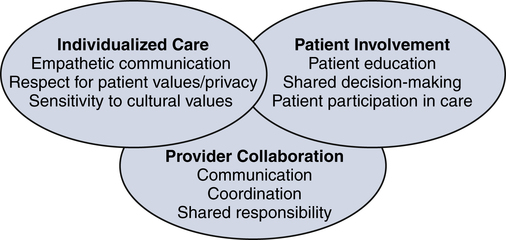

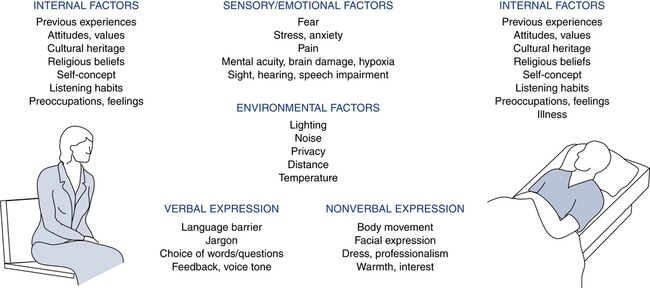

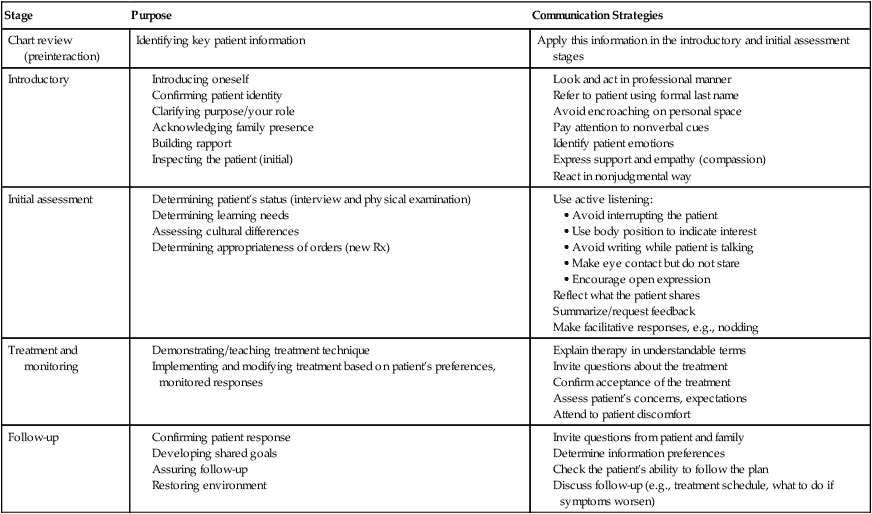

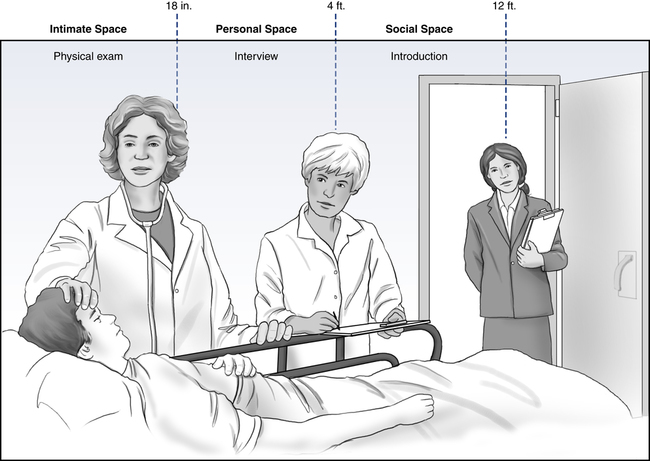

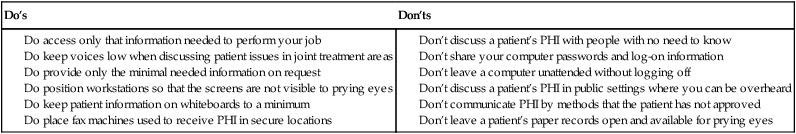

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: 1. Define patient-centered care and identify its key elements. 2. Identify the major factors affecting communication between the patient and clinician. 3. Differentiate among the stages of the clinical encounter and the communication strategies appropriate to each stage. 4. Incorporate patients’ needs and preferences into your assessment and care planning. 5. Apply concepts of personal space and territoriality to support patients’ privacy needs. 6. Employ basic rules to assure the confidentiality and security of all patient health information. 7. Identify the key abilities required for culturally competent communication with patients. 8. Specify ways to involve patients and their families in the provision of heath care. 9. Identify the steps in assessing a patient’s learning needs, including how to overcome any documented barriers to learning. 10. Explain the use of patient action plans in facilitating goal setting and patient self-care. 11. Specify steps the patient and family can take to enhance safety and reduce medical errors. 12. Identify standard infection control procedures needed during patient encounters. 13. Outline ways to assure effective communication with other providers when receiving orders and reporting on your patient’s clinical status. 14. Specify how to coordinate your patient’s care with that provided by others, as well as when transferring responsibilities to others and planning for patient discharge. 15. Identify examples of how respiratory therapists can participate effectively as a team member to enhance outcomes in caring for patient with both acute and chronic cardiopulmonary disorders. Figure 1-1 depicts the three main elements underlying patient-centered care: individualized care, patient involvement, and provider collaboration. Patient-centered care is founded on a two-way partnership between providers and patients (and their families) designed to ensure that (1) the care given is consistent with each individual’s values, needs, and preferences, and (2) patients become active participants in their own care. By improving communication and creating more positive relationships between patients and providers, patient-centered care can improve adherence to treatment plans and thus help achieve higher-quality outcomes. In addition, patient-centered care can help minimize medical errors and contribute to enhanced patient safety. Underlying patient-centered communication is empathetic and effective communication. Communication is a two-way process that involves both sending and receiving meaningful messages. If the receiver does not fully understand the message, effective communication has not occurred. As indicated in Figure 1-2, multiple personal and environmental factors influence the effectiveness of communication during clinical encounters. Attending to how each of these components may affect communication can make the difference between an effective and ineffective clinical encounter. Your use of communication techniques may differ according to the stage of interaction with a patient. Generally, a patient encounter begins with a chart review and then progresses through four additional stages: introductory, initial assessment, treatment and monitoring, and follow-up. Table 1-1 outlines the purpose of these stages and provides example strategies to help ensure effective communication during each major aspect of the patient encounter. TABLE 1-1 Stages of the Clinical Encounter To respect patients’ personal space, one needs to understand both the general and cultural implications of proximity and direct contact. Figure 1-3 depicts the three zones of space commonly associated with the bedside patient encounter. Your legal obligations regarding patient information are specified under the privacy and security rules of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). These rules establish regulations for the use and disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI). PHI is any information about health status, provision of health care, or payment for health care services that can be linked to an individual. Examples of PHI include names and addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses, Social Security and medical record numbers, and health insurance information. Under the law, patients control access to their PHI. For this reason, use or disclosure of PHI for purposes other than treatment, payment, health care operations, or public health requires patient permission. Table 1-2 provides summary guidance on key privacy and security considerations under HIPAA. TABLE 1-2 HIPAA-Related Privacy and Security Considerations

Preparing for the Patient Encounter

Individualized Care

Providing Empathetic Two-Way Communication

Stage

Purpose

Communication Strategies

Chart review (preinteraction)

Identifying key patient information

Apply this information in the introductory and initial assessment stages

Introductory

Initial assessment

Treatment and monitoring

Follow-up

Assuring Privacy and Confidentiality

Preparing for the Patient Encounter