FIGURE 15-1 Kaplan–Meier curves of 1-year mortality among patients with acute STEMI, NSTEMI, and unstable angina. (From Ndrepepa G, Mehilli J, Schulz S, et al. Patterns of presentation and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Cardiology. 2009;113(3):198–206.)

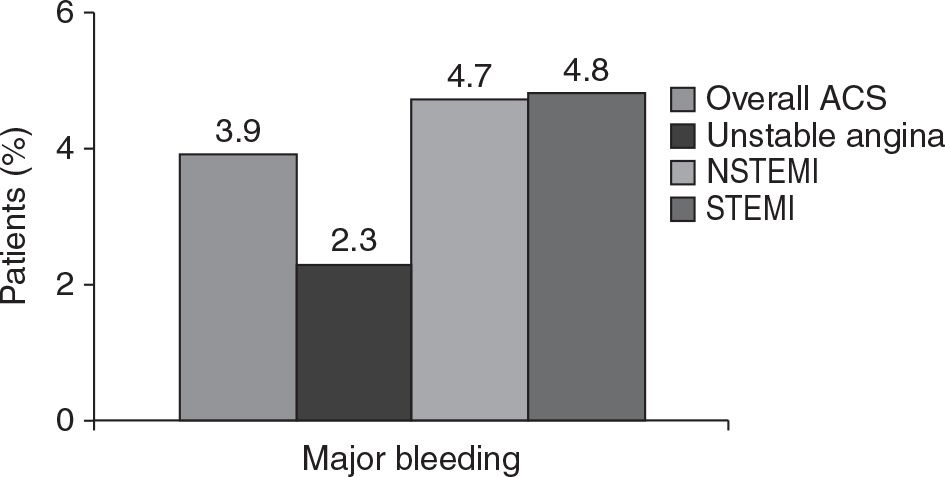

FIGURE 15-2 In-hospital major bleeding rates in unstable angina, NSTEMI, and STEMI. (From Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2003;24(20):1815–1823.)

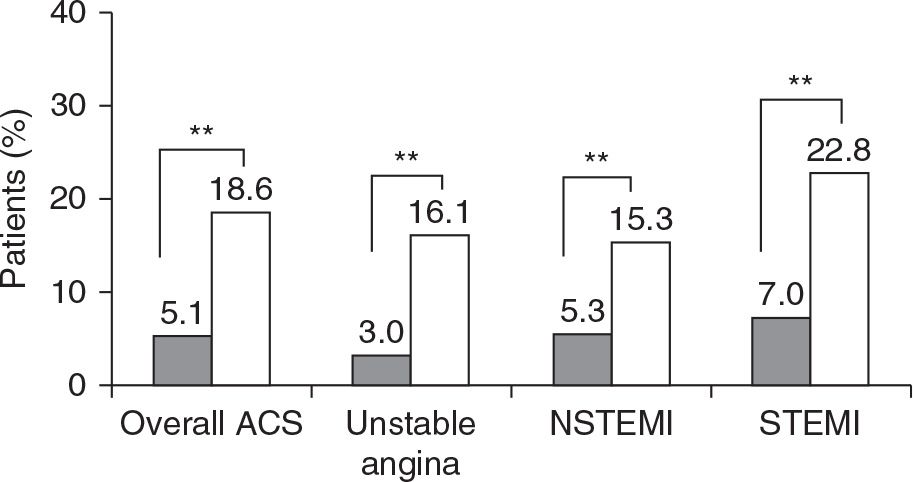

FIGURE 15-3 In-hospital death rate in patients who developed (open bars) or did not develop major bleeding (closed bars). (From Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2003;24(20):1815–1823.)

**P <0.001 for differences in unadjusted death rates.

Time Is Important in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

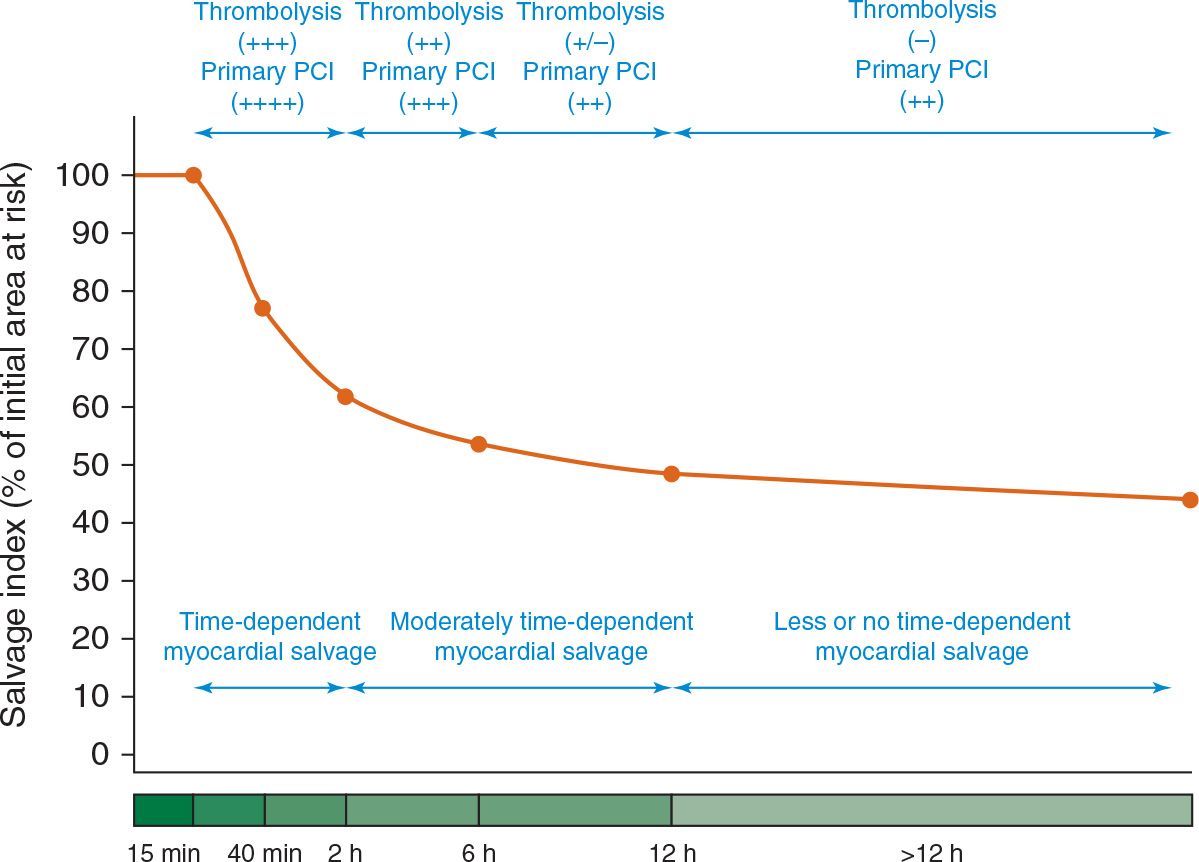

Following the occlusion of the coronary artery, myocardial damage starts soon (Fig. 15-4). Reinitiating coronary perfusion at the earliest is the cornerstone in the management of STEMI.14

There is a relationship between a delay of more than 120 minutes in door-to-balloon times and mortality in STEMI; it has been proposed to consider door-to-balloon times as a valid quality-of-care indicator, and improved door-to-balloon times have been suggested to physicians and the health system.15

There have been concerns that the use of radial access could lead to delays in door-to-balloon times compared to that with femoral access. In RIVAL trial, there was a 5-minute delay with radial access primary PCI, compared with femoral access, from the time of randomization to the completion of primary PCI (58 minutes vs 53 minutes; P = 0.0009).16 Recent sensitivity analysis using the mortality benefit demonstrated in large randomized clinical trials has suggested that the extra time associated with radial approach is unlikely to affect the clinical benefit, compared to femoral access.17

Potential Advantages of Radial Access in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Radial access can prevent femoral vascular bleeding complications such as retroperitoneal hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysms, and large hematomas. This advantage may be particularly important in patients with STEMI as they receive more potent forms of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies. Bleeding has been linked to mortality in multiple observational analyses, and so by reducing bleeding, radial access may have the potential to reduce mortality.9–11

FIGURE 15-4 The initial parts of the curve up to 2 hours were reconstructed on the basis of experimental studies. For the first 15 minutes (15 m) after coronary occlusion, myocardial necrosis is not observed. At 40 minutes (40 m) after coronary occlusion, myocardial cell death develops rapidly, and the myocardial necrosis is confluent. After this point, progression to necrosis is slowed considerably. The other part of the curve showing myocardial salvage from 2 to more than 12 hours from symptom onset is reconstructed on the basis of data from scintigraphic studies in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Efficacy of reperfusion is expressed as follows: (++++), very effective; (+++), effective; (++), moderately effective; (±), uncertainly effective; and (–), not effective. (From Schomig A, Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A. Late myocardial salvage: time to recognize its reality in the reperfusion therapy of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(16):1900–1907.)

After radial access in patients with STEMI with severe congestive heart failure, patients can sit up immediately and can potentially avoid intubation and nosocomial pulmonary infections. Finally, patients prefer radial to femoral access on the basis of published literature.12

Potential Disadvantages of Radial Access in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Owing to technical challenges with radial access (e.g., subclavian tortuosity and radial loops), there have been concerns of longer door-to-balloon times with radial access than with femoral access. There have also been concerns that owing to anatomic abnormalities, radial access could be associated with reduced guide support and differential PCI success rates. The rates of PCI success were the same and very high with both radial and femoral accesses in the RIVAL trial (95.4% vs 95.2%, P = 0.83). Similar and very high procedural success rates were also found in RIFLE-STEACS (Radial versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) and STEMI-RADIAL randomized trials.18,19

In smaller, particularly elderly, individuals, the radial artery may only be able to accommodate 5F sheaths. This may be a potential problem if thrombectomy is needed because most available thrombectomy devices are 6F compatible. However, the use of hydrophilic sheathless guiding catheter might be particularly helpful in such complex situations (see Chapter 20).

Finally, another potential disadvantage is radial artery occlusion. Most radial artery occlusions are silent but may preclude future radial access. Radial artery occlusion is discussed in further detail in Chapter 10.

Evidence Regarding the Use of Radial versus Femoral Access in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

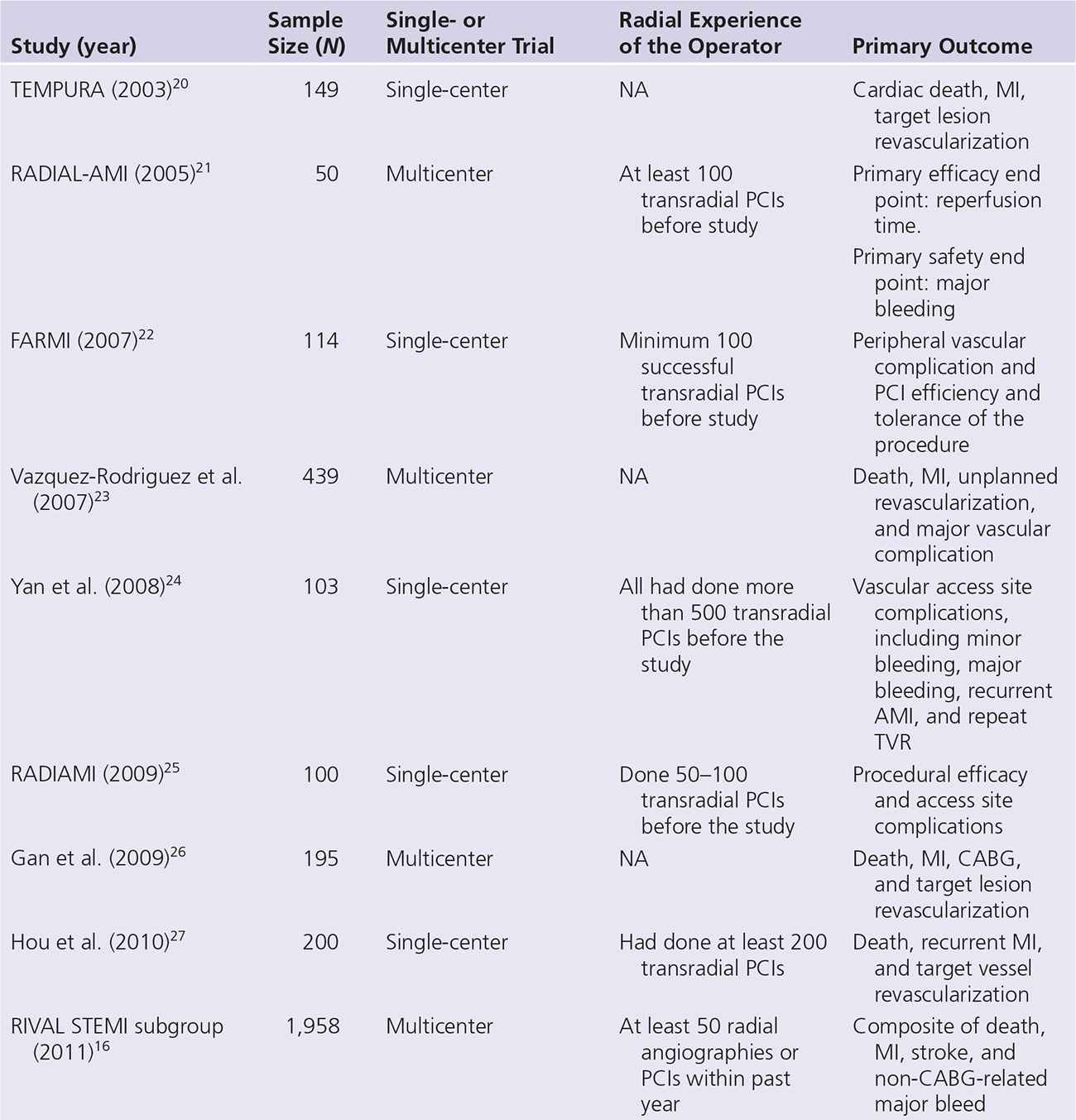

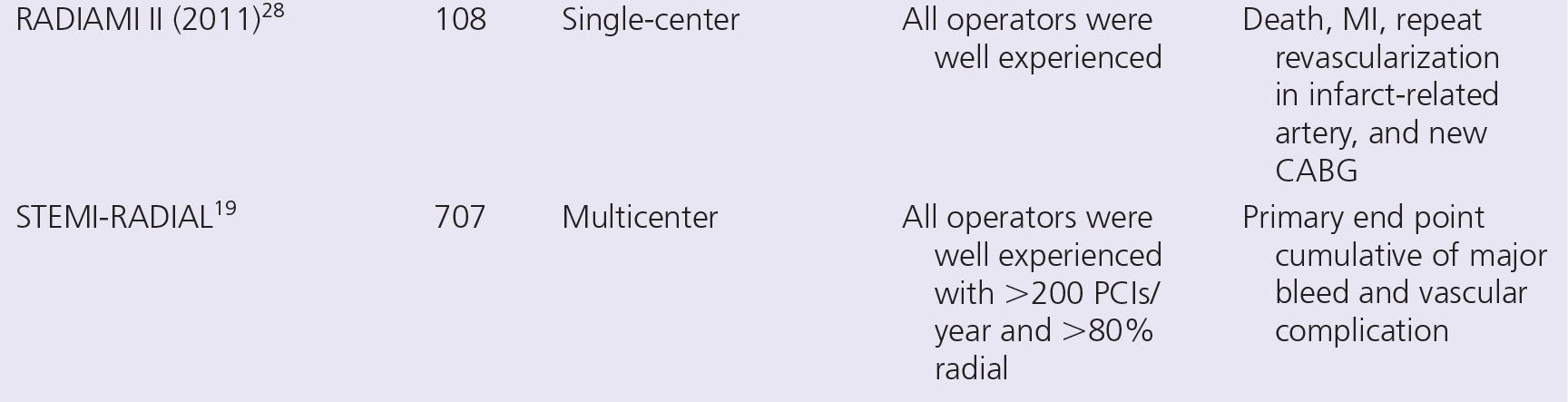

There have been at least 11 randomized trials of radial versus femoral access for STEMI PCI. The characteristics and results of these trials are listed in Tables 15-1 and 15-2. But the majority of these trials have been small single-center trials not powered for hard clinical outcomes. However, recently three large randomized trials have been published.

The first was the RIVAL trial, an international multicenter randomized trial of 7,021 patients with acute coronary syndromes that included STEMI (n = 1,958). The overall trial showed no difference in primary outcome of death, MI, stroke, or non-CABG major bleeding (Fig. 15-5). There was no difference in the rate of major bleeding utilizing RIVAL definition, but there was a 50% reduction in ACUITY major bleeding and more than 60% reduction in major vascular access site complications favoring radial access.12

TABLE 15-1 Characteristics of Randomized Trials of Radial versus Femoral Access

However, in the STEMI subgroup, radial access reduced the primary outcome (3.1% vs 5.2%, HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38–0.94, P = 0.026) as well as mortality (1.3% vs 3.2%, HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.20–0.76, P = 0.006) compared with femoral access (Figs. 15-6 and 15-7).16

The second large trial was the RIFLE-STEACS study, which enrolled 1,001 patients with STEMI undergoing PCI who were randomized to either radial or femoral access.18 The primary composite end point was the net adverse clinical event (NACE) rate, which included bleeding and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 30 days. Patients were enrolled at four high-volume radial centers in Italy. The primary outcome of NACE was 13.6% in the radial group and 21.0% in the femoral group (P = 0.003) (Fig. 15-8).18 Of note, there were lower rates of cardiac death with radial access than with femoral access (5.2% vs 9.2%; P = 0.020). In terms of bleeding complications, the bleeding rates in RIFLE-STEACS were also significantly reduced in the radial access group than in the femoral access group: 7.8% versus 12.2%, respectively (P = 0.026). The reduction in bleeding complications was driven almost entirely by a 47% reduction in access site bleeding.18 Symptom-to-balloon times for radial versus femoral access were 328 ± 301 minutes versus 322 ± 292 minutes (P = 0.752). There was a 60% reduction in access site bleeding in the radial arm when compared with that in the femoral arm.18

The most recent randomized trial of radial versus femoral access in STEMI was the STEMI RADIAL trial (N = 707), a multicenter trial performed in four high-volume radial centers in Czech Republic, with 359 patients in the femoral group and 348 patients in the radial group.19 The rate of major bleeding using HORIZONS AMI trial definition and local vascular complications were reduced by 80% with radial access (1.4% vs 7.2% in femoral group; P = 0.0001). The rate of MACE plus major bleeding was 58% lower (4.6% vs 11.0%, P = 0.0028). There was no difference in mortality (2.3% vs 3.1%, P =

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree