Uh-oh! Forgot to measure the QT interval!

DESCRIPTION

The QT interval is the distance from the start of the QRS to the end of the T wave, and is best measured with calipers or a very accurate paper clip. Computers seem to have problems with QT intervals, and so until we are completely replaced by them, it’s best to measure the QT intervals yourself. The interval normally gets shorter as the heart rate speeds up, and as you might guess, it gets longer as the heart rate slows down. At a heart rate of 60 the normal QT is 0.4 seconds (two big boxes) in duration. There are complicated formulas for correcting the QT for faster or slower heart rates (the QT corrected for heart rate is called the QTc, now you know something almost nobody else knows!), but absent a slide rule or calculator that can figure out square roots (or a useful website that can calculate the QTc: http://www.medical-calculator.nl/calculator/QTc/, last accessed 8/7/2012), all you need to know is a QT of 0.5 seconds should make you start to worry, and a QT of 0.6 seconds (three big boxes) should make a cold sweat break out and start rolling down your neck.

Sinus rhythm with a prolonged QT interval can otherwise look totally normal, although at times the T wave can have all sorts of funny terminal wiggles and bumps (“U” waves).

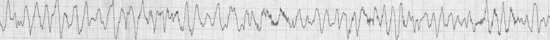

Why worry about a prolonged interval in an arrhythmia text? Because a prolonged QT interval is a set-up for a potentially fatal arrhythmia called torsades de pointes (don’t worry, no one knows how to pronounce it). Torsades (those of us who are good friends of the arrhythmia can use its first name) is a rapid, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) (page 33), which truly looks a lot like ventricular fibrillation except it’s a bit more organized. Unlike monomorphic VT, here the QRS is constantly twisting around the baseline and each beat looks different. The arrhythmia may be self-limiting, stopping by itself after a brief spurt, but at other times it may not stop, degenerating into its close relative ventricular fibrillation.

HABITAT

We can find this arrhythmia wherever a patient is on a monitor, and not necessarily in a CCU. In fact, since this arrhythmia may be triggered by commonly prescribed drugs, such as certain antibiotics, you may encounter it outside of the hospital as well. Since most people outside of the hospital are not walking around with monitors, however, the only way you might recognize it on an outpatient is when they keel over and paramedics apply one.

CALL

“Aieee!! Get the paddles!!” or “Charging … clear …<zap!!>”

RESEMBLANCE TO OTHER ARRHYTHMIAS

From its appearance and the similarity of this call to the call of sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, you should realize torsades is actually closely related to both, and like some warblers, is sometimes best left for experts to distinguish. A key feature is that if you want to call an arrhythmia torsades then you have to be able to demonstrate a prolonged QT before or after the arrhythmia, and should be able to show the patient has been receiving a drug or has an electrolyte abnormality which is known to prolong the QT interval. One useful source for a list of QT prolonging drugs may be found at http://www.qtdrugs.org (last accessed 6/19/2012).

CARE AND FEEDING

Along the lines of avoiding being eaten by polar bears by simply not climbing into the polar bear exhibit (100% effective unless you are camping in the Arctic), torsades can almost always be prevented! By carefully watching the QT interval, keeping the potassium normal (preferably in the mid-4 range), keeping the magnesium normal, and most importantly, by avoiding drugs or combinations of drugs which can prolong the QT (or by watching the QT interval closely if you must use those drugs), this beast can be avoided.

If you see a prolonged QT alert the appropriate staff, review the medications, and try to stop the offending agent. We have seen QT prolongation and torsades with azithromycin, levofloxacin, methadone, citalopram, fluconazole, and most antiarrhythmics. Correct the electrolytes, especially potassium and magnesium. If you actually see runs of torsades, besides stopping any offending agents and moving the patient to the CCU, correct the electrolytes emergently, consider intravenous magnesium sulfate, and consider strategies to accelerate the heart rate (while also taking steps to slow your own heart rate). A faster heart rate will shorten the QT and often stabilize the rhythm while the bad drugs are “washing out.” (Pledges to attend religious services, to eat Kosher, or to donate large sums of money to charities if the patient stabilizes may also be helpful.)

If torsades won’t stop, then shock the patient while doing all the other stuff. This is definitely a situation to call for backup, especially the electrophysiologist. Don’t argue with the Infectious Disease consultant, just stop the azithromycin and levofloxacin. They can always come up with another weird combination that will kill the bugs without blocking those crazy potassium channels. And definitely don’t argue about whether a rapid polymorphic VT is ventricular fibrillation or not … if there is a sustained hemodynamically unstable rhythm just shock it asynchronously and argue about it later.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree