Primary PCI at Community Hospitals without On-site Cardiac Surgery

Nancy Sinclair

Thomas P. Wharton Jr

Rationale for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at Hospitals Without Cardiac Surgery

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is now widely regarded as the reperfusion strategy of choice for patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) when delivered rapidly and expertly (1). Primary PCI results in lower rates of death, stroke, recurrent ischemia, and reinfarction compared with fibrinolytic therapy. Yet data from the National Registries of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) indicate that only 20% of patients with STEMI are treated with primary PCI in the United States (2,3). Over one-third of patients with STEMI still do not receive any type of reperfusion therapy. The emergence of primary PCI as lifesaving therapy without its effective dissemination into the community clearly represents an urgent public health problem.

Most patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) present to community hospitals without cardiac surgery programs (4). Primary PCI is seldom available at these hospitals, and many states still have regulations that restrict PCI to surgical centers. Thus patients that present to hospitals without on-site PCI have two reperfusion options: (a) fibrinolytic therapy, now widely regarded as suboptimal when immediate and expert PCI is available, or (b) rapid transfer or prehospital ambulance triage to a primary PCI center. For the appreciable number of patients that are not candidates for fibrinolytic therapy, the second option is the only one available.

Two recent randomized trials from Denmark (5) and Prague (6) compared rapid transfer to a PCI center versus local fibrinolytic therapy for patients with acute STEMI presenting to hospitals without PCI programs. (Interestingly, two of the seven PCI centers in the Prague study did not have cardiac surgery capability.) These trials, and a recent meta-analysis that included these and similar trials (7), demonstrated superior outcomes in patients with STEMI that were transferred rapidly for primary PCI compared to those randomized to fibrinolytic therapy.

Unfortunately, these strategies of early rapid transfer and prehospital ambulance triage to PCI centers have many limitations. Their use is generally confined to urban areas because the transport time must be short. Air transport, especially in the northern parts of the country, is not always a reliable option. Prehospital ambulance triage is also not an option in the 50% of AMI patients that do not arrive by ambulance (8). In addition, there could be considerable liability problems associated with interhospital transport or triage of unstable patients with AMI. Even when effective rapid transport is available, some AMI patients are too unstable to travel. In the transfer studies from Denmark and Prague, 4% and 1% of patients, respectively, were too unstable to travel, and some of these patients died; deaths during transfer also occurred (5,6). Patients too unstable to transfer, which are the highest-risk of all patients with AMI, are the very ones that should benefit the most from primary PCI if it were available at the point of first presentation. Patients with cardiogenic shock are at particular risk during interhospital transfer and often can be too unstable to transfer. Rapid primary PCI can be lifesaving in this group. The Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) study (9) demonstrated that the group randomized to mechanical revascularization within the first 6 hours of infarction had the greatest survival advantage of all subgroups.

In addition to the risk and sometimes the barrier of transfer, another problem with transfer for PCI is the delay in reperfusion. Recent data from NRMI unfortunately shows that door-to-balloon times in the United States are still 71 minutes longer for patients transferred for primary PCI than for those receiving PCI at the point of first presentation (10). Because the transfer delay in NRMI was approximately 1 hour greater than that seen in the Denmark and Prague studies, the data from these European randomized trials that showed superiority of transfer

for PCI over local fibrinolytic therapy may not even be applicable to most hospitals in the United States (11).

for PCI over local fibrinolytic therapy may not even be applicable to most hospitals in the United States (11).

Door-to-balloon times of 2.5 to 3 hours, as seen in patients transferred for PCI in the United States, are associated with a 60% increase in mortality compared to less than 2 hours (12). In fact, 85% of patients transferred for primary PCI in the NRMI registries did not receive it within 120 minutes (13). In striking contrast, nine published studies of primary PCI at hospitals with off-site backup, which include an aggregate of 5,750 patients, indicate that primary PCI at such centers can be performed within 56 to 110 minutes of first presentation (14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23). No study demonstrates median door-to-balloon times of longer than 110 minutes for nonsurgical hospitals.

As noted earlier, the risk, delay, and possibility of barrier of transfer are compounded, sometimes prohibitively, if the nearest PCI center is geographically remote.

For these reasons more and more hospitals in the United States that have cardiac catheterization laboratories but not cardiac surgery are starting to perform primary PCI on-site routinely as the treatment of choice for AMI. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association STEMI Guidelines (24) now designate primary PCI at hospitals without off-site cardiac surgical backup with a “class IIb” indication (usefulness/efficacy less well established by evidence/opinion), provided that at least 36 primary PCI procedures per year are performed at such hospitals, that the interventionalist performs at least 75 procedures per year, that procedures are performed within 90 minutes of presentation, and that there is a proven plan for rapid access to a cardiac surgical center. These guidelines also list further operator, institutional, and angiographic selection criteria for such hospitals, adapted from criteria that we have proposed (17). Our currently recommended criteria, including clinical criteria for emergent angiography, are listed in Table 13-1 Table 13-2 to Table 13-3.

There are at least 15 studies and registry reports of primary PCI at hospitals without cardiac surgery programs for off-site cardiac surgery, all of which indicate that community hospitals can deliver primary PCI safely, effectively, and rapidly, with outcomes that are similar to those reported from cardiac surgery centers (14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32). There are no reports that demonstrate the opposite. It is reasonable to expect that the benefits of increasing the speed of delivery and greater access to expert primary PCI should far outweigh any theoretical risk of having off-site rather than on-site cardiac surgery backup. The inherently lower interventional volumes of smaller hospitals may not detract from outcomes if primary PCI is performed as first-line therapy by high-volume interventionalists that regularly perform elective intervention. An institutional volume of primary PCI of more than 33 to 48 procedures per year, readily achievable at dedicated community hospital programs, correlates with improved mortality rates (12,33,34,35,36). In addition, community hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery may be able to perform primary PCI faster than larger centers both during regular working hours and during nights and weekends (37). Possible reasons for potentially greater efficiency of smaller hospitals may include more direct communication between the emergency physician and the cardiologist with less bureaucracy, decreased travel times if the catheterization team lives nearby, and greater flexibility in a catheterization laboratory schedule that may not be as congested.

There is a clear need to increase the availability of primary PCI. There is also a clear potential to accomplish this because well over 600 community hospitals in the United States have cardiac catheterization laboratories without cardiac surgery (38). Currently, PCI is being performed at certain hospitals with off-site cardiac surgery backup in 36 states, and programs are about to start in 3 others. Many of these programs are also offering nonemergent PCI, which will increase interventional volumes and thus should improve outcomes, in addition to improving access to PCI for patients with other high-risk acute coronary syndromes (39).

Table 13-1. Operator and Institutional Criteria for Primary PCI Programs at Hospitals with Off-Site Cardiac Surgery Backup | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The objective of this chapter is to propose standards, critical pathways, protocols, and care maps that will enable more of these hospitals to set up safe and effective primary PCI programs if they can meet the necessary standards. Hospitals that initiate interventional programs that rigorously follow the highest standards and protocols such as the ones that we outline here should be able to achieve outcomes that are comparable to PCI outcomes from the best high-volume surgical centers (30). Ensuring the highest quality in the delivery of PCI at all hours, which is well reflected in the achievement of rapid door-to-balloon times regardless of shift, is likely to save more lives than the theoretical advantage of having on-site cardiac surgery.

Building Critical Pathways for A Successful Community Hospital Primary PCI Program

Launching a successful program for primary PCI at a community hospital requires the commitment and collaboration of all

members of the health care team. Before starting a PCI program, cardiologists, emergency department (ED) and paramedical staff, cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL) staff, primary care physicians, cardiac nurses, cardiac rehabilitation staff, and hospital administrators need to develop a uniform standard of care for patients with AMI from the point of first patient contact through discharge planning and follow-up. Vigorous and ongoing quality improvement processes are also required to ensure a safe and effective program. The common goal is to extend all essential elements of the treatment of acute MI to patients throughout all areas of the hospital.

members of the health care team. Before starting a PCI program, cardiologists, emergency department (ED) and paramedical staff, cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL) staff, primary care physicians, cardiac nurses, cardiac rehabilitation staff, and hospital administrators need to develop a uniform standard of care for patients with AMI from the point of first patient contact through discharge planning and follow-up. Vigorous and ongoing quality improvement processes are also required to ensure a safe and effective program. The common goal is to extend all essential elements of the treatment of acute MI to patients throughout all areas of the hospital.

Table 13-2. Clinical Selection Criteria for Emergent Coronary Angiography with PCI When Indicated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The essential elements that must be established and developed include

An AMI protocol team

A primary PCI critical pathway

Operator and institutional criteria for primary PCI

Clinical and angiographic selection criteria for primary PCI and for emergency transfer for coronary bypass surgery

Position profiles, defined expectations, and training programs for CCL staff

A fine-tuned emergency triage system in the ED

A catheterization laboratory primary PCI protocol

An ongoing program to improve door-to-balloon times

An acuity-based, procedure-bumping protocol

An emergency transfer protocol and formal agreements that ensure rapid transfer to a cardiac surgery center

In-hospital AMI management pathways, to include the development of patient care protocols, standing orders, and assessment tools from admission to discharge

Processes and tracking tools for data gathering and analysis, case review, and quality assurance

Let us examine each element of this process individually. Examples are given of critical pathways and care maps for the primary PCI program at Exeter Hospital, Exeter, New Hampshire, which is a 100-bed hospital with a 25-minute travel time to the nearest cardiac surgical facility.

Table 13-3. Angiographic Selection for Primary PCI and Emergency Aortocoronary Bypass Surgery at Hospitals with Off-Site Cardiac Surgery Backup | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Establish an Acute Myocardial Infarction Protocol Team

The first step in launching a primary PCI program is to set up a multidisciplinary AMI protocol team. The goal of this team is to develop the critical pathways and care plans needed to care for the patient with AMI from the first prehospital contact all the way through to hospital discharge. These critical pathways and care plans, such as the examples included in this chapter, will have to be individualized to fit the circumstances of the hospital and thus will require multidisciplinary input. The members of the AMI protocol team should include physicians, nurses, and technical staff from the cardiology and ED departments, the emergency medical services (EMS) paramedics and technicians, the CCL, the critical care unit (CCU), the telemetry unit, cardiac rehabilitation, the blood laboratory, pharmacy and case management, along with key members of the hospital administration. The initial commitment of resources to establish an on-call system (if not already in place), to recruit sufficient well-trained CCL personnel, and to fund the stocking of the CCL with interventional equipment and supplies requires the full support of an informed hospital administration, who may need to be educated regarding the clinical value of such a program.

Develop a Primary PCI Critical Pathway

The AMI protocol team should review the current literature and standards on the care of the patient with AMI and adapt

these latest research results to their development of the central critical pathway for primary PCI. The team should incorporate newer modalities, techniques, and adjunctive medical therapies into this pathway as the current standard of care evolves. In addition, the team should review their institution’s latest outcomes, which are available at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Studies (CMS) national Web-based database (40). This resource was designed to inform consumers about the performance of local hospitals in their care of patents with AMI. Special emphasis should be placed on examining and improving the hospital’s compliance with currently established standards of care, including the percentage of patients offered reperfusion therapy, the times-to-reperfusion, rates of PCI success and complications, the percentage of AMI patients given medications such as aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and lipid-lowering agents and the percentage offered antismoking advice, cardiac teaching, and rehabilitation. Nursing and educational care plans should be revised to mirror these objectives. The team should provide educational sessions for hospital staff and referral services such as visiting nurses, skilled nursing facility staff, and cardiac rehabilitation staff to review these pathways and understand the new expectations, procedures, and equipment involved in the development of the PCI program and the follow-up utilization of evidenced-based therapies.

these latest research results to their development of the central critical pathway for primary PCI. The team should incorporate newer modalities, techniques, and adjunctive medical therapies into this pathway as the current standard of care evolves. In addition, the team should review their institution’s latest outcomes, which are available at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Studies (CMS) national Web-based database (40). This resource was designed to inform consumers about the performance of local hospitals in their care of patents with AMI. Special emphasis should be placed on examining and improving the hospital’s compliance with currently established standards of care, including the percentage of patients offered reperfusion therapy, the times-to-reperfusion, rates of PCI success and complications, the percentage of AMI patients given medications such as aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and lipid-lowering agents and the percentage offered antismoking advice, cardiac teaching, and rehabilitation. Nursing and educational care plans should be revised to mirror these objectives. The team should provide educational sessions for hospital staff and referral services such as visiting nurses, skilled nursing facility staff, and cardiac rehabilitation staff to review these pathways and understand the new expectations, procedures, and equipment involved in the development of the PCI program and the follow-up utilization of evidenced-based therapies.

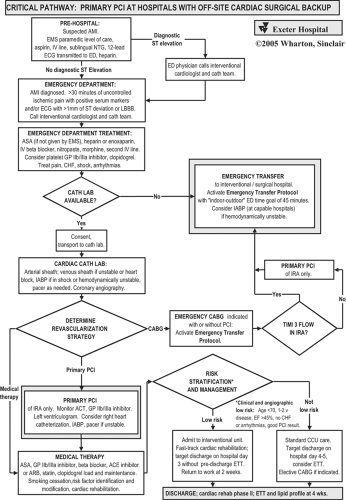

Exeter Hospital’s critical pathway for primary PCI is shown in Figure 13-1. Key features of Exeter’s pathways and care maps include protocols for the EMS paramedics in the field and the ED physicians that will optimize treatment and reduce time to reperfusion.

The cardiac catheterization procedure itself is streamlined to assess the coronary anatomy rapidly while attending to the medical treatment of the patient. With primary PCI chosen

as the reperfusion strategy, the goal of intervention is the immediate establishment of stable and brisk (TIMI grade 3) flow.

as the reperfusion strategy, the goal of intervention is the immediate establishment of stable and brisk (TIMI grade 3) flow.

After the procedure, the patient can be effectively risk-stratified and triaged to appropriate in-hospital management according to clinical and angiographic features as listed in Figure 13-1. Patients with low-risk clinical and angiographic features can avoid admission to the CCU, avoid predischarge exercise testing, be targeted for discharge on hospital day 3, and return to work within 2 weeks (41).

In the (hopefully infrequent) event that the CCL or interventionalist(s) is not available, the ED will be notified proactively. The ED physician will then discuss transfer. The decision regarding which patients with AMI should be transferred to an interventional center should be individualized and made in conjunction with the cardiologist.

Develop Operator and Institutional Criteria for Primary PCI

The AMI protocol team should develop operator, institutional, clinical, and angiographic criteria such as those listed in Table 13-1, Table 13-2 to Table 13-3 (17). The team should review local state regulations and national guidelines for primary PCI in the treatment of AMI (42). Invasive and noninvasive cardiologists, credentialing staff, and hospital administration should develop credentialing criteria based on national guidelines and regional standards. Fundamental to any interventional program is a state-of-the-art CCL, with optimal digital imaging systems, equipped with a broad array of interventional and supportive equipment (Table 13-4), and staffed by experienced and well-trained nursing and technical personnel (Table 13-5).

A commitment to provide primary PCI on a 24-hour, 7-day per week basis will avoid inconsistency in following the critical pathway for primary PCI and should reduce the potential for a lower standard of care. A single care plan for the treatment of AMI will eliminate the “door-to-decision” time; the resultant increase in procedural volumes will accelerate the learning curve for ED staff and CCL team members and operators. This will result in decreased times to reperfusion and improvement of procedural outcomes (12). A higher institutional volume of primary PCI (more than 33 to 48 procedures per year) correlates with faster door-to-balloon times and improved mortality rates (34,35).

Establish Clinical and Angiographic Selection Criteria for Primary PCI and for Emergency Transfer for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG)

Cardiologists should develop clinical and angiographic criteria for primary PCI and transfer for bypass surgery, such as those listed in Tables 13-2 and 13-3; these criteria should be documented in the patient care standards manual. We recommend immediate coronary angiography in all patients who present with a clinical picture of AMI, even if electrocardiogram (ECG) changes are not diagnostic, if they have ongoing ischemic pain for more than 30 minutes not controlled by conventional medications. Patients with AMI without ST-segment elevation on ECG represent a particularly high-risk group and are not appropriate for fibrinolytic therapy (43). These patients have greatly improved outcomes when admitted to hospitals with an early invasive rather than a conservative therapy (44). In addition, because the progression rate of necrosis in AMI varies considerably with the degree of baseline antegrade flow and collateral flow, and because the time of transition between unstable angina and AMI is sometimes hard to identify, we suggest that there be no time cutoff for reperfusion therapy if symptoms or signs of ongoing myocardial necrosis or cardiogenic shock are present (45,46,47). The goal of these criteria is to maximize coronary reperfusion opportunities while minimizing the possibility of causing new myocardial jeopardy (a “surgical emergency”) by procedures performed without on-site cardiac surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree