Postprocedural Care after Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation

Alan Wimmer

Hakan Oral

A number of techniques have been successfully employed for radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AF) (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). The ablation strategy and the technique by which it is performed largely determine the efficacy and safety of the procedure. However, postprocedural care is also very important to not only prevent and treat potential complications and improve patient safety but also to accurately assess the clinical response to the ablation procedure. Among these postprocedural issues, anticoagulation, antiarrhythmic drug therapy, cardioversion, ECG monitoring, and the recognition of complications such as pulmonary vein (PV) stenosis and atrial-esophageal fistula are discussed in this chapter.

Anticoagulation is a critically important component of intra- and postprocedural care for catheter ablation of AF. Thromboembolic events (TEs) may complicate catheter ablation of AF in approximately 1% of patients; and the majority of these occur within the first 2 weeks after the ablation (9). The mechanisms of TEs during the procedure may include: technical factors such as air embolism during catheter/sheath exchanges and irrigation of the sheaths; mechanical dislodgement of thrombi or tissue from endocardial surfaces during catheter/sheath manipulation; char and thrombus formation over ablation sites; and inadequate anticoagulation. Additional mechanisms of TEs postprocedure include: de novo thrombus formation due to postcardioversion atrial stunning (10); embolization of preexisting left atrial appendage thrombus after restoration of sinus rhythm; thrombus formation due to left atrial contractile dysfunction that may develop as a result of ablation (11); thrombus formation in asymptomatic patients with recurrent AF who may have discontinued anticoagulant therapy; and presence of systemic risk factors for TEs other than AF particularly in patients who have discontinued anticoagulation (12, 13, 14).

In our laboratory, heparin is administered intravenously (IV) as a bolus (100 U/kg) immediately after the transseptal puncture, and infused continuously throughout the procedure to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) of 300 to 350 seconds. In other laboratories, administration of heparin just prior to the transseptal puncture with the guidance of intracardiac echocardiography, and higher target levels of ACT (˜400 seconds) have been also used. After left atrial ablation, heparin infusion is discontinued once the catheters are removed from the left atrium. Sheaths are typically removed when the ACT is less than 180 seconds. Due to the risk of hypotension and allergic reactions, protamine is not routinely administered unless there is pericardial tamponade or bleeding. A typical dose of protamine to reverse anticoagulation is 1 mg of protamine for each 100 U of heparin. Patients remain off anticoagulation for 3 hours following sheath removal. Subsequently, a heparin drip is started without an initial bolus and is continued until the next morning to maintain a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 50 to 70 seconds. The outpatient dose of warfarin is resumed the evening following the procedure. Two hours after heparin is discontinued, low-molecular-weight heparin is administered SC at half the regular dose and continued until the international normalized ratio (INR) is ≥2. Oral anticoagulation is continued for at least 3 months in all patients.

In a recent study, the risk of TEs was assessed in 755 consecutive patients who underwent left atrial radiofrequency catheter ablation to eliminate their paroxysmal (n = 490) or chronic AF (n = 265) (9). Among these 755 patients, 411 (56%) had ≥1 risk factor for thromboembolic events including congestive heart failure, hypertension, age older than 65 years, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke, or transient ischemic event at baseline. An early thromboembolic event occurred in seven patients (0.9%) within 30 days in 755 patients after 929 procedures (0.8%). Late thromboembolic events occurred in 2 patients, 6 and 10 months after the ablation. One patient was in AF and was anticoagulated with a therapeutic INR. The other patient had a renal cortical infarct while being in sinus rhythm and receiving anticoagulant therapy with a therapeutic INR level. However, there was evidence of marked compromise in left atrial transport function in this patient.

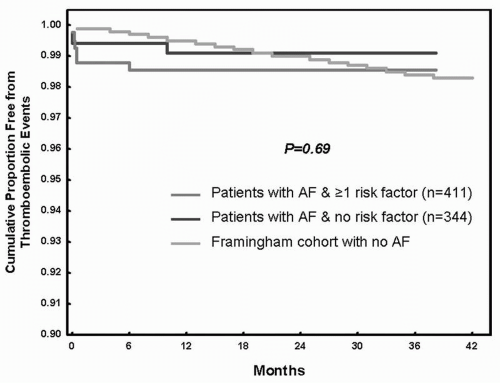

At 24 months after ablation, 99% of the patients with no baseline risk factor for stroke and 98.5% of the patients with ≥1 risk factor for stroke were free from any thromboembolic events (Fig. 21.1). The expected thromboembolic-event-free rate in an age-matched hypothetical cohort would be 99% (p = 0.69) (9). Among the patients who remained in sinus rhythm, anticoagulation was discontinued in 79% after a median of 4 months after the ablation, whereas anticoagulation was discontinued in 68% of the patients with ≥1 baseline risk factor for stroke at a median of 5 months after the ablation.

Among the variables of age older than 65 years, gender, whether episodes of AF had been paroxysmal or chronic, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, age >65 years (odds ratio, 1.82) and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack (odds ratio, 3.63) were independent predictors of continuing anticoagulant therapy after a successful ablation procedure.

The findings of this study demonstrated that anticoagulation can be safely discontinued 3 to 6 months after successful ablation in patients with no baseline risk factors for stroke and also in patients with risk factors except for a history of stroke and age older than 65 years. At present, there are insufficient data to support discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy in patients who are older than 65 years or have a history of stroke.

The role of routine antiarrhythmic drug therapy in long-term clinical efficacy after catheter ablation remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that antiarrhythmic drug therapy after catheter ablation may suppress proarrhythmia and early recurrences of AF that may occur as a result of inflammatory response to radiofrequency energy application, and thereby may facilitate reverse electroanatomic remodeling of the atrium.

In a prior series (unpublished data), circumferential PV ablation was performed in 250 consecutive patients with paroxysmal (160) and chronic (90) AF. At a mean follow-up of 10 months, there was no difference in the incidence of early or late recurrences of AF or atrial flutter among patients who were treated with an antiarrhythmic drug after the ablation and those who were not. Because there are very limited data, there is not a consensus on whether to use antiarrhythmic drug therapy routinely for several weeks after the ablation procedure.

Until more data become available, a practical strategy may be to administer antiarrhythmic drugs to only patients who develop early recurrence of AF after the ablation or to those patients who develop atrial tachycardia or flutter after the ablation. If these patients remain in AF or in other atrial arrhythmias, then cardioversion can be performed 6 to 8 weeks after the ablation. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy can then be discontinued in patients who remain in sinus rhythm. If AF or other atrial

arrhythmias recur after discontinuing antiarrhythmic drug therapy, then either drug therapy can be reinstated or a repeat ablation procedure can be considered in patients who do not want to continue antiarrhythmic drug therapy or in whom drug therapy has been ineffective.

arrhythmias recur after discontinuing antiarrhythmic drug therapy, then either drug therapy can be reinstated or a repeat ablation procedure can be considered in patients who do not want to continue antiarrhythmic drug therapy or in whom drug therapy has been ineffective.

Among the antiarrhythmic drugs, class IC agents, such as propafenone or flecainide may be considered first in patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction and who do not have coronary artery disease or marked left ventricular hypertrophy. Otherwise, amiodarone may be used. Among the other agents that can be considered are sotalol and dofetilide. Because antiarrhythmic drug therapy is planned for a few months at most, potential long-term adverse effects are usually not a concern. There are no data that have compared the efficacy of various antiarrhythmic drugs when used transiently after catheter ablation for AF.

Because early recurrences of AF or atrial flutter may be transient and do not necessarily predict the long-term clinical outcome (3,15,16), cardioversion, usually at about 2 months, may be performed to restore sinus rhythm. Cardioversion is often used in conjunction with concomitant antiarrhythmic drug therapy before contemplating a repeat ablation procedure. In a prior study, early recurrences of AF occurred in 35% of the 110 patients with paroxysmal (93) or chronic AF (17) within 2 weeks after the ablation (16). There was no difference in the prevalence of early recurrences of AF among patients with paroxysmal or chronic AF. However, among the patients who had an early recurrence, 30% remained free from atrial arrhythmias during a mean follow-up of 7 months (16). In another study, early cardioversion (within months after the ablation) was performed in 23% of the 77 patients who underwent circumferential PV ablation (5). Likewise, in two other studies, episodes of atrial flutter were transient in 30% to 50% of the patients who underwent a circumferential PV ablation procedure for AF (3,15). It is possible that early cardioversion may promote reverse atrial electroanatomic remodeling and may improve the likelihood of maintaining sinus rhythm. Multiple cardioversions may also be considered particularly in patients with recurrent atrial flutter in whom rate control with pharmacologic agents may be difficult to achieve.

Therapeutic anticoagulation for 3 to 4 weeks before and ≥4 weeks after the ablation would be appropriate. Alternatively, a transesophageal echocardiogram may be performed prior to the cardioversion when therapeutic INR levels cannot be confirmed. For patients with recurrent atrial arrhythmias after the cardioversion, repeat ablation or antiarrhythmic drug therapy with an alternative agent or rate control strategy may be considered based on patient preference.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree