Pleural Disease Due to Collagen Vascular Diseases

RHEUMATOID PLEURITIS

Rheumatoid disease is occasionally complicated by an exudative pleural effusion that characteristically has a low pleural fluid glucose level.

Incidence

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have an increased incidence of pleural effusion. In a review of 516 patients with RA, Walker and Wright (1) found 17 cases of pleural effusions (3.3%) without other obvious causes (1). Pleural effusions were more common in men (7.9%) than in women (1.6%). These authors also found a high incidence of chest pain in their patients with RA; 28% of the men and 18% of the women gave a history of pleuritic chest pain (1). In a separate study, Horler and Thompson (2) studied 180 patients with rheumatoid disease and found that 9 (5%) had an otherwise unexplained pleural effusion. In this latter study, 8 of 52 men (15%) but only 1 of 128 women (1%) had rheumatoid pleural effusions.

Pathologic Features

Examination of the pleural surfaces in patients with rheumatoid pleuritis at the time of thoracoscopy reveals a visceral pleura with varying degrees of nonspecific inflammation. In contrast, in most cases the parietal pleural surface has a “gritty” or frozen appearance. The parietal surface looks slightly inflamed and thickened, with numerous small vesicles or granules approximately 0.5 mm in diameter (3).

Histopathologically, the most constant finding is a lack of a normal mesothelial cell covering (3). Instead there is a pseudostratified layer of epithelioid cells that focally forms multinucleated giant cells of a type different from those of Langerhans or foreign body giant cells (3). The histologic features in nodular areas are those of a rheumatoid nodule with palisading cells, fibrinoid necrosis, and both lymphocytes and plasma cells (4,5). This picture is virtually diagnostic of rheumatoid pleuritis. However, even with tissue obtained from open thoracotomy, this specific histologic picture may not be seen (6). At times, the thickened pleura contains cholesterol clefts (5).

Clinical Manifestations

Rheumatoid pleural effusions classically occur in the older male patient with RA and subcutaneous nodules. Almost all patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions are older than 35 years of age, approximately 80% are men, and approximately 80% have subcutaneous nodules (1,2,6,7). Typically, the pleural effusion appears when the arthritis has been present for several years. When two series totaling 29 patients are combined (1,7), the pleural effusion preceded the development of arthritis in 2 patients by 6 weeks and 6 months, occurred simultaneously (within 4 weeks) with arthritis in 6 patients, and occurred after the development of arthritis in the remaining 21 patients. In this last group of patients, the mean interval between the development of arthritis and the pleural effusion was approximately 10 years.

The reported frequency of chest symptoms in patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions has varied markedly from one series to another. In one series of 24 patients, 50% of the patients had no symptoms referable to the chest (8). In a second series of 17 patients,

15 complained of pleuritic chest pain (1), whereas in a third series, 4 of 12 complained of pleuritic chest pain, and of these, 3 were febrile (7). Other patients complained of dyspnea secondary to the presence of fluid. In one reported patient, the pleural effusion was large enough to cause respiratory failure (9).

15 complained of pleuritic chest pain (1), whereas in a third series, 4 of 12 complained of pleuritic chest pain, and of these, 3 were febrile (7). Other patients complained of dyspnea secondary to the presence of fluid. In one reported patient, the pleural effusion was large enough to cause respiratory failure (9).

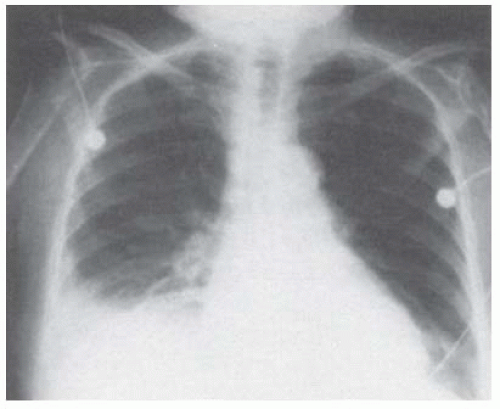

The chest radiograph in most patients reveals a small-to-moderate-sized pleural effusion occupying less than 50% of the hemithorax (Fig. 21.1). The pleural effusion is most commonly unilateral, and no predilection exists for either side (6). In approximately 25% of patients, the effusion is bilateral (1). The effusion may eventually alternate from one side to the other or may come and go on the same side. As many as one third of these patients may have associated intrapulmonary manifestations of RA (1). PET scans of patients with rheumatoid pleuritis show intense pleural uptake (10).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a rheumatoid pleural effusion is not difficult if the patient is a middle-aged man with RA and subcutaneous nodules.

Pleural Fluid Examination

Examination of the pleural fluid is useful in establishing the diagnosis because the fluid is an exudate characterized by a low glucose level (<40 mg/dL), a low pH (<7.20), a high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (>700 IU/L or >2 times the upper limit of normal for serum), low complement levels, and high rheumatoid factor titers (>1:320), which are at least as high as those in serum (7) (see Chapter 7). Occasionally, the pleural fluid glucose is not reduced when the patient is first seen, but serial pleural fluid glucose determinations reveal progressively lower pleural fluid glucose levels. In the patient with arthritis and pleural effusions, the main differential diagnosis is between rheumatoid pleuritis and lupus pleuritis. Patients with lupus pleuritis have higher pleural fluid glucose levels (>60 mg/dL), higher pleural fluid pH (>7.35), and lower pleural fluid LDH levels (<500 IU/L or <2 times the upper limit of normal for serum) than patients with rheumatoid pleuritis (7). Other immunologic tests are discussed in Chapter 7, but they are not generally recommended.

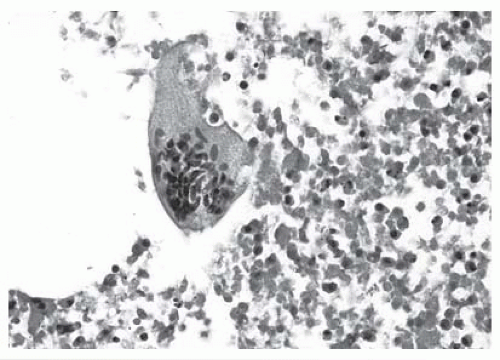

The pleural fluid differential can reveal predominantly polymorphonuclear or mononuclear leukocytes, depending on the acuteness of the process. The cytologic picture from most patients with rheumatoid pleural effusion is suggestive of the diagnosis (8). The cytologic picture with rheumatoid pleuritis is characterized by three distinct features: (a) slender, elongated multinucleated macrophages; (b) round giant multinucleated macrophages (Fig. 21.2); and (c) necrotic background material (8). When Naylor (8) reviewed the cytologic picture of 24 patients seen at the University of Michigan over a 32-year period with rheumatoid pleuritis, the pleural fluid from each patient had at least one of the three characteristics mentioned in the preceding text. Twenty-three fluids demonstrated granular necrotic material, 17 multinucleated giant macrophages, and 15 elongated macrophages (8).

These features were not seen in any of 10,000 other pleural fluids due to diverse causes (8).

These features were not seen in any of 10,000 other pleural fluids due to diverse causes (8).

FIGURE 21.2 ▪ Multinucleated giant cell on a background of amorphous material, which is characteristic of pleural effusions secondary to rheumatoid pleuritis (b/w version of Figure 7.6). |

The pleural fluid from patients with rheumatoid pleuritis may contain “ragocytes” or RA cells. The term ragocyte was coined by Delbarre et al. (11) who described small, spherical, cytoplasmic inclusions in neutrophilic leukocytes and occasionally in monocytes in unstained wet films of the sediment obtained from the synovial fluid of patients with various types of arthritis. These inclusions were reminiscent of raisin seeds; hence, the adoption of the prefix rago, which is derived from the Greek word for grape. The inclusion bodies have been shown to represent phagocytic vacuoles or phagosomes, which are of greater size than normal lysosomes of granular leukocytes (12). The presence of these cells is not useful diagnostically because pleural effusions of other etiologies, particularly those with a low glucose level, contain these cells (8,13).

Concomitant Infection

When a patient is seen with RA and a pleural effusion characterized by a low glucose level (<20 mg/dL), a low pH (<7.20), and a high LDH level, one must rule out pleural infection, which can produce pleural fluid with the same characteristics (see Chapter 12). Hindle and Yates (14) first reported a pyopneumothorax in a patient with a rheumatoid pleural effusion. At thoracotomy, it was found that a necrobiotic nodule in the visceral pleura had broken down, producing a bronchopleural fistula. Jones and Blodgett (15) subsequently reported that 5 of 10 patients with rheumatoid pleural effusion followed for a 5-year period developed empyemas. These investigators found that empyemas were more common in patients who had been treated with corticosteroids, and they attributed the pleural infection to the creation of a bronchopleural fistula through necrobiotic subpleural rheumatoid nodules.

When a patient with an apparent rheumatoid pleural effusion is seen, it is important to obtain both aerobic and anaerobic cultures of the pleural fluid. In addition, the pleural fluid should be centrifuged, and the sediment should be Gram stained because stains made in this manner are more sensitive than those made on uncentrifuged pleural fluid.

Glucose Levels

The most striking characteristic of the rheumatoid pleural effusion is its low glucose content. In a review of 76 patients with rheumatoid pleuritis, 48 (63%) had pleural fluid glucose levels below 20 mg/dL, whereas 63 (83%) had pleural fluid glucose levels below 50 mg/dL (6). The explanation for the low pleural fluid glucose in this condition is not known precisely. If the serum level of glucose is increased in patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions, little change is seen in the pleural fluid glucose levels (16,17,18), but similar results are obtained in patients with low pleural fluid glucose levels from other diseases (19). In contrast, when patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions are given oral urea (18) or intravenous d-xylose (17) loads, the pleural fluid and serum levels of these substances equilibrate over several hours.

Carr and McGuckin (18) have suggested that the rheumatoid inflammatory process alters the normal state of one or more enzymes that constitute the carbohydrate transport mechanism of cellular membranes. This interpretation should be viewed with some caution. The relationship between the serum and pleural fluid glucose levels is dictated not only by the ease with which glucose passes from the serum into the pleural fluid but also by the rate at which the pleural surfaces and fluid use the glucose. Because the pleural fluid glucose level falls within 30 minutes from 2,000 to 236 mg/dL after the intrapleural injection of glucose in patients with rheumatoid pleuritis (16), there must be either rapid glucose uptake by the pleura or no great barrier to its diffusion.

The pleural surfaces with rheumatoid pleuritis appear to be active metabolically, as manifested by the high pleural fluid LDH and the low pleural fluid glucose levels, although the metabolic activity of rheumatoid pleural fluid is virtually nil even when glucose is added (17). The thickened pleura in rheumatoid pleuritis probably limits the movement of glucose into the pleural space, and because glucose consumption by the pleural surfaces is high, an equilibrium is formed in which the pleural fluid glucose level is much lower than the serum glucose level.

Cholesterol Levels

Another interesting characteristic of rheumatoid pleural effusions is their tendency to contain cholesterol crystals or high levels of cholesterol. Ferguson (5) first reported on two patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions in whom the pleural fluid contained numerous cholesterol crystals. Subsequently, Naylor (8) reported that 5 of 24 rheumatoid pleural fluids (21%) contained cholesterol crystals. Some rheumatoid pleural effusions contain high levels of cholesterol without cholesterol crystals (6).

Lillington et al. (6) measured the lipid levels in seven rheumatoid pleural effusions and found levels

above 1,000 mg/dL in four of the seven fluids. One of the two patients whom I have seen with cholesterol crystals in the pleural fluid had rheumatoid pleuritis. The cholesterol crystals impart a sheen to the fluid when viewed with the naked eye under proper lighting. High cholesterol levels make the pleural fluid turbid. The significance of the presence of high levels of cholesterol or cholesterol crystals in the pleural fluid is unknown. Cholesterol pleural effusions are discussed more extensively in Chapter 26.

above 1,000 mg/dL in four of the seven fluids. One of the two patients whom I have seen with cholesterol crystals in the pleural fluid had rheumatoid pleuritis. The cholesterol crystals impart a sheen to the fluid when viewed with the naked eye under proper lighting. High cholesterol levels make the pleural fluid turbid. The significance of the presence of high levels of cholesterol or cholesterol crystals in the pleural fluid is unknown. Cholesterol pleural effusions are discussed more extensively in Chapter 26.

Biopsy

Closed pleural biopsies have a limited role in the diagnosis of rheumatoid pleuritis. Although a pleural biopsy specimen may reveal a rheumatoid nodule diagnostic of rheumatoid pleuritis in an occasional patient, the pleural biopsy usually reveals only chronic inflammation or fibrosis. Pleural biopsy is not recommended in the typical case of rheumatoid pleuritis. In atypical cases, however, such as in patients without arthritis or in those with a normal pleural fluid glucose level, thoracoscopy, or pleural biopsy should be performed to rule out malignant disease and tuberculosis.

Prognosis and Treatment

The natural history of rheumatoid pleuritis is variable. In the series of Walker and Wright (1), 13 of 17 patients (76%) had spontaneous resolution of their pleural effusions within 3 months, although 1 of the 13 patients had a subsequent recurrence. One patient had a spontaneous resolution after 18 months of observation, whereas another had a persistent effusion for more than 2 years. One patient developed progressive severe pleural thickening and eventually had to undergo a decortication. The last patient developed an empyema.

Little information is available in the literature on the efficacy of therapy in rheumatoid pleural disease. Some patients have appeared to respond to systemic corticosteroids (1), whereas in others no beneficial effects were observed (20,21,22). The degree of activity in the pleural space and in the joints is not necessarily parallel. In one report, the administration of methotrexate was associated with improvement in the arthritis but also with the development of a pleural effusion (23). The main goal of therapy should be to prevent the progressive pleural fibrosis that may necessitate a decortication in a small percentage of patients (1,4,21,24,25). There are no controlled studies evaluating the efficacy of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of rheumatoid pleural effusion. It is recommended that patients be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin or ibuprofen for 8 to 12 weeks initially. If the pleural effusion persists and if the joint symptoms are not well controlled, then appropriate therapy should be directed toward the rheumatologic problem. If the only symptomatic problem is the pleural disease, then the patient should have a therapeutic thoracentesis and possibly an intrapleural injection of corticosteroids. There have been two reports concerning the intrapleural injection of corticosteroids; the first (22) had two patients, and the intrapleural corticosteroids were ineffective; the second (26) had one patient who seemed to respond to one injection of 120 mg of depomethylprednisolone.

Decortication should be considered in patients with thickened pleura who are symptomatic with dyspnea. Computed tomographic examination is useful in delineating the extent of the pleural thickening. In patients with pleural effusions, the significance of the pleural thickening can be gauged by measuring the pleural pressure serially during a therapeutic thoracentesis (see Chapter 28). If the pleural pressure drops rapidly as pleural fluid is removed, the lung is trapped by the pleural disease (27), and decortication should be considered. The decortication procedure is difficult to perform in patients with rheumatoid pleuritis because it is not easy to develop a plane between the lung and the fibrous peel. Therefore, air leaks persist longer than usual after decortication (25). Nevertheless, decortication can substantially improve the quality of life of some patients with dense pleural fibrosis secondary to rheumatoid disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree