Chapter 28 Pneumonia in the Non–HIV-Infected Immunocompromised Patient

Overview

The respiratory tract is continually exposed to a range of microorganisms that normal immune responses generally prevent from causing infection. Hence, it is not surprising that patients with significantly impaired immunity frequently develop lung infections. Immunodeficient patients also frequently have several other risk factors that contribute to an increased risk for development of pneumonia, including low-level microaspiration of oropharyngeal contents, mucosal damage caused by cytotoxic therapy, underlying lung damage, and poor nutrition. As a consequence, lung infections are a common and frequently serious complication in patients with significant impairment of the immune system. Pulmonary infiltrates occur in 25% of patients with neutropenia developing after chemotherapy, and up to 5% of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) will die as a result of pneumonia. The range of potential pathogens causing lung infections in immunocompromised patients is much broader than for the usual pathogens causing community-acquired pneumonia and includes organisms such as Aspergillus fumigatus and human cytomegalovirus (CMV); the diagnosis of infections due to these microbes can be difficult, and the required therapies frequently are toxic. The large number of potential pathogens and the background disease together make management of lung infection in immunocompromised patients considerably more complex, and the use of invasive diagnostic tests such as bronchoscopy frequently is necessary. This chapter focuses on the common causative pathogens and the clinical approach to pulmonary infections in patients who have been severely immunocompromised by chemotherapy, organ transplantation, or hematologic disease (Box 28-1) but not human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (discussed in Chapter 29). Pneumonia in patients with milder degrees of immunosuppression due to myeloma, low-dose cytotoxic therapy, or disease-modifying agents administered for rheumatologic conditions generally should be managed as community- or hospital-acquired pneumonia, but with recognition that the disease could be due to various opportunistic pathogens, as discussed in this chapter.

Box 28-1

Diseases and Conditions Associated With Severe Immunocompromise*

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)

Other causes of neutropenia (fewer than 1500 cells/mL)

Inherited disorders of immune function (e.g., chronic granulomatous disease, recent chemotherapy)

High-dose corticosteroid treatment (greater than 30 mg prednisolone for 21 days or longer)

Treatment with immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., tacrolimus, cyclosporine)

Treatment with cytotoxic therapy (e.g., cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate)

General Principles of the Clinical Approach

Potential pathogens causing lung infection in the immunocompromised patient are listed in Table 28-1. Empirical therapy that is active against all these possible pathogens is not feasible, especially given the potential toxicity of some treatments. Hence, the challenge in managing these patients is to (1) reduce the scope of the differential diagnosis to include the most likely problems and thus allow relatively targeted empirical therapy and (2) identify when and which type of invasive diagnostic test(s) should be used to provide the most useful data. The likely potential causative pathogens can be defined by ascertaining the following:

• The clinical and radiologic presentation

• The speed of onset of the infection

• The type, duration, and severity of the patient’s immune defect

• Positive results on microbiologic studies

• Associated factors of importance, including any recent local infective epidemics and the patient’s prophylaxis regimen, ethnic background, and travel history

Table 28-1 Range of Pathogens Commonly Associated With Pneumonia in the Non–HIV-Infected Immunocompromised Patient

| Pathogen | Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Gram-Negative Pyogenic Bacteria | |

| Escherichia coli | 6 |

| Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter spp. | 2 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | <1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | <1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 8 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 2 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | <1 |

| Gram-Positive Pyogenic Bacteria | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2 |

| Viridans streptococci | <1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 12 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 4 |

| Other Bacteria | |

| Anaerobes | <1 |

| Legionella pneumophila | 2 |

| Chlamydia spp. | 2 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | <1 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 4 |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria | <1 |

| Nocardia spp. | 2 |

| Fungi | |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | 3 |

| Candida spp. | 9 |

| Aspergillus spp. | 24 |

| Rarer molds (e.g., Mucor, Penicillium, Fusarium) | 2 |

| Endemic fungi (e.g., Histoplasma, Coccidioides) | <1 |

| Protozoa | |

| Toxoplasma gondii | <1 |

| Helminths | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | <1 |

| Viruses | |

| Cytomegalovirus | 6 |

| Herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus | 2 |

| Respiratory viruses (respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, human metapneumovirus) | 8 |

Modified from Rañó A, Agustí C, Jimenez P, et al: Pulmonary infiltrates in non-HIV immunocompromised patients: a diagnostic approach using non-invasive and bronchoscopic procedures, Thorax 56:379–387, 2001.

The exact type of immune defect is determined by a combination of the disease and the treatment received and, fortunately, can generally be predicted (Table 28-2). The three main categories of immune defect are absolute or functional neutropenia, defects in cell-mediated immunity, and deficiencies in antibody responses (a clinically less severely affected category). Each is associated with a particular range of pathogens (see Table 28-2). Patients with neutropenia are mainly at risk for infection with extracellular pathogens such as pyogenic bacteria and filamentous fungi. Defects in cell-mediated immunity tend to predispose affected patients to development of infections with intracellular pathogens such as viruses and mycobacteria, as well as some unusual extracellular infections such as Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). Deficiencies in antibody responses result in a high incidence of infections due to encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and to herpesviruses. Individual patients may have a combination of these immune defects; for example, lymphoma can cause impairment of cell-mediated immunity that can be combined with neutropenia if the patient receives chemotherapy.

Table 28-2 Type of Immune Defect According to Disease/Treatment and Range of Pathogens Commonly Associated With Infections in Patients with Such Immune Defects

| Immune Defect | Cause | Associated Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia/functional neutrophil defects | ||

| Cell-mediated immunity | ||

| Antibody deficiency |

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

* Allografts up to 1 month, autografts usually less than 14 days.

† Patients usually have a normal neutrophil count but have defects in their function and/or a poor response to infection.

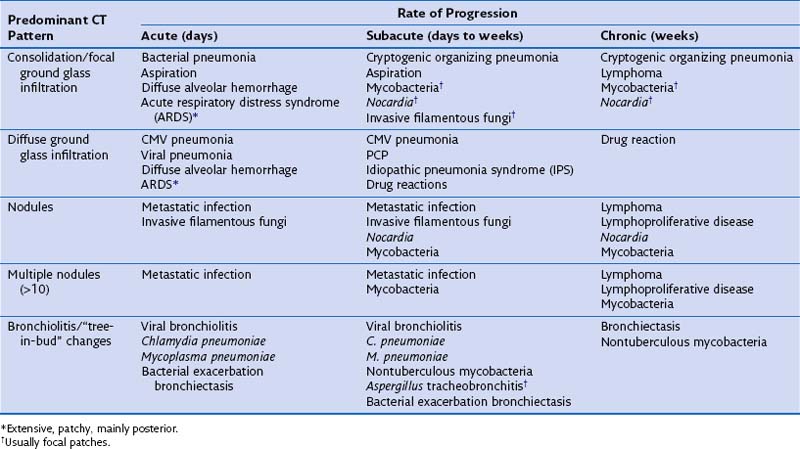

By combining the clinical pattern of presentation with knowledge of the patient’s immune defect, a differential diagnosis of likely pathogens can be suggested. For example, infections developing rapidly over 1 to 3 days with a marked rise in serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), pronounced fever, and focal radiologic changes are very likely to be due to infection with pyogenic bacteria. In a patient with a defect in cell-mediated immunity, however, widespread ground glass infiltrations in both lungs developing over several days could represent CMV pneumonitis or PCP. In general, the more severe and prolonged the immune defect, the greater the range of possible causative pathogens and the less typical the clinical presentation for a particular pathogen, prompting the need for early invasive investigation if the initial therapy is failing to effect improvement. Furthermore the character of the disease can be dictated by the severity of the immune defect. For example, infections due to filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus progress faster with increasing severity of neutropenia, but may regress and become more focal when the neutrophil count recovers. Table 28-3 shows the common conditions that should be considered for different presentations of lung complications in immunocompromised patients. Many patients will be found to have dual pathologic processes, either involving two separate pathogens or with simultaneous noninfective (fluid overload being the most common) and infective problems, which will be responsible for separate elements of the clinical picture.

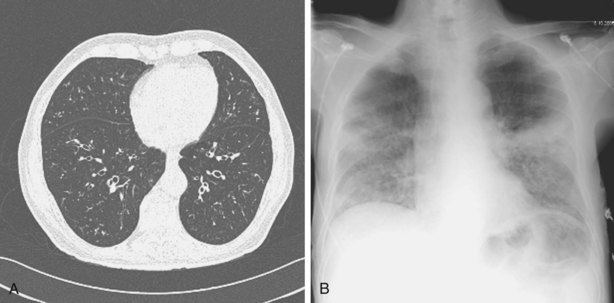

Table 28-3 Differential Diagnosis for Computed Tomography (CT) Pattern and Rate of Development of Clinical Problem

Other important factors that need to be taken into account include the patient’s present antibiotic prophylaxis regimen, travel history, and ethnic background. A patient compliant with co-trimoxazole prophylaxis will rarely develop PCP, and fluconazole prophylaxis predisposes to non-albicans Candida infection. Patients with certain ethnic backgrounds or a pertinent travel history are more at risk of TB, endemic mycoses such as histoplasmosis, or parasitic diseases such as disseminated strongyloidiasis. Finally, the patient’s background lung structure and function should be considered, because existing structural abnormalities may make certain pathogens more likely. For example, bronchiectasis could predispose affected persons to pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa (Figure 28-1), and preexisting lung cavities to Aspergillus infection.

Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Protocols

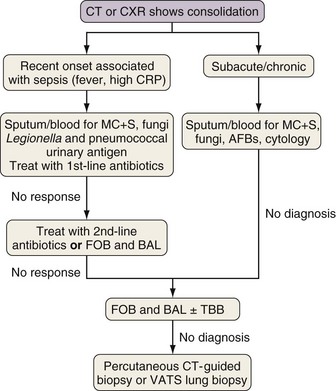

All patients with suspected new lung infection require blood and sputum cultures, as well as routine blood tests, and in many cases nasopharyngeal aspirate studies for identification of viruses, assessment of CMV status, and serum testing for fungal antigens (galactomannan or β-D-glucan). An important question for the respiratory physician is when to utilize more invasive investigations, either bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and possibly transbronchial biopsy, percutaneous radiologically guided biopsy, or, on occasion, surgical biopsy, usually video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Which test should be used and when will depend to a large extent on the type of radiologic presentation—consolidation, diffuse ground glass infiltrates, tree-in-bud changes, and nodules—in accordance with the algorithms for each provided in Figures 28-2, 28-4, 28-6, and 28-7, respectively. These suggested protocols balance the likelihood and necessity of a positive yield against the clinical probability that a particular disease will be identified with the potential complications of the investigations. These protocols are for general guidance; atypical presentations and dual pathology are not uncommon, and an individual patient often will require a modified approach. Immunocompromised patients are also at high risk for development of a range of noninfective causes of lung disease, including pulmonary edema, idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS), and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (see Chapter 59). These conditions should always be considered in the differential diagnosis for new lung disease. The protocols are discussed in detail next.

Investigation of Consolidation

Rapidly developing focal consolidation usually is due to bacterial pneumonia and initially can be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics (Figure 28-2). The most likely reason for a lack of improvement in the patient’s condition within 48 to 96 hours is infection with bacteria resistant to first-line antibiotics. At this point, treatment with second-line antibiotics effective against likely resistant organisms should be started. Consideration also should be given to starting antibiotics that are effective against MRSA and anaerobic pathogens if this has not been done already. In patients at high risk for invasive fungal infection, especially those with CT evidence of associated nodular disease or patchy or infarct-shaped consolidation, failure of first-line therapy warrants testing for fungal antigens (galactomannan or β-D-glucan) and either fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) with BAL or percutaneous CT-guided biopsy (mainly for evaluation of dense consolidation adjacent to the pleura). These investigations also will be necessary in patients whose pneumonia fails to respond to second-line antibiotic therapy or those with subacute or chronic consolidation in whom sputum microbiologic or cytologic testing is nondiagnostic. With progressive disease and lack of a definitive diagnosis after the foregoing tests, surgical biopsy should be seriously considered.

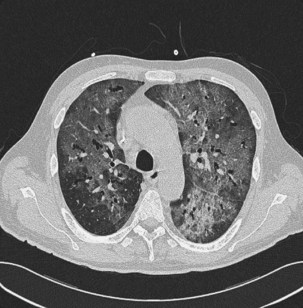

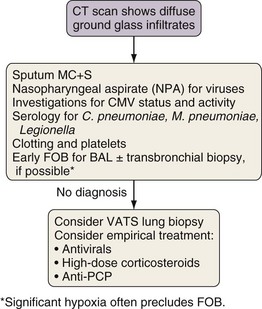

Investigation of Diffuse Ground Glass Infiltration

The differential diagnosis for ground glass infiltrates and centrilobular nodules (Figures 28-3 and 28-4) is wide in scope and includes CMV infection, viral pneumonias, PCP, extensive bacterial infection, and noninfective causes such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), drug toxicity, and IPS associated with HSCT (see Chapter 77). As a consequence, unless nasopharyngeal aspirate studies identify a respiratory viral infection, early FOB with BAL and, if possible, transbronchial biopsy should be attempted. Often, however, these patients are markedly hypoxic, increasing the risk associated with the procedure. Negative results on FOB do not exclude infective causes, and a decision then needs to be taken about empirical treatment versus VATS lung biopsy. CT-guided biopsy for investigation of diffuse lung disease carries a high risk of complications coupled with low diagnostic yield and therefore is not appropriate in this setting.