27.2 ETIOLOGIES

The 2008 Dana Point Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension (Table 27.1) reflects the wide variety of specific disease processes that ultimately lead to PH. The modern groups are based upon similar pathophysiological, clinical and therapeutic characteristics. Scanning the classification list after diagnosing PH may allow for the identification of one or more causes of the elevated right-sided pressure. PH specialists use the classification system when considering treatment options, as the majority of clinical trials involving PH medications have focused on Group 1 diagnoses.

27.3 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Though many distinct disease processes may ultimately cause PH, progressive right-sided heart failure is both the final common pathway and the primary cause of death in patients with this condition. For many of the conditions listed above, the mechanism by which a disease process results in an elevated PA pressure may be apparent. For example, occlusion of the pulmonary vasculature due to chronic thromboembolic disease results in elevated right-sided pressures, as blood is impeded from flowing freely towards the left atrium. Likewise, any etiology resulting in elevated left-sided pressure such as systolic or diastolic dysfunction and valvular disorders can lead to elevated right-sided pressures.

The pathogenesis is less clear for those with PAH. Researchers believe affected individuals may have a genetic predisposition towards developing elevated pulmonary pressures. A subsequent “second hit” in the form of an additional genetic factor, a coexisting disease, or an environmental exposure may be necessary before a patient goes on to develop PAH. Once triggered, the vasoconstrictive, pro-thrombotic phenotype of PAH is likely perpetuated by a complex process involving endothelial cell dysfunction, smooth muscle cell proliferation, inflammation, an underproduction of prostacyclin and nitric oxide with an overabundance of thromboxane A2 and endothelin-1. These pathophysiological alterations in homeostasis form the basis of pulmonary vasoconstriction and subsequent elevated pressures. Accordingly, many of our therapies are guided towards reversing these alterations with hopes of reducing the vasoconstriction.

Table 27.1 Dana Point Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension (2008).

1. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) 1.1 Idiopathic PAH 1.2 Heritable 1.2.1 BMPR2 1.2.2 ALK1, endoglin (with or without herediatary hemorrhagic telangiectasia) 1.2.3 Unknown 1.3 Drug- and toxin-induced 1.4 Associated with 1.4.1 Connective tissue diseases 1.4.2 HIV infection 1.4.3 Portal hypertension 1.4.4 Congenital heart disease 1.4.5 Schistosomiasis 1.4.6 Chronic hemolytic anemia 1.5 Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn 1’. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) 2. Pulmonary hypertension owing to left heart disease 2.1 Systolic dysfunction 2.2 Diastolic dysfunction 2.3 Valvular disease 3. Pulmonary hypertension owing to lung diseases and/or hypoxia 3.1 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3.2 Interstitial lung disease 3.3 Other pulmonary diseases with mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern 3.4 Sleep-disordered breathing 3.5 Alveolar hypoventilation disorders 3.6 Chronic exposure to high altitude 3.7 Developmental disorders 4. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) 5. Pulmonary hypertension with unclear multifactorial mechanisms 5.1 Hematologic disorders: myeloproliferative disorders, splenectomy 5.2 Systemic disorders: sarcoidosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, neurofibromatosis, vasculitis 5.3 Metabolic disorders: glycogen storage disease, Gaucher disease, thyroid disorders 5.4 Others: tumoral obstruction, fibrosing mediastinitis, chronic renal failure on dialysis |

“Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension (Dana Point, 2008)” in: Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. JACC 2009;54(1), Suppl S:S43–54.

27.4 EPIDEMIOLOGY

Given that PH is associated with such a wide variety of underlying diseases, it is helpful to consider the epidemiology of some of the major groups listed in the Dana Point classification scheme. It is important to keep in mind that the majority of patients with PH have elevated right-sided pressures secondary to left heart disease. Table 27.2 shows the prevalence of the major etiologies of PH in a series of 483 patients with pulmonary artery systolic pressures greater than 40 mmHg as measured by transthoracic echocardiogram. “Non-PAH PH,” or Groups 2 through 5, are often due to other disease processes resulting in secondary PH. It is estimated that as many as 1% of patients with advanced COPD have severe PH, giving a prevalence of 3–17 per million. However 100–150 per million patients with COPD may have lesser degrees of PH. The finding of PH in the COPD population is important, as mean pulmonary arterial pressure has been shown to be a strong predictor of mortality. Approximately 33% of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have been shown to have echocardiographically-defined PH which is also a predictor of mortality in this group. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is an important consideration in any evaluation of PH, as approximately 2,500 new cases are diagnosed each year in the US, many of which occur without any acute symptoms. Sleep-disordered breathing is another common cause of PH, and studies have shown that as many as 70% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have some degree of PH.

PAH (Group 1 of the Dana Classification), and specifically idiopathic PAH, is less common with prevalence estimates of 15 cases per million and 5.9 cases per million, respectively. The incidence rates for IPAH are estimated to be on the order of 2.4 cases per million, and together with familial and appetite-suppressant-related cases, make up over 50% of PAH cases. Women are twice as likely as men to develop IPAH. The mean age on onset of IPAH is 37 years, though it may occur through the sixth decade. The second most common form of PAH (30% of PAH cases) occurs in patients with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases or mixed connective tissue disease. Studies indicate that between 7% and 12% of patients with limited cutaneous scleroderma develop PAH; this is an especially vulnerable population, as prognosis is poor. PAH associated with congenital heart disease, portopulmonary hypertension, and HIV round out the most common etiologies of this uncommon disease. In endemic regions of the world, schistosomiasis-associated PAH is a significant health problem with an 8% prevalence in Brazilian patients suffering from hepatosplenic schistosomiasis. Given that close to 200 million people worldwide are infected with schistosomiasis, more than 270,000 people could have this form of associated PAH.

Table 27.2 Prevalence of PH Groups.

| Etiology | Prevalence |

| Left heart disease (Group 2) | 78.7% |

| Lung disease and hypoxemia (Group 3) | 9.7% |

| PAH (Group 1) | 4.2% |

| CTEPH (Group 4) | 0.6% |

| Unclear diagnosis | 6.8% |

27.5 CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Dyspnea is the most common symptom of PH and forms the basis of the World Health Organization classification system (Table 27.3). At the time of diagnosis, patients with PH typically have experienced progressive dyspnea-on-exertion (DOE) over the course of months to years. Fatigue, light headedness, chest pain, palpitations, orthopnea, edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and cough are other common presenting symptoms. Syncope in a patient with PH is indicative of WHO class IV functional status due to RV failure while PH should always be on the differential diagnosis list of anyone admitted with unexplained syncope.

Exam findings suspicious for the presence of PH include a prominent P2, a parasternal lift, a right ventricular S4, a systolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation, an early systolic click, and a diastolic murmur of pulmonary regurgitation. Clues to the etiology of PH include central cyanosis, which may be the result of an intracardiac shunt or Eisenmengers syndrome; clubbing of the fingers due to congenital heart disease; sclerodactyly or Raynaud’s phenomenon as a result of connective tissue disease; splenomegaly, scleral icterus, and caput medusae from portal hypertension; a left ventricular S3, or mitral and/or aortic valve murmurs as a result of left heart disease; and wheezing or protracted expiration secondary to hypoxic lung disease. Findings in advanced PH with right heart failure may include jugular venous distention, a right ventricular S3, edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly.

Table 27.3 World Health Organization Classification of Functional Status.

| Class | Description |

| I | No limitation of usual physical activity |

| II | Mild limitation of physical activity; no discomfort at rest; normal activity causes increased dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain or presyncope |

| III | Marked limitation of physical activity; no discomfort at rest; less than normal activity causes increased dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain or presyncope |

| IV | Discomfort at rest; may have signs of RV failure, symptoms increased by almost any physical activity |

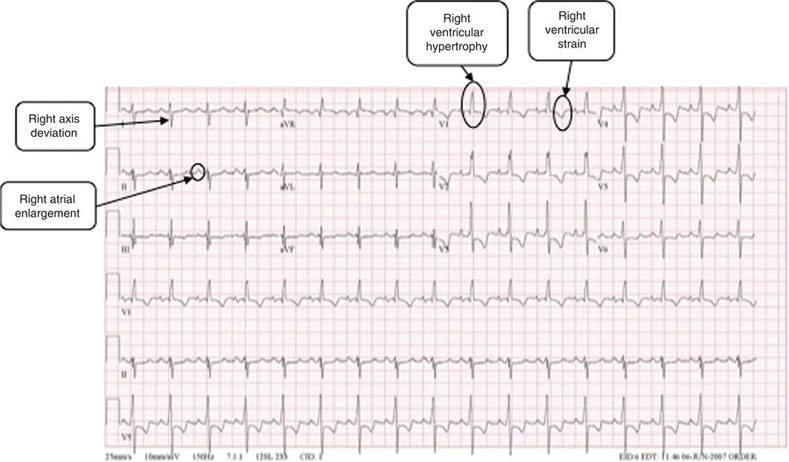

Figure 27.1 This ECG from a patient with pulmonary hypertension shows right axis deviation, right ventricular hypertrophy, and a right ventricular strain pattern. (Source: http://www.cvphysiology.com/Arrhythmias/SAN%20action%20potl.gif, with permission from Dr Richard Klabunde).

27.6 EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree