highest HRQoL level, both in hypertensive men and women when systolic BP was 125–140 mmHg and diastolic BP was 75–90 mmHg. Prospective studies confirmed that a reduction in systolic BP and diastolic BP slowed down the process of decreasing HRQoL in older age, and positively influenced psychological (e.g., cognitive function, mood) and physical (e.g., physical dexterity, vitality) ability. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial was devoted to the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. The results from this study suggested the possibility for decreasing the frequency of dementia using calcium antagonists [31]. Data from this study also suggested that lowering BP leads to improved sleep quality, a lower prevalence of somatic complaints, increased satisfaction with one’s health, and improved sexual function.

It is equally important to treat other risk factors for CVD. In non-pharmacological management, reducing the weight of the subject seems to exert the greatest effect on HRQoL. Some studies, including the TOMHS, confirm this point: reducing weight improved HRQoL not only during antihypertensive treatment but also with a placebo. It is known that normalizing BP using non-pharmacological methods increases HRQoL more so than by pharmacological treatment alone [27].

Data suggest that regular physical activity, reducing the consumption of alcohol, and stopping smoking may slightly improve HRQoL. Restricting sodium intake has not yet been definitively proven to increase QoL. HRQoL has also been shown to be positively influenced by certain relaxation techniques used to lower BP. However, application of such techniques requires time, skilled personnel, and cooperation from the patient. When beginning lifestyle modification, a slight worsening in HRQoL should be expected initially (especially if incorporating many lifestyle changes simultaneously). Afterwards, HRQoL improves significantly.

QoL and Antihypertensive Treatment

It has been found that significant decreases in HRQoL, even before starting treatment, are associated with an increased risk of death from CVD independent of classical risk factors (including an increased risk of stroke) [32].

The vast majority of clinical studies examining the HRQoL of hypertensive subjects have focused on monotherapy. Simultaneously, new research programs encompassing thousands of subjects showed that combined therapy (i.e., two or three drugs) should be used in > 60% of individuals with hypertension to achieve appropriate control of BP. Theoretically, combined therapy should change HRQoL but in a manner that is dependent upon the specific drugs chosen. Choice of drug is of fundamental importance from the perspective of the HRQoL of the subject. Despite methodological differences between studies, results suggest that significant qualitative and quantitative differences influence the effect of the main antihypertensive drugs upon HRQoL. It has also been suggested that differences exist between the drugs in each group. The time of action of the drug is of significant importance to HRQoL: longer-acting drugs are more positively rated by patients than short-acting drugs. Of equal importance is the dosage: in general, the lower the dose of an antihypertensive drug, the higher the HRQoL of the individual. This is why combining a small and medium dose of two drugs in one tablet is especially advantageous. New-generation drugs are better for HRQoL than older-generation agents. Therefore, careful attention should be paid to the choice of drugs used in clinical practice. Long-acting drugs (especially ones which are used once daily and offer minimal and/or infrequent side effects) should be recommended (Table 2.1). The values of BP that are optimal for HRQoL are 130–140 mmHg for systolic BP and 75–90 mmHg for diastolic BP [15, 28].

Table 2.1

Common side effects of antihypertensive drugs

Drug class | Side effects | Psychomotor function |

|---|---|---|

High blood pressure alone | Headache, epistaxis, blurred vision, palpitations, tiredness | |

Diuretics | ||

Thiazide | Impotence, decreased libido, lethargy, constipation, nausea, dizziness | |

Indapamide | Dizziness, constipation, rarely decreases libido | Improved verbal and intellectual function |

Beta-adrenolytics | Shortness of breath, lethargy, dizziness, vivid dreaming, cold extremities, vision problems, decreased tolerance for physical activity | Prolonged complex-reaction time, impaired verbal memory and psychosensory function, depression |

Calcium antagonists | ||

Dihydropyridines | Headaches and dizziness, hot flushes, erythema, lower-limb edema, nausea | Improved short-term memory, improved psychophysical vitality, delayed development of dementia? |

Non-dihydropyridines | Constipation, headaches and dizziness, nausea | |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Dry cough, rash, trouble with or lack of taste | Opioid-resistant action, improved memory? |

Angiotensin II-receptor blockers | Incidence of side effects similar to placebo – most often headaches and dizziness | Improved memory and learning ability? Delayed development of dementia? |

Alpha-blockers | Orthostatic hypotension, fatigue, lethargy, headaches, nasal sinus edema | |

Centrally acting drugs | ||

Rilmenidine, moxonidine | Minimal lethargy | |

Methyldopa | Diarrhea, fatigue, weakness, dry mouth, vivid dreams | Worsened verbal memory |

Clonidine | Fatigue, sleep disturbance, dry mouth, constipation, lethargy, sedation | Prolonged complex-reaction time Depression – especially with reserpine |

2.5 Lifestyle Modification

Large studies examining the influence on HRQoL of non-pharmacological management of arterial hypertension are lacking. Single studies carried out many years ago have confirmed that subjects who have been able to reduce their BP without drugs have a better HRQoL than individuals being treated by pharmacological means. In particular, reducing body weight influences improvement in HRQoL [28]. However, restricting the amount of sodium in the diet may exacerbate erectile dysfunction and lead to fatigue and disturbed sleep.

Instituting changes in the lifestyle of subjects interferes with their already accepted behaviors, which not necessarily influences their HRQoL in a positive way. These recommendations exert a psychological effect on some individuals who consider themselves to be “restricted” and “pressured” into reorganizing their lives to accommodate new dietary requirements or to incorporate regular physical activity. Such individuals experience a temporary decline in their wellbeing, for example, due to physiologic effects after ceasing smoking or restricting alcohol consumption. They may also lose some of their social privileges due to the effect of changing their current lifestyle. This period of worsening HRQoL experienced after lifestyle modification may last from 3 months to 6 months. This is a critical period in which the subject often gives up instituting lifestyle changes. This is why he/she should be under supervision during this time and supported in his/her efforts to maintain the necessary changes in lifestyle.

2.6 Drugs Used to Treat Hypertension

Diuretics

The ways in which diuretics influence HRQoL has not been documented fully. Studies have confirmed that individuals being treated with diuretics more often complain about sexual dysfunction, depressed mood, and/or cognitive dysfunction (Table 1). The negative influence of thiazide diuretics on sexual function has been confirmed in multicenter studies such the Medical Research Council (MRC) study and TAIM study [26], in which 11–25% (chlortalidone) and 18% (bendroflumethiazide, hydrochlorothiazide) of treated male subjects noted an increased prevalence of impotence. Conversely, only 1.6% more males using spironolactone noted an increased prevalence of impotence compared with the placebo group. In the TOMHS [33], after 24 months, the prevalence of impotence in the group treated with chlorthalidone was 17% and was 8% in the placebo group (p < 0.03). However, after 48 months of observation, no difference in the prevalence of impotence was noted between the two groups.

Paran et al. [34] noted a significant improvement in certain dimensions of the HRQoL of hypertensive subjects 6–9 months after withdrawing thiazide diuretics. However, after withdrawing diuretics, participants did not reach the same level of HRQoL as patients who were never previously treated with diuretics. Compared with thiazide diuretics, the non-thiazide diuretic indapamide was found to be tolerated just as well by younger patients as those aged > 65 years and caused: fewer side effects; fewer sleep disturbances; a decreased prevalence of impotence [35].

Diuretics such as chlorthalidone and especially hydrochlorothiazide used in large doses exert a decisively negative influence on HRQoL. Lower doses of these drugs as well as spironolactone have a better influence on HRQoL. For HRQoL, in keeping with current recommendations, diuretics should be used in small doses, and often do not yield any side effects.

Beta-adrenergic Receptor Blockers

The influence of beta-blockers on HRQoL is focused on the typical side effects and symptoms these drugs may evoke in the central nervous system (CNS) (Table 1). These symptoms arise from the lipophilic property of certain beta-blockers, which allows them to readily penetrate the blood—brain barrier. CNS-related side effects elicited by beta-blockers most often include: disturbed phases of sleep; insomnia; colorful and vivid dreams; nightmares; memory problems; hallucinations; a feeling of psychophysical fatigue; and emotional instability. In some subjects, low moods and depression may be present several months after beginning treatment with beta-blockers. However, the minimally anxiolytic action of beta-blockers must be noted, and is especially pronounced in the elderly.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree