Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic, recurrent, contagious infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It is estimated that in 2006 active pulmonary TB will develop in >10 million individuals and will lead to >2 million deaths (1,2,3). Most cases occur in southeast Asia and Africa. Of the estimated 8.8 million new cases in 2003, 3 million occurred in southeast Asia, 2.4 million in Africa, 439,000 in Europe and 370,000 in the Americas (4). The incidence in the Americas is lowest in Canada and in the United States. During 2004, a total of 14,511 confirmed TB cases (4.9 cases per 100,000 population) were reported in the United States (5). Slightly >half (54%) of the US cases were foreign-born persons (5).

Patients with active pulmonary TB may be asymptomatic, have mild or progressive dry cough, or present with multiple symptoms including fever, fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, and cough producing bloody sputum. It is estimated that each patient with active disease will infect on average between 10 and 15 people every year (4). Many of the cases of active TB are not recognized. It is likely that the World Health Organization 2005 target to detect at least 70% of all estimated sputum smear-positive cases worldwide and to treat at least 85% of them successfully was not met (6).

Development of Infection

M. tuberculosis is an aerobic, nonmotile, non–spore-forming rod that is highly resistant to drying, acid, and alcohol. It is transmitted from person to person through droplet nuclei containing the organism and is spread mainly by coughing. The contagiousness of a patient with TB increases with the greater extent of the disease, the presence of cavitation, the frequency of coughing, and the virulence of the organism (7). The risk of developing active TB is greatest in patients with altered host cellular immunity. These include extremes of age, malnutrition, cancer, immunosuppressive therapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, end stage renal disease, and diabetes.

Pathogenesis

Inhaled mycobacteria are phagocytized by alveolar macrophages, where the organisms multiply and eventually kill the cells. Interaction of macrophages with T lymphocytes results in differentiation of macrophages into epithelioid histiocytes (7). The epithelioid histiocytes aggregate into small clusters resulting in granulomas. After several weeks, granulomas are well formed, and their central portions undergo necrosis (7). As the disease progresses, individual necrotic foci tend to enlarge and coalesce. The rapid

bacillary growth phase is arrested with the development of cell-mediated immunity and delayed-type hypersensitivity at 2 to 10 weeks after the initial infection (8,9). The initial focus of parenchymal disease is termed the Ghon focus. The Ghon focus may be microscopic or large enough to be visible radiologically. It either enlarges as the disease progresses or, much more commonly, undergoes healing. Healing may result in a visible scar that may be dense and contain foci of calcification. However, usually there is residual central necrotic material. Although the disease at this stage is inactive, the encapsulated necrotic areas contain viable organisms and are a potential focus for reactivation in later life (7).

bacillary growth phase is arrested with the development of cell-mediated immunity and delayed-type hypersensitivity at 2 to 10 weeks after the initial infection (8,9). The initial focus of parenchymal disease is termed the Ghon focus. The Ghon focus may be microscopic or large enough to be visible radiologically. It either enlarges as the disease progresses or, much more commonly, undergoes healing. Healing may result in a visible scar that may be dense and contain foci of calcification. However, usually there is residual central necrotic material. Although the disease at this stage is inactive, the encapsulated necrotic areas contain viable organisms and are a potential focus for reactivation in later life (7).

During the early stage of infection, organisms commonly spread through lymphatic channels to regional hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes and through the bloodstream to more distant sites in the body. The combination of the Ghon focus and affected lymph nodes is known as the Ranke complex (7). The course of the disease in lymph nodes is similar to that in the parenchyma, consisting initially of granulomatous inflammation and necrosis followed by fibrosis and calcification. However, the inflammatory reaction is usually much greater in lymph nodes resulting in radiologically visible lymphadenopathy. Hematogenous dissemination in primary TB is probably common but seldom results in miliary disease (7).

The initial infection is usually clinically silent. Development of specific immunity is usually adequate to limit further multiplication of the bacilli (10). Some of the bacilli remain dormant and viable for many years. This condition, known as latent TB infection, may be detectable only by means of a positive purified protein derivative tuberculin skin test or by the presence of radiologically identifiable calcification at the site of the primary lung infection or in regional lymph nodes (11). In approximately 5% of infected individuals immunity is inadequate and clinically active disease develops within 1 year of infection, a condition known as progressive primary TB (8). Risk factors for progressive primary disease include immunosuppression (especially HIV infection), extremes of age, or a large inoculation of mycobacteria. For most infected individuals, however, TB remains clinically and microbiologically latent for many years.

In approximately 5% of the infected population, endogenous reactivation of latent infection develops many years after the initial infection (8). Such reactivation is frequently associated with malnutrition, debilitation, or immunosuppression (12). Postprimary TB tends to involve predominantly the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes. This localization is likely due to a combination of relatively higher oxygen tension and impaired lymphatic drainage in these regions (7,11). As distinct from primary TB, in which healing is the rule, postprimary TB tends to progress. The main abnormalities are progressive extension of inflammation and necrosis, frequently with the development of communication with the airways and cavity formation (7). Endobronchial spread of necrotic material from a cavity may result in tuberculous infection in the same lobe or in other lobes. Hematogenous dissemination may result in miliary TB. Although most cases of postprimary TB probably result from reactivation of organisms in a focus acquired during the primary infection in some cases, postprimary TB may result from reinfection by new organisms.

Radiologic Manifestations

Patients who develop the disease after initial exposure are considered to have primary TB. Patients who develop the disease as a result of reactivation of a previous focus of TB or because of reinfection are considered to have postprimary (reactivation) TB. Traditionally, it was believed that the clinical, pathologic, and radiologic manifestations of postprimary TB were quite distinct from those of primary TB. However, more recent studies based on DNA fingerprinting suggest that the radiographic features are often similar in patients who apparently have primary disease and those who have postprimary TB (13). Time from acquisition of infection to development of clinical disease does not reliably predict the radiographic appearance of TB. The only independent predictor of radiographic appearance is the integrity of the host immune response (13). Patients with normal response tend to show parenchymal granulomatous inflammation with slowly progressive nodularity and cavitation whereas patients with immunodeficiency have a tendency to develop lymphadenopathy. Because these results are preliminary and because the vast majority of published data are based on the traditional concept of primary and postprimary disease, we follow the traditional outline in this book.

Primary Tuberculosis

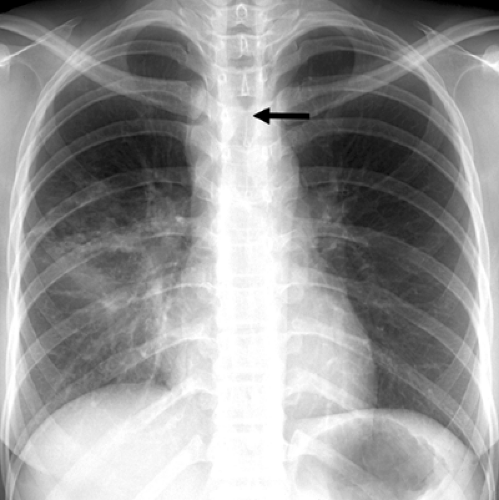

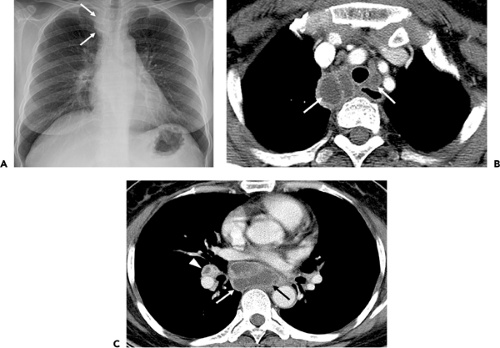

The initial parenchymal focus of TB (Ghon focus) may enlarge and result in an area of airspace consolidation (see Fig. 3.1) or, more commonly, undergo healing by transformation of the granulomatous tissue into mature fibrous tissue. Such healing is often accompanied by dystrophic calcification of the necrotic tissue. Spread of organisms to the regional lymph nodes results in granulomatous inflammatory reaction and lymph node enlargement (see Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). The combination of the Ghon focus and affected nodes is known as the Ranke complex.

Primary TB occurs most commonly in children, but is being seen with increasing frequency in adults (see Figs. 3.1,3.2,3.3) (12,14). There is considerable difference in the prevalence of radiologic findings in children compared to that in adults (see Table 3.1). The most common abnormality in children consists of lymph node enlargement, which is seen in 90% to 95% of cases (15,16). The lymphadenopathy is usually unilateral and located in the hilum or paratracheal region. On CT scan, the enlarged

nodes frequently have focal areas of low attenuation and show peripheral (rim) enhancement (Fig. 3.2) (17,18). The former corresponds to the central necrotic portion of the node and the latter to the surrounding vascular rim of granulomatous inflammatory tissue. The enlarged nodes can compress the adjacent bronchi and result in atelectasis, which is usually lobar and right-sided.

nodes frequently have focal areas of low attenuation and show peripheral (rim) enhancement (Fig. 3.2) (17,18). The former corresponds to the central necrotic portion of the node and the latter to the surrounding vascular rim of granulomatous inflammatory tissue. The enlarged nodes can compress the adjacent bronchi and result in atelectasis, which is usually lobar and right-sided.

Airspace consolidation, related to parenchymal granulomatous inflammation and usually unilateral, is evident radiographically in approximately 70% of children with primary TB (15). It shows no predilection for any particular lung zone (15). As compared to children, adults who have primary TB are less likely to have lymph node enlargement (10% to 30% of patients) and more likely to have parenchymal consolidation (approximately 90% of patients) (Fig. 3.3) (19,20). The parenchymal consolidation in primary TB is most commonly homogeneous but may also be patchy, linear, nodular, or mass-like (21). Parenchymal consolidation in adults may involve predominantly or exclusively the upper or lower lung zones (21). Pleural effusion is seen in 5% to 10% of children and 30% to 40% of adults with primary TB (15,17,20).

The pleural effusion is usually unilateral and on the same side as the primary focus of TB. The effusion may be large and present in patients without evidence of parenchymal disease on chest radiographs (20).

The pleural effusion is usually unilateral and on the same side as the primary focus of TB. The effusion may be large and present in patients without evidence of parenchymal disease on chest radiographs (20).

Postprimary Tuberculosis

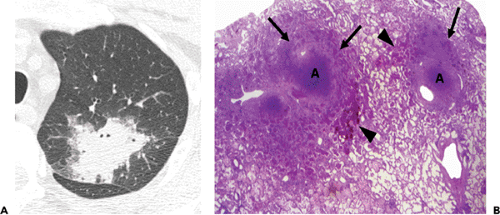

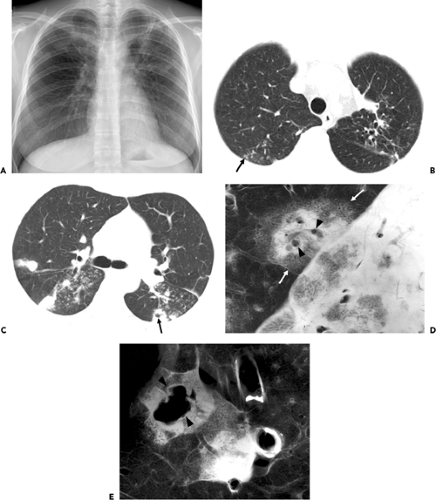

Postprimary TB typically involves mainly the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and/or the superior segments of the lower lobes (see Figs. 3.4 and 3.5) (7,21,22). As with primary disease, the postprimary form is characterized histologically by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Coalescence and enlargement of multiple foci of inflammation result in progressive consolidation. Destruction of lung parenchyma and scarring result in a nodular appearance (Fig. 3.4). Extension into an airway is followed by the drainage of necrotic material and the formation of one or more cavities (Fig. 3.5). Endobronchial spread results in the formation of additional foci of tuberculous disease in other regions of the lungs (see Figs. 3.4,3.5,3.6).

TABLE 3.1 Primary Tuberculosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

The most common radiographic manifestation of postprimary TB consists of focal or patchy heterogenous consolidation involving the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes (see Table 3.2) (Figs. 3.4,3.5,3.6) (21,22). Another common finding is the presence of poorly defined nodules and linear opacities (fibronodular pattern of TB).

In one review of the radiographic features of 158 patients with postprimary TB, approximately 55% presented with consolidation, 25% with a fibronodular pattern, and 5% with a mixed pattern (22). Single or multiple cavities are evident radiographically in 20% to 45% of patients (20,21,22). Air–fluid levels are seen in 10% to 20% of tuberculous cavities (20,22). In approximately 85% of patients the cavities involve the apical and/or posterior segment of the upper lobes and in approximately 10% the superior segments of the lower lobes (21). Endobronchial spread, manifested as 4 to 10 mm diameter nodules distant from the site of the cavity, is evident radiographically in 10% to 20% of cases (22,23).

In one review of the radiographic features of 158 patients with postprimary TB, approximately 55% presented with consolidation, 25% with a fibronodular pattern, and 5% with a mixed pattern (22). Single or multiple cavities are evident radiographically in 20% to 45% of patients (20,21,22). Air–fluid levels are seen in 10% to 20% of tuberculous cavities (20,22). In approximately 85% of patients the cavities involve the apical and/or posterior segment of the upper lobes and in approximately 10% the superior segments of the lower lobes (21). Endobronchial spread, manifested as 4 to 10 mm diameter nodules distant from the site of the cavity, is evident radiographically in 10% to 20% of cases (22,23).

TABLE 3.2 Postprimary Tuberculosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 3.4 Postprimary tuberculosis in a 33-year-old woman. A: Chest radiograph shows multiple variable-sized nodules with poorly defined margins in both upper lung zones. B: Computed tomography (CT) image (2.5-mm collimation) obtained at the level of the great vessels shows tree-in-bud opacities (arrow) in the right upper lobe. Also note bronchiectasis and reticulation in the left upper lobe due to previous tuberculous infection. C: CT image obtained at the level of the main bronchi shows cavitating nodule (arrow) in the left lower lobe, bilateral noncavitating nodules and tree-in-bud opacities. D: Contact radiograph and surface photograph of sliced lung specimen obtained from a different patient who died of endobronchial spread of tuberculosis show lobular consolidation (arrows) and 2- to 3-mm diameter centrilobular cavities (arrowheads). Lobular consolidation consists of loose periphery and compact center. Microscopic examination (not shown) revealed caseation necrosis at the dense center and nonspecific inflammation at loose periphery. E: Contact radiograph of lung specimen obtained from an area adjacent to that in (D) demonstrates consolidation in a secondary pulmonary lobule containing larger necrotic cavity (arrowheads). Cavitation may begin at the lobular center, followed by coalescence of small cavities, resulting in a larger cavity. (Courtesy of Dr. Im J.-G. Seoul, Korea: Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Hospital.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|