Preoperative Evaluation of Cardiac Patients for Noncardiac Surgery

The evaluation of cardiac patients undergoing noncardiac surgery is an important part of the day-to-day practice of the consulting cardiologist. Unfortunately, poor outcomes can and do occur in high-risk patients. Therefore, predicting risk of potential nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, pulmonary embolism, or death is imperative when managing especially high-risk patients. Several risk prediction indexes have been proposed by various authors with this aim in mind. Coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery is rarely necessary, however, even among high-risk populations. In this chapter, the revised American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) Task Force on Practice Guidelines are used extensively as the primary reference for review of the literature and practice recommendations. These guidelines emphasize the importance of utilizing clinical predictors, evidence-based practice, along with a rational and common sense approach.

Approximately 30 million patients underwent noncardiac surgery in the United States in 2003. Of these, an estimated 4% had diagnosed coronary artery disease (CAD), 8% to 12% had multiple risk factors for CAD, and approximately 16% were over 65 years of age. Those at greatest risk for cardiac complications are 65 years or older with previously diagnosed CAD. This group accounts for nearly 80% of the estimated 1 million patients who suffer major cardiovascular complications annually. These cardiovascular complications cost an estimated $12 billion annually

Despite the increasing age of those undergoing noncardiac surgery, age alone represents a minor risk factor for perioperative complications. However, mortality associated with perioperative acute MI increases dramatically with advanced age. While the overall risk of suffering a postoperative MI is probably <1% with many elective operations, up to 50% of these events can be fatal. The highest risk of perioperative reinfarction occurs within the first 6 months of the index infarction and subsequently falls with time. Guidelines published by the ACC/AHA recommend that elective surgery may be performed before the 6-month time period so long as a postinfarction risk stratification has been performed. A negative stress test for ischemia or complete revascularization does reduce the risk of reinfarction with elective surgery. Nonetheless, waiting at least 4 to 6 weeks before proceeding with elective surgery represents a prudent approach suggested by these guidelines.

For patients with cardiac disease undergoing noncardiac surgery, surveillance for cardiac complications should be performed for at least 48 hours following surgery. This assessment begins with a baseline preoperative resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) for future comparison, particularly among patients with at least one clinical risk factor and/or those undergoing procedures of intermediate risk or greater. The peak risk of MI occurs within the first 3 postsurgical days but may persist for as long as 5 to 6 days. Most postoperative MIs are non–Q-wave MIs, usually detected within the first 24 hours as a result of surveillance with electrocardiographic and cardiac enzyme testing. Routine acquisition of an ECG in the immediate postoperative period has been shown to be useful in reevaluation of risk in both low- and high-risk populations after major noncardiac surgical procedures. Patients with evidence of ischemia on the immediate postsurgical ECG were found to have a higher risk of subsequent major cardiac complications. Postoperative infarctions are frequently silent, and their presence may only be revealed by the detection of new onset heart failure, hypertension, nausea, altered mental status, or arrhythmias.

PREOPERATIVE CARDIAC RISK ASSESSMENT

Surgical risk assessment encompasses patient-specific, procedure-specific, and institution-specific factors that must be identified in order to estimate individual risk and in turn outline management plans. Variables associated with the perioperative state that require careful scrutiny include the type and urgency of operation, presence and severity of CAD, status of left ventricular (LV) function, advanced age, presence of severe valvular heart disease, significant cardiac arrhythmias, comorbid medical conditions (e.g., cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease), and overall functional status.

Clinical Markers of Increased Risk

Perioperative cardiovascular risk can be stratified further into major, intermediate, and low-risk categories. Acute conditions that often require hospitalization carry more risk than stable chronic conditions. For example, decompensated heart failure would be considered a major risk predictor, likely to require further evaluation and therapy, whereas compensated heart failure would be considered an intermediate-risk condition. Major clinic predictors of high risk for perioperative morbidity and mortality include unstable coronary syndromes (unstable or severe angina or recent MI), decompensated heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and/or severe valvular heart disease. Intermediate predictors include mild angina pectoris, prior MI (by history or pathologic Q waves), compensated or prior heart failure, diabetes mellitus (particularly insulin-dependent), and renal insufficiency. Notably, a history of MI is defined as an intermediaterisk factor. However, an acute (a documented MI <7 days before the exam) or recent MI (>7 days but <1 month before the exam) is considered a major predictor. Minor clinical predictors include advanced age, abnormal ECG, rhythm other than sinus, low functional capacity, history of stroke, and uncontrolled systemic hypertension.

Procedure-Specific Risks

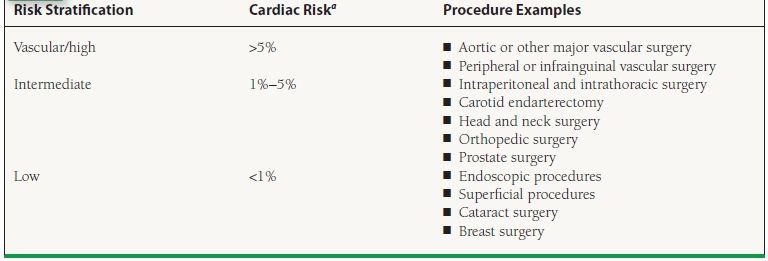

Risks associated with the planned surgical procedure require consideration and can be categorized into high, intermediate, and low-risk categories. High-risk procedures include emergency major operations (particularly in the elderly), aortic and other major vascular surgery, peripheral vascular surgery, aortic surgeries, as well as surgical procedures that are expected to be prolonged and associated with large fluid shifts and/or blood loss. Such high-risk procedures are often associated with a perioperative event rate (i.e., heart failure or MI) of over 5%. Blood loss, large intra- and extravascular fluid shifts, aortic cross clamping (in the case of aortic surgery), duration, and postoperative hypoxemia are factors believed to contribute to this increased risk. The risk of peripheral vascular surgical procedures relates to the likelihood of associated CAD in this patient population. Intermediate-risk procedures (cardiac risk generally <5%) include carotid endarterectomy, head and neck surgeries, intraperitoneal and intrathoracic surgery, orthopedic surgeries, and prostate surgery. Examples of low-risk surgeries (cardiac risk generally <1%) include endoscopic surgery, superficial procedures, breast surgery, and cataract surgery (Table 54.1).

TABLE

54.1 Cardiac Risk Stratification with Examples of Noncardiac Surgical Procedures

aReported cardiac risk, including combined incidence of nonfatal MI and death.

Modified from Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA Focused Update on Perioperative Beta Blockade Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery. et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:e13–e118, with permission from Elsevier.

Functional Capacity and Stress Testing for Preoperative Assessment of Risk

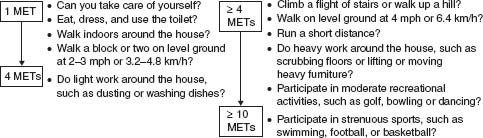

A patient’s functional capacity is a good indicator of his or her ability to safely tolerate noncardiac surgery. Estimating functional capacity can be accomplished using readily available energy requirement correlates of daily activities (Fig. 54.1). Exercise stress testing represents a particularly useful tool if it will change management among intermediate- or high-risk patients. It is important to note that noninvasive testing is not useful for patients who are at low cardiovascular risk undergoing low- or intermediate-risk procedure. Noninvasive stress testing provides an objective determination of functional status with concurrent assessment for myocardial ischemia or cardiac arrhythmias during stress evaluation. A final aim of supplemental preoperative stress testing is the provision of an objective measure of perioperative and long-term prognosis. The onset of myocardial ischemia at low exercise workload is associated with a significantly elevated risk of both perioperative and long-term cardiac events.

FIGURE 54.1 Estimated energy requirements for typical daily activities. (Adapted from Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. Guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [Committee to Update the 1996 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:542–553, with permission from Elsevier.)

A majority of patients in need of further preoperative risk stratification are either unable to exercise or have an ECG that is not interpretable. In these instances, a pharmacologic stress agent is utilized in substitute for physical activity, thereby inducing a hyperemic response, which enhances discrepancies in coronary flow, and enabling detection of myocardial ischemia. Dobutamine stress echocardiography and intravenous vasodilator myocardial perfusion scintigraphy utilizing either single positron emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) detectors represent the two most common techniques in preoperative stress testing for those who cannot exercise. The negative predictive value of these tests is high (99% for dipyridamole thallium, and 93% to 100% for dobutamine stress echo), though the positive predictive value of these tests for perioperative events is low (4% to 20% for intravenous dipyridamole thallium and 7% to 23% for dobutamine stress echocardiography). Therefore, incorporating clinical markers of risk is essential for improving the specificity and positive predictive value of these diagnostic studies. As a guideline, noninvasive testing in preoperative patients is indicated if two or more of the following are present: (a) intermediate clinical predictors (Canadian Class I or II angina, prior MI based on history or pathologic Q waves, compensated or prior heart failure, or diabetes), (b) a poor functional capacity (<4 METs), or (c) a high–surgical-risk procedure (aortic repair or peripheral vascular, prolonged surgical procedures with large fluid shifts or blood loss).

Abnormalities in thallium redistribution and coronary flow among patients with one or more clinical risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of perioperative cardiac events as compared to patients without clinical risk factors. Furthermore, postoperative events increased from 29% to 50% in a population of patients with thallium perfusion defects in the group of patients that were found to have three clinical risk factors as opposed to only one or two variables present. These data, again, highlight the importance of eliciting clinical markers of risk. Finally, the extent of ischemia (i.e., number of abnormal segments), as well as the severity of ischemia, correlates with perioperative cardiac events.

Which Stress Test Is Best?

For most outpatients able to exercise with a normal resting ECG requiring further preoperative risk assessment, treadmill exercise ECG testing represents a cost-effective assessment of functional capacity, if not a slightly less sensitive and specific assessment for myocardial ischemia compared with stress testing utilizing advanced nuclear or echocardiographic imaging. Low-risk patients include those able to exercise without cardiac ischemic symptoms beyond stage II of the Bruce protocol (>7 METs), or achieve a heart rate (HR) over 130 bpm, or over 85% age-predicted maximum HR.

Among patients unable to perform sufficient exercise (at least 4 to 6 METs) for reliable test interpretation or those with abnormal resting ECGs (e.g., LV hypertrophy, left bundle branch block, or digitalis effect), stress testing utilizing an imaging modality such as myocardial perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography is most effective. In many locations, specific expertise and familiarity with a particular stress imaging technique determines which test is used. Either stress imaging technique may be appropriate when used selectively, provided the expertise in a specific institution is satisfactory and commensurate with published investigations. Certain characteristics of these imaging techniques should be kept in mind when deciding on the ideal choice of a test. Both imaging techniques provide high sensitivity for detecting patients at risk for perioperative events, with a commensurate high negative predictive value but suffer from low specificity with corresponding low positive predictive values. Risk for perioperative events is proportional to the amount of myocardium at risk as detected by either modality. Myocardial perfusion imaging utilizing a vasodilator such as dipyridamole, adenosine, or regadenoson should be avoided in patients with significant bronchospasm, critical carotid disease, or in patients with a condition that prevents them from being withdrawn from theophylline preparations. Dobutamine should not be used as a stressor in patients with serious arrhythmias, severe hypertension, or hypotension.

Indications for Angiography

For patients with suggested or proven CAD, coronary angiography should be considered among those with high-risk results during noninvasive testing, unstable angina, and nondiagnostic or equivocal noninvasive tests in a high-risk patient undergoing a high-risk procedure. Coronary angiography may be considered in the setting of intermediate results during noninvasive testing, a nondiagnostic or equivocal noninvasive test in a patient at lower risk undergoing a high-risk procedure, urgent noncardiac surgery in a patient recovering from an acute MI, and in the setting of perioperative MI.

GENERAL APPROACH TO SUCCESSFUL PERIOPERATIVE EVALUATION OF CARDIAC PATIENTS UNDERGOING NONCARDIAC SURGERY

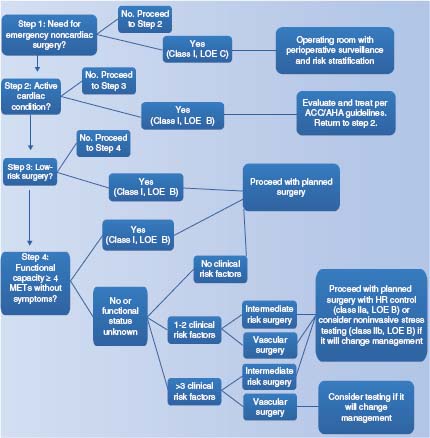

The joint ACC/AHA Task Force approach to the patient undergoing elective noncardiac surgery is based on a Bayesian strategy reliant on clinical markers, including prior CAD evaluation and treatment, functional capacity, and magnitude of the proposed surgical procedure. These general guidelines may be useful in a majority of preoperative assessment. Since publication of the original guidelines in 1996, several studies and subsequent guideline revisions have demonstrated that this stepwise approach is both efficacious and cost effective (Fig. 54.2).

FIGURE 54.2 Algorithm of preoperative cardiac evaluation for patients over age 50 years undergoing noncardiac surgery. LOE: level of evidence; METs: metabolic equivalent of task. (Modified from Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA Focused Update on Perioperative Beta Blockade Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:e13–e118, with permission from Elsevier.)