The diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia is determined according to Task Force Criteria published in 1994 that included imaging abnormalities of the right ventricle and diagnostic pathologic evaluation findings of the right ventricular myocardium by endomyocardial biopsy. These have recently been modified to include evaluation using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. In addition, quantitative criteria for the percentage of fibrosis and the decrease in myocytes have been included in the new criteria. The pitfalls of determining the presence of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia at autopsy and the difficulty in assessing the presence of this disease in family members are well illustrated in the present report. In conclusion, we have illustrated the need to subscribe to the modified criteria to avoid misdiagnosis.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) is an uncommon genetic disease principally affecting the right ventricle by fatty and fibrous tissue replacement of the myocardium. The clinical manifestations primarily result from ventricular arrhythmias such as ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) and nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia. Occasionally, sudden cardiac death will be the first event. If this occurs, it frequently and appropriately should initiate a clinical evaluation of the patient’s family members. The pitfalls of determining the presence of ARVC/D at autopsy and the difficulty in assessing the presence of this disease in family members are well illustrated in the present report.

Case Report

A 32-year-old asymptomatic woman (patient A) sought medical advice because her paternal grandmother had been diagnosed with ARVC/D at autopsy. Patient A had undergone routine electrocardiography 2 years previously and had been noted to have VPCs. Her 12-lead electrocardiographic findings were normal; the T wave was inverted in V 1 but the T waves were upright in V 2 to V 6 . The findings from a signal-averaged electrocardiogram were normal. She had excellent exercise tolerance on a stress test. Several VPCs were noted during recovery, but no sustained ventricular tachycardia was seen. A 24-hour Holter monitor showed 3,025 VPCs per 24 hours and one episode of 3 consecutive VPCs. The VPCs had a right bundle branch block pattern.

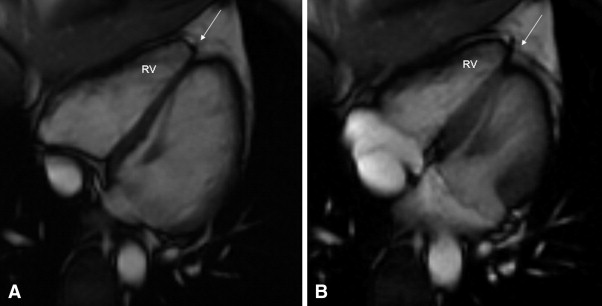

A 2-dimensional echocardiogram showed mildly redundant mitral leaflets and minimal mitral regurgitation but no mitral valve prolapse. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was interpreted at the referring institution as showing “a subtle abnormality involving the right ventricular apex. There was slightly diminished contractility and delayed enhancement involving the right ventricular apex. This could represent a mild form of right ventricular dysplasia.” These studies were sent to a tertiary referral center for evaluation. The imaging studies were interpreted by a cardiac magnetic resonance specialist with extensive experience in the interpretation of these tests in patients with suspected ARVC/D. The specialist could not find any abnormality suggestive of ARVC/D, either on the echocardiogram or CMR Images ( Figure 1 ). The patient (patient A) was reassured, and no additional studies for ARVC/D were done. No treatment was advised.

This woman related her experience with regard to the possible misdiagnosis of ARVC/D by CMR imaging to her cousin (patient B), a 27-year-old woman, who had recently been diagnosed with ARVC/D, who then sought a re-evaluation of her diagnosis. The 2 patients were first cousins with the same grandmother, who had been diagnosed with ARVC/D at autopsy. The cousin’s sister had recently died unexpectedly at age 40 and had been diagnosed with ARVC/D at autopsy. This 27-year-old woman (patient B) reported she had noted palpitations after her sister’s death.

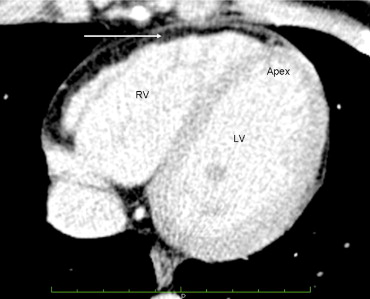

The cousin’s (patient B) electrocardiographic findings were normal. The 2-dimensional echocardiogram showed mild left ventricular enlargement. A CMR imaging study showed “fatty infiltration of the right ventricular wall.” No wall motion abnormalities were noted. The right ventricular ejection fraction was reported as 46%. A cardiac computed tomographic scan of the chest was interpreted as showing diffuse fatty infiltration of the right ventricular wall ( Figure 2 ).

The cousin (patient B) was referred to an electrophysiologist, who implanted an implantable cardioverter defibrillator owing to the family history of ARVC/D and the imaging studies that showed fatty infiltration of the right ventricular myocardium. She has not required implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy during the 9-month period since implantation. The patient expressed concern that her 4 children might be affected with ARVC/D.

The CMR imaging study and computed tomographic scan were reviewed at our tertiary medical center, and it was concluded that the left ventricular and right ventricular global systolic function were normal. Fat was seen around the right ventricle, but no fatty infiltration was present in the right ventricular myocardium ( Figure 2 ). No right ventricular wall motion abnormalities were seen. It was concluded that the imaging criteria of ARVC/D had not been met in this patient. Subsequent genetic testing of patient B was reported as negative for any desmosomal abnormality.

The records were obtained for the 2 family members who had had a postmortem diagnosis of ARVC/D. Only a death certificate was available for the grandmother who had died in 2000 at age 68. The immediate cause of death was reported as heart failure and “ARVC/D.” However, she had adenocarcinoma of the liver, with metastasis to the lungs, and also chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Carcinoma was the most likely cause of her death. No additional details were available regarding the morphology of her right ventricle.

The autopsy of the 40-year-old sister who had died suddenly and unexpectedly was reported to show fibrofatty infiltration of the right and left ventricular myocardium. The cause of death was stated to be ARVC/D. A complete cross-sectional slice of the heart, including the right and left ventricles with ventricular septum, were provided by the medical examiner and sent to the co-director of the pathology core laboratory (Padua, Italy) of a National Institutes of Health research study of ARVC/D. A large amount of fat was present in the right ventricle, but this was within physiologic limits ( Figure 3 ). The panoramic sections were stained with trichrome and did not show any evidence of fibrosis ( Figure 3 ). At high magnification, the hematoxylin-eosin stain did not show myocyte abnormalities ( Figure 3 ). It was concluded that no pathologic evidence was present for a diagnosis of ARVC/D, only fatty infiltration (adipositas cordis).