Introduction

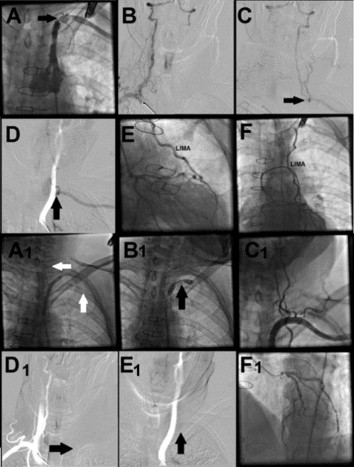

Coronary-subclavian and vertebral steal syndrome is a clinical entity in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), especially when the internal mammary artery (IMA) used as a conduit. Herein, we report 54-year-old man hospitalized with unstable angina pectoris. He had a history of CABG with left IMA to left anterior descending artery and saphenous vein graft to the right coronary artery. Physical examination revealed that weak left arm pulses, and significant systolic blood pressure difference between the left and right arms. Arterial angiographies demonstrated coronary subclavian steal syndrome from LAD to left subclavian artery and 90% stenosis of left subclavian artery which is very close to IMA vertebral artery (Fig. ABCDEF). Percutaneous revascularization (PTA) was performed for subclavian steal syndrome because of the limited antegrad flow of IMA and the very close relationship between the stenosis of and ostium of vertebral artery and IMA.

Method

6.5 F hydrophylic sheathless catheter was positioned in the left subclavian artery. 0.035-inch hydrophylic guidewire was tried to pass from microcatheter to the distal subclavian artery. After unsuccessful attempts by hydrophilic guidewire, we positioned double- lumen microcatheter to put two hydrophilic guidewires into the vertebral and distal subclavian artery. One hydrophilic guidewire was inserted into vertebral artery, and second hydrophilic guidewire were tried to pass into the distal subclavian artery while double lumen microcatheter was pull-backing from vertebral artery to the proximal subclavian artery. After succesfull wiring of both vertebral and distal subclavian arteries, we used 6.0×60 mm ballon for PTA. After PTA, there was no plaque shift to the ostiums of vertebral and left IMA. After successful deployment of 8.0×37 mm and 9.0×28 mm two ballon-expandable stents to subclavian artery, both coronary-subclavian and vertebral steal syndrome were disappeared (Fig. A1B1C1D1E1F1).

Method

6.5 F hydrophylic sheathless catheter was positioned in the left subclavian artery. 0.035-inch hydrophylic guidewire was tried to pass from microcatheter to the distal subclavian artery. After unsuccessful attempts by hydrophilic guidewire, we positioned double- lumen microcatheter to put two hydrophilic guidewires into the vertebral and distal subclavian artery. One hydrophilic guidewire was inserted into vertebral artery, and second hydrophilic guidewire were tried to pass into the distal subclavian artery while double lumen microcatheter was pull-backing from vertebral artery to the proximal subclavian artery. After succesfull wiring of both vertebral and distal subclavian arteries, we used 6.0×60 mm ballon for PTA. After PTA, there was no plaque shift to the ostiums of vertebral and left IMA. After successful deployment of 8.0×37 mm and 9.0×28 mm two ballon-expandable stents to subclavian artery, both coronary-subclavian and vertebral steal syndrome were disappeared (Fig. A1B1C1D1E1F1).

Discussion and Conclusion

The revascularization of the subclavian artery stenosis very close to IMA and vertebral artery is cumbersome problem because of the risk for the abrupt flow cessation in heart and brain. Although there hasn’t been a randomized trial comparing revascularization techniques in this regard, we hypothesthezied that percutaneous revascularization compared to surgery is simple and safe method for restoring both coronary and vertebral steal syndrome because of the better and quick physiological blood flow to IMA and vertebral artery after arterial luminal opening. We also believe that if unexpected vessel closure occurs by revascularization, there is more chance to diagnose and management of these patients by catheter-based intervention compared to surgery.