Fig. 12.1

Survival curves according to the seventh IASLC staging system. In panel A, the survival figures for the different clinical stages are presented. In panel B, the same survival curves are presented but now for the pathological staging. There is a clear difference between the number of stages IB and IIA between the clinical and pathological stages, indicating that imaging techniques in these two groups are often difficult (From The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Seventh) Edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. Peter Goldstraw, FRCS,* John Crowley, Ph.D.,† Kari Chansky, MS,† Dorothy J. Giroux, M.Sc.,†Patti A. Groome, Ph.D.,‡ Ramon Rami-Porta, M.D.,§ Pieter E. Postmus, Ph.D., Valerie Rusch, M.D., and Leslie Sobin, M.D.,# on behalf of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee and Participating Institutions. Reprinted with permission from Wolters Kluwer)

Clinical Staging

Clinical staging is the process of determining the extent of the disease by using limited invasive procedures and anatomical landmarks, excluding aspects of the biological behavior of the disease or patient characteristics. It comprises of a tumor or T status, a lymph node or N status, and the presence of metastases or M status. After finalizing the required examinations, the clinical staging will be noted as a cTxNxMx. It must be noted that clinical staging is not as accurate as the final pathological staging, which is indicated as a pTxNxMx. In addition, an interim staging after induction chemo- and radiotherapy will be indicated by yTxNxMx.

Clinical staging consists of the following procedures: physical examination, radiological examination, nuclear medicine examination, endoscopic investigations, and limited surgical interventions.

Physical Examination

The first step in staging is to examine the patient and find signs or symptoms that indicate local or distant dissemination of the disease. Findings during the physical examination will also be of help to plan the next steps. This will avoid examinations that will not contribute to the staging process and finally shorten the time between presentation and start of treatment. Signs of collateral blood flow and elevated central venous pressure will urge the physician to order vascular contrast examinations, sometimes combined with placement of an expandable vascular stent. The appearance of enlarged lymph nodes in the supraclavicular region will indicate at least an N3 status. Signs of Horners’ syndrome (unilateral ptosis, myosis, enophthalmus, and reduced sweating) or pain in one shoulder or arm indicates involvement of the cervical plexus by invasion of the tumor. A low position of the diaphragm or reversed movement during respiration is indicative of severe COPD or involvement of the phrenic nerve. Diminished breath sounds and dullness at percussion are indicators of pleural effusion, atelectases, or consolidation of a part of the lung. The appearance of lymph nodes in the axilla or subcutaneous metastases will upstage the patient to stage IV disease when malignant cells are found at fine-needle biopsy. Additional CT or PET scans can be omitted in these cases.

Clinical signs of cyanosis, weight loss, paraneoplastic syndromes, comorbidities, low-performance status, medication use, and the psychological condition of the patient are important factors in the process of final treatment planning.

Radiological Examinations

Information obtained from a standard chest X-ray (PA and lateral view) will be the first step in imaging studies. Localization of the primary disease and presence of atelectases or pleural effusion will help to decide on the next investigation. Although less frequently used nowadays, fluoroscopy can be of help to identify superimposed lesions, pleural lesions, a reversed movement of the diaphragm, or stenosis of one of the central airways by movement of the mediastinum during forced inspiration.

Computed tomography is the examination of choice to determine the anatomical landmarks of the tumor and to obtain information about any possible mediastinal lymph node involvement. The extent of the primary tumor can be determined, and the size of the tumor can be measured. Not always a clear discrimination can be made between actual growth into surrounding tissues, as is shown in Fig. 12.2. The appearance of post-obstructive pneumonia or atelectasis can also negatively influence the measurement. Sometimes a PET scan (see below) can be of help. For discrimination of the lymph nodes in the hilar and mediastinal region, contrast-enhanced scans are a requisite. The currently available CT scans are fast and have a high resolution that allows multiplane viewing. Coronal and sagittal images can be constructed in addition to the axial recordings and help to determine whether the primary tumor is invading the mediastinum or other vital structures (Fig. 12.3).

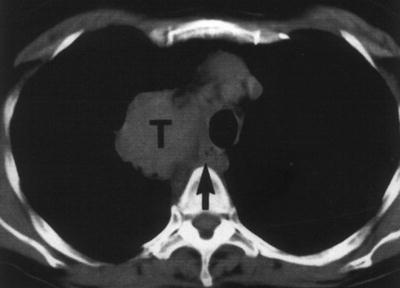

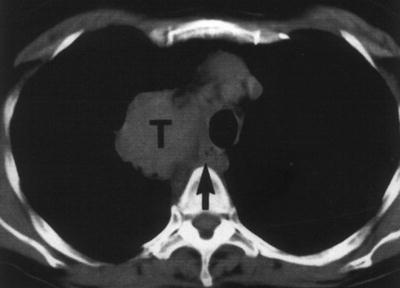

Fig. 12.2

Axial CT image of a patient with NSCLC. The tumor is located adjacent to the mediastinum. Although there is an indication that the more ventral part of the tumor (T) is probably growing into the mediastinum, the more dorsal part might be separate. The arrow indicates the location of the esophagus. This tumor is graded as minimally a T3 based on the CT image alone. Additional EUS and EBUS examination can be used to better visualize the local situation

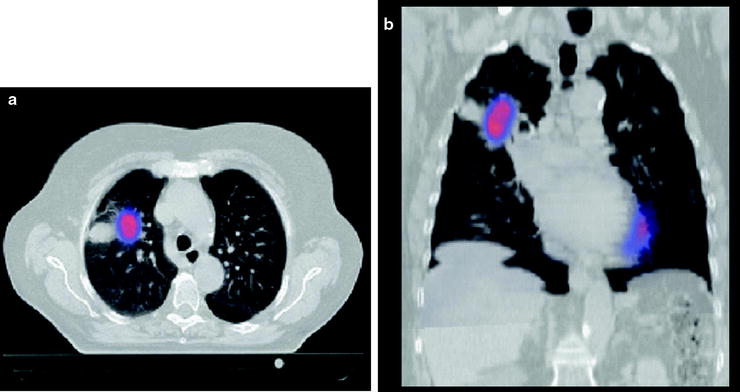

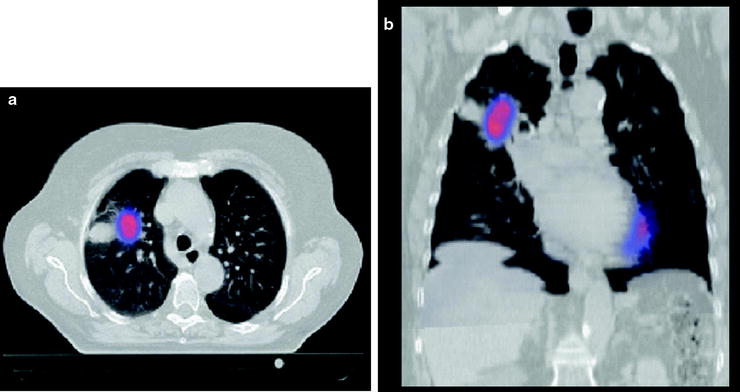

Fig. 12.3

Combination of PET and CT scans using fusion techniques. The CT and PET are made on the same time and corrected for anatomical variation in position of the patient. The axial and coronal images show a tumor-avid lesion in the anterolateral part of the right upper lobe (RUL). The CT scan shows a PET negative extension that is due to post obstruction atelectasis. Some physiologic activity of the myocardium is visible

In the following figures, examples of different stages with the plotted anatomical/radiological landmarks are presented.

Positron emission tomography is considered a standard examination for the staging of the early stages of NSCLC. Using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), the scan can identify metabolic processes in the body. This tool can discriminate between processes that have a high, low, or absent metabolic activity. When the primary tumor is FDG avid, the sensitivity to detect malignant lymph nodes or distant metastases is very high. The PET scan cannot be interpreted reliably when the primary tumor is not FDG positive or in case of a concurrent infection or other causes (Table 12.1). Concurrent infections occur often in patients with central obstruction by the tumor or due to COPD. Sarcoidosis is one of the well-known diseases that have a high FDG uptake and can mimic a tumor or positive lymph nodes. Therefore, it is important to obtain proof of one of the involved lymph nodes or lesions found in distant sites. The PET scan is not informative on the presence of ingrowth into other structures like the mediastinum when the primary tumor is centrally located. The modern scans combine CT and PET and allow projecting both images on top of each other (Fig. 12.3 and Table 12.2), enabling the physicians to decide on the further diagnostic steps (Fig. 12.4). The combination of CT scan lymph node size and PET activity improves the sensitivity and specificity.

Table 12.1

Causes of false-positive and false-negative PET

False positive | False negative |

|---|---|

Talc pleurodesis (up to 4 months after procedure) | Hyperglycemia |

Sarcoidosis | Tumor is not FDG avid |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Too long interval after FDG injection |

Wegeners’ granulomatosis | Small size (<8 mm) |

Chronic lymphatic disorders | Carcinoid tumors |

Infectious (pneumonia, abscess, fungal, mycobacterial) | Ground-glass appearance of tumor (previously known as bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma) |

Radiation pneumonitis/esophagitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|