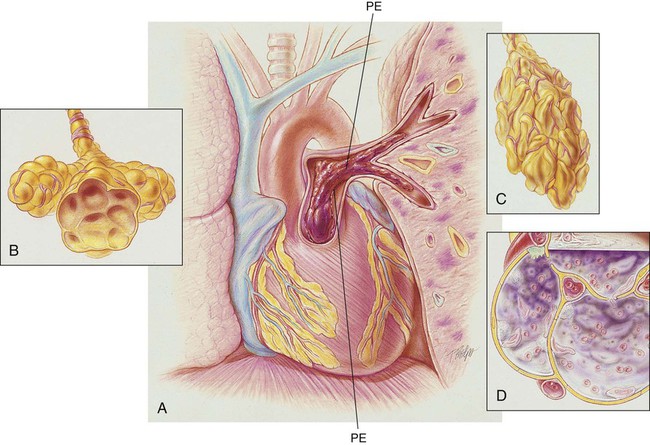

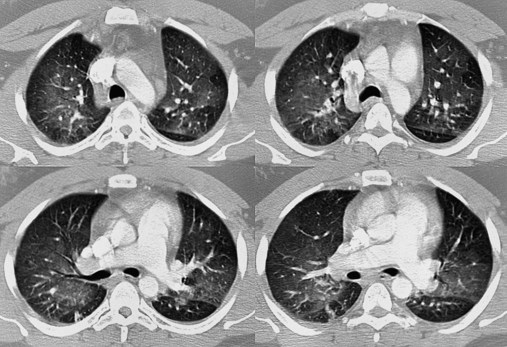

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with pulmonary embolism. • Describe the causes of pulmonary embolism. • List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with pulmonary embolism. • Describe the general management of pulmonary embolism. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. An embolus may originate from one large thrombus or occur as a shower of small thrombi and may or may not interfere with the right side of the heart’s ability to perfuse the lungs adequately. When a large embolus detaches from a thrombus and passes through the right side of the heart, it may lodge in the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery, where it forms what is known as a saddle embolus (partially shown in Figure 20-1). This is often fatal. Although there are many possible sources of pulmonary emboli (e.g., fat, air, amniotic fluid, bone marrow, tumor fragments), blood clots are by far the most common. Most pulmonary blood clots originate—or break away from—sites of deep venous thrombosus (DVT) in the lower part of the body (i.e., the leg and pelvic veins and the inferior vena cava). When a thrombus or a piece of a thrombus breaks loose in a deep vein, the blood clot (now called an embolus) is carried through the venous system to the right atrium and ventricle of the heart and ultimately lodges in the pulmonary arteries or arterioles. There are three primary factors, known as Virchow’s triad, associated with the formation of DVT. Virchow’s triad includes (1) venous stasis (i.e., slowing or stagnation of blood flow through the veins), (2) hypercoagulability (i.e., the increased tendency of blood to form clots), and (3) injury to the endothelial cells that line the vessels. Box 20-1 provides common risk factors for pulmonary embolism. Depending on how much of the lung is involved, the size of the embolism, and the overall health of the patient, the signs and symptoms of a pulmonary embolism can vary greatly. Box 20-2 provides common signs and symptoms that often justify additional—and sometimes urgently needed—diagnostic procedures used to diagnose a suspected pulmonary embolism. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can dramatically reduce the mortality and morbidity of the disease. The spiral or helical computed tomography (CT) scan (pulmonary embolism CT scan) is fast becoming the first-line test for diagnosing suspected pulmonary embolism (Figure 20-2). Because the spiral CT scanner rotates continuously around the body, it can provide a three-dimensional image of any abnormalities with a higher degree of accuracy. A dye (contrast medium) is usually used to help visualize the structures of the lungs. It only takes about 20 seconds as opposed to 20 minutes for the standard CT scan. Because the spiral CT scan is fast, it is easier to capture the dye while it is still in the pulmonary arteries. The spiral CT scan exposes the patient to more radiation than the standard x-ray examination but increases the risk of an allergic reaction to the contrast medium (rare). The spiral CT scan is considered to be more sensitive than the ventilation-perfusion scan (

Pulmonary Embolism

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Etiology and Epidemiology

Diagnosis and Screening

Spiral (Helical) Computed Tomography Scan

scan) and pulmonary angiogram, discussed later.

scan) and pulmonary angiogram, discussed later.

Scan)

Scan)

scan is reliable only at the extremes of interpretation (i.e., the test confirms that the lungs are normal or that there is a high probability of a pulmonary embolism). The

scan is reliable only at the extremes of interpretation (i.e., the test confirms that the lungs are normal or that there is a high probability of a pulmonary embolism). The  scan often raises more questions than it answers. This test is slowly being replaced by more sensitive and rapid tests, such as spiral CT scans.

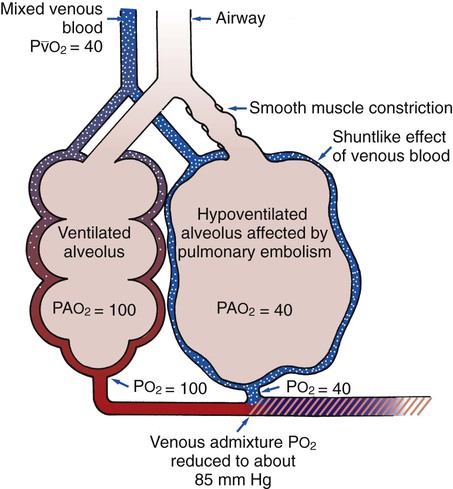

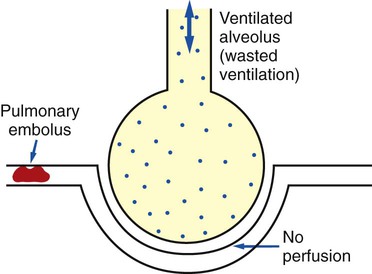

scan often raises more questions than it answers. This test is slowly being replaced by more sensitive and rapid tests, such as spiral CT scans. ) ratio distal to the pulmonary embolus is high and may even be infinite if there is no perfusion at all (

) ratio distal to the pulmonary embolus is high and may even be infinite if there is no perfusion at all (

ratio at the onset of a pulmonary embolism, this condition is quickly reversed, and a decrease in the

ratio at the onset of a pulmonary embolism, this condition is quickly reversed, and a decrease in the  ratio occurs. The pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the decreased

ratio occurs. The pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the decreased  ratio are as follows: In response to the pulmonary embolus, pulmonary infarction develops and causes alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, and parenchymal necrosis. In addition, the embolus is believed to activate the release of humoral agents such as serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandins into the pulmonary circulation, causing bronchial constriction. Collectively, the alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, tissue necrosis, and bronchial constriction lead to decreased alveolar ventilation relative to the alveolar perfusion (decreased

ratio are as follows: In response to the pulmonary embolus, pulmonary infarction develops and causes alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, and parenchymal necrosis. In addition, the embolus is believed to activate the release of humoral agents such as serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandins into the pulmonary circulation, causing bronchial constriction. Collectively, the alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, tissue necrosis, and bronchial constriction lead to decreased alveolar ventilation relative to the alveolar perfusion (decreased  ratio). As a result of the decreased

ratio). As a result of the decreased  ratio, pulmonary shunting and venous admixture ensue.

ratio, pulmonary shunting and venous admixture ensue. ratio that develops from the pulmonary infarction (atelectasis and consolidation) and bronchial constriction (release of cellular mediators) that actually causes the reduction of the patient’s arterial oxygen level. As this condition intensifies, the patient’s oxygen level may decline to a point low enough to stimulate the peripheral chemoreceptors, which in turn initiates an increased ventilatory rate.

ratio that develops from the pulmonary infarction (atelectasis and consolidation) and bronchial constriction (release of cellular mediators) that actually causes the reduction of the patient’s arterial oxygen level. As this condition intensifies, the patient’s oxygen level may decline to a point low enough to stimulate the peripheral chemoreceptors, which in turn initiates an increased ventilatory rate.