Primary PCI

Amr E. Abbas

Cindy L. Grines

Since the release of the first edition of Critical Pathways a tremendous amount of data has been published on primary percutaneous intervention (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation (AMI). Percutaneous mechanical reperfusion has proved to be the most effective modality for complete and sustained restoration of coronary flow in patients with AMI compared to thrombolysis (1). Transfer of patients to facilities with primary PCI, within reasonable time, was shown to be superior to thrombolytic therapy (2,3), and even superior to combined lytic and transfer protocols (4). Technically, stenting has become the standard method for managing infarct-related arteries (5,6); early administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GP IIb/IIIa) has been shown to lead to satisfactory clinical and angiographic parameters (7,8). However, the use of distal protection devices (9,10) and thrombectomy devices (11) have failed to show any benefit in randomized controlled trials. Novel techniques that have been developed to prevent damage due to myocardial reperfusion include hypothermia (12,13) and hyperbaric oxygen (14). However, those have only showed modest benefit. For patients with cardiogenic shock, PCI and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) remain the only therapeutic modalities currently recommended.

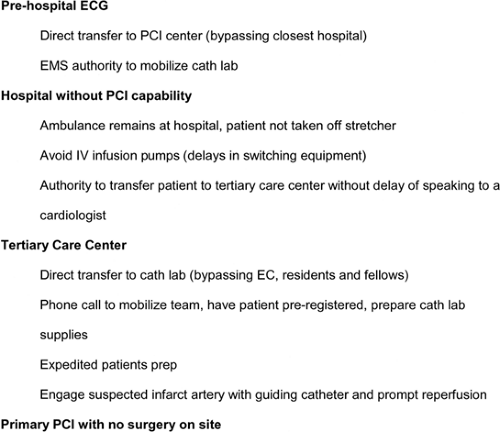

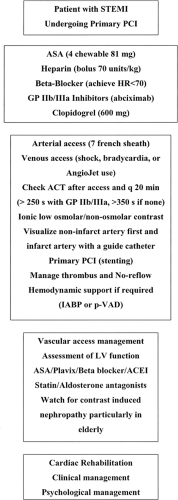

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiologists (AHA/ACC) guidelines consider as a class I recommendation PCI within 90 min from diagnosis of infarction in AMI <12 hours and carried out in centers with proven expertise. If symptom duration is <3 hours, PCI is recommended in the event that the procedure is carried out <1 hour from diagnosis. Moreover, PCI is recommended as the treatment of choice if the patient arrives >3 hours from symptom onset. PCI is also recommended in patients with heart failure or pulmonary edema and symptom onset <12 hours. On the other hand, when the onset of AMI symptoms is >12 hours, PTCA is recommended in the case of heart failure, electric or hemodynamic instability, or persistent ischemic symptoms (15). This chapter will divide the primary PCI pathways for AMI into phases: preprocedural, procedural, and postprocedural (Fig. 12-1).

Preprocedural Pathways

Comparison to Thrombolytic Therapy

In the analysis by Keeley and Grines of 23 randomized studies comparing PCI with thrombolytic therapy in AMI, primary PCI was better than thrombolytic therapy at reducing overall short-term death (7% vs. 9%; P = 0.0002), nonfatal reinfarction (3% vs. 7%; P <0.0001), stroke (1% vs. 2%; P = 0.0004), and the combined endpoint of death, nonfatal reinfarction, and stroke (8% vs. 14%; P <0.0001) (1). These results remained in favor of PCI during long-term follow-up and were independent of both the type of thrombolytic agent used and whether or not the patient was transferred for primary PCI. At our institution, all patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) <12 hours receive primary PCI.

Impact of Time to Reperfusion and Need to Transfer

Time to Reperfusion

This remains controversial because patency after PCI is the same in both early and late treated patients. Unfortunately, in the NRMI 3 and 4 analyses, the median time for transfer for AMI was 180 minutes with only 4.2% of patients treated within 90 minutes, as the guidelines recommend (16). Brodie et al evaluated patients with AMI of <12 hours’ duration, without cardiogenic shock, who were treated with primary PCI in the Stent Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (Stent PAMI) Trial (n = 1,232) to assess the effect of time to reperfusion on outcomes. Improvement in ejection fraction from baseline to 6 months was substantial with reperfusion at <2 hours but was modest and relatively independent of time to reperfusion after 2 hours. There were no differences in 1- or 6-month mortality by time to reperfusion. There were also

no differences in other clinical outcomes by time to reperfusion, except that reinfarction and infarct artery reocclusion at 6 months were more frequent with later reperfusion (17). This is different from lytic therapy, where time to reperfusion is inversely related to outcome.

no differences in other clinical outcomes by time to reperfusion, except that reinfarction and infarct artery reocclusion at 6 months were more frequent with later reperfusion (17). This is different from lytic therapy, where time to reperfusion is inversely related to outcome.

Figure 12-1. The primary PCI pathways for AMI shown in phases: preprocedural, procedural, and postprocedural. |

In a more recent analysis of four studies of 1,122 patients with AMI randomized between September 2001 and December 2003, O’Neill et al demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes in patients with AMI receiving primary PCI. The major adverse event rates were 4.5% at 30 days, with a mortality of 2% and no significant difference between anterior and nonanterior infarctions. On the multivariate analysis, door-to-balloon (P <0.0001) and onset-to-door time (P = 0.025) remained independent predictors of final infarct size (18).

Adding to the controversy, in patients with late presentation, a recent study demonstrated that in patients with AMI without persistent symptoms presenting 12 to 48 hours after symptom onset, primary PCI reduces infarct size compared to usual care (19). This suggests that the window for primary PCI may be extended beyond 12 hours. At our institution, patients with STEMI who have residual chest pain with ST-segment elevation presenting beyond 12 hours are managed by primary PCI.

Transfer

Studies that evaluated transfer to centers where primary PCI could be performed demonstrated superiority of mechanical versus pharmacological reperfusion. To date five trials have randomized STEMI patients to transfer for primary PCI versus lytic therapy. The PRAGUE 1 study (300 patients) compared three strategies in patients with AMI <6 hours from onset: (a) thrombolysis in the hospital, (b) thrombolysis during transfer for facilitated PTCA, and (c) transportation to a center for primary PTCA without thrombolytic treatment. The primary end point of death, reinfarction, and stroke at 30 days was less frequent in the transfer for PCI group (8%) compared to the second (15%) and first (23%; P <0.02). The incidence of reinfarction was significantly reduced by transportation for PCI (4). In the PRAGUE 2 study, 850 patients with AMI <12 hours were randomized to transfer for primary PCI (<120 km) versus on-site thrombolysis in the original hospital. The study ended prematurely due to excess mortality in the subgroup, which presented with ≥3 hours of symptoms, and overall 30-day mortality was 6.8% for the angioplasty group and 10% for thrombolysis group (P = 0.12). Complications only occurred during transfer (1.2%). The combined end point was less frequent in the PCI group (P <0.003), with more stroke in the thrombolysis group (P = 0.03) (3). The DANAMI 2 study compared on-site thrombolytic treatment with transfer to another center for PCI and again was stopped prematurely due to more PCI benefit. There were no deaths during transfer, and there was a 75% reduction in the relative risk of reinfarction (P = 0.0003) and decreased major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 30 days (P = 0.02) in the PCI group. Primary PCI was of benefit in the different groups, including inferior or anterior infarctions and regardless of the time from symptom onset to intervention (2). Mean time from symptom onset to randomization was 135 minutes. In Figure 12-2, our recommendations to improve transfer and reperfusion time are listed.

Adjunctive Pharmacology

Aspirin

The use of aspirin prior to primary PCI is unequivocal and should be given to all patients unless a true allergy exists (20). We provide patients with four tablets of chewable baby aspirin, which is more effective than 81 mg alone, and we avoid the enteric coated form for more rapid delivery of the drug.

Heparin

The HEAP study did not support the use of heparin as pretreatment for angioplasty (21). However, heparin is routinely initiated in the ED intravenously at a dose of 70 units/kg prior to arrival to the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

GP IIb/IIIa Inhibitors

A recent meta-analysis of the studies involving GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with ST segment elevation AMI (11 trials, involving 27,115 patients) demonstrated that when compared with the control group, abciximab was associated with a significant reduction in short-term (30 days) mortality (2.4% vs. 3.4%, P = 0.047) and long-term (6 to 12 months) mortality (4.4% vs. 6.2%, P = 0.01). This was observed in patients undergoing primary PCI but not in those treated with fibrinolysis or in all trials combined. Abciximab was associated with a significant reduction in 30-day reinfarction, both in all trials combined (2.1% vs. 3.3%, P <0.001), in primary angioplasty (1.0% vs. 1.9%, P = 0.03), and in fibrinolysis trials (2.3% vs. 3.6%, P <0.001). Abciximab did not result in an increased risk of intracranial bleeding (0.61% vs. 0.62%, P = 0.62) overall, but was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding complications when combined with fibrinolysis (5.2% vs. 3.1%, P <0.001) (22). In our institution, abciximab is frequently given for ST-segment elevation AMI in the absence of contraindications. Some operators administer the abciximab bolus intracoronary. Because few data exist regarding the use of small molecular weight GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents in AMI, we do not advocate the use of eptifibatide or tirofiban for STEMI.

Thrombolytic Agents

Thrombolytics are occasionally administered prior to PCI either as a failed primary revascularization protocol (rescue PCI) or as a facilitative modality in an attempt to enhance pre-PCI TIMI flow (facilitated PCI). Three recent trials, MERLIN (23), REACT (24), and STOPAMI (25), suggested greater myocardial salvage and fewer MACE with rescue PCI compared to conservative therapy. Despite multiple recent trials CAPITAL AMI (26), BRAVE (27), ON-TIME (28), and GRACIA-1 (29), to date no trial has shown that facilitated PCI is superior to primary PCI alone. In fact, no trial has shown clinical benefit, and some trials have suggested harm. The largest trial to date, ASSENT-4, was stopped prematurely due to increased deaths, reinfarction, and MACE in the facilitated arm compared to primary PCI. Although, the AHA/ACC guidelines allowed facilitated PCI as a class IIb recommendation in high-risk patients where PCI will be delayed and there is a low risk of complications due to bleeding (15), given the data from recent trials showing harm, we do not recommend facilitation with thrombolytics. The use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors does not appear to cause harm, but these should not be used if their administration will delay transfer to the cath lab. This may be particularly a problem with the complex dosing regimens required for eptifibatide.

Clopidogrel

In patients 75 years of age or younger who have AMI with ST-segment elevation and who receive aspirin and a standard fibrinolytic regimen, the addition of clopidogrel was found to improve the patency rate of the infarct-related artery and reduce ischemic complications (30). Moreover, in the recent mega trial (COMMITT) that included over 40,000 patients with STEMI who were randomized to clopidogrel versus placebo, there was a decrease in the incidence of death and the composite incidence of death/MI/stroke with the use of clopidogrel for up to 4 weeks postdischarge. There was no increase in the incidence of major bleeding with the use of clopidogrel (31). However, it should be kept in mind that the preoperative use of clopidogrel in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABC) surgery has been shown to be associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding and blood transfusion (32). Because 90% of patients with STEMI who go to the cath lab will undergo primary PCI and, in our experience, virtually no patients with STEMI will undergo CABG in the first few days, we recommend 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel in the EC. The higher dose provides more rapid onset of action and more complete platelet inhibition. We usually continue clopidogrel for 9 to 12 months based on the results from the CURE (33) and CREDO trials (34).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree