gical therapy. Revascularisation is indicated if acute ischaemia, CLI and if symptomatic on

the above.

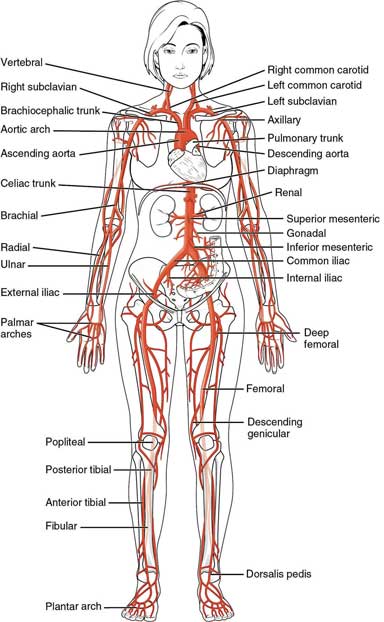

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) refers to partial or complete obstruction of the arterial blood supply to the upper and/or lower limbs. The majority of cases are secondary to long-standing atherosclerosis (chronic limb ischaemia); however, sudden deterioration may occur secondary to thrombosis or embolism (acute limb ischaemia).

Figure 15.1 – Arterial system.

15.2.1 Chronic limb ischaemia

Definition

Chronic limb ischaemia is a condition where blood supply to the limbs deteriorates with time as a consequence of progressive atherosclerotic disease, with symptoms initially on exertion but eventually at rest where it is termed ‘critical limb ischaemia’.

Epidemiology

- Incidence increases with age: 1 in 10 patients over the age of 60 have evidence of peripheral arterial disease

- Risk factors: male gender, Afro-Caribbeans, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, family history of atherosclerosis

- Critical limb ischaemia is seen in 1% of patients with PVD.

Aetiology

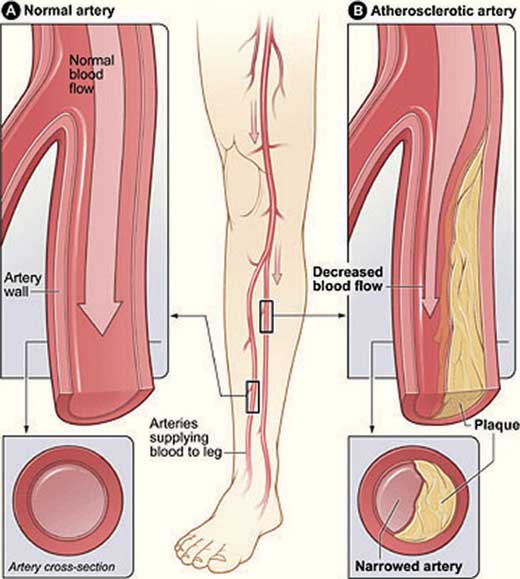

Atherosclerosis is the main disease process underlying the development of chronic limb ischaemia (refer to Chapter 7). This is accelerated by the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Pathophysiology

The main pathophysiological feature in PAD is the mismatch between the circulatory supply and the metabolic/nutrient demands of the skin and skeletal muscles. The most important factor is the atherosclerotic flow-limiting lesion. Other factors include impaired vasodilatation and exaggerated vasoconstriction secondary to dysregulation of various components, such as nitric oxide, which aids vasodilatation.

In the early stages of the disease, metabolic demands are not compromised in any circumstance, and the patient is asymptomatic. The patient may also be asymptomatic if collateral vessels are well developed. As the disease progresses, oxygen delivery is insufficient to meet metabolic demands on exertion, resulting in intermittent claudication (see below).

// Why? //

With oxygen deprivation, lactate and other metabolites accumulate as a product of anaerobic metabolism; this activates local sensory receptors and causes intermittent claudication.

Eventually multiple occlusive lesions compromise supply to the extent that metabolic demands cannot be met even at rest (critical limb ischaemia).

Clinical features

Key features

The cardinal symptoms of chronic limb ischaemia are intermittent claudication and rest pain determined by the severity of atherosclerosis and presence of collateral vessels.

Figure 15.2 – Chronic limb ischaemia.

- Asymptomatic – two-thirds of patients

- Intermittent claudication (IC)

- ischaemic-type pain (aching) on exertion (e.g. walking) that resolves promptly with cessation of activity and rest

- the location of pain depends on the site of stenosis:

– buttock and thigh pain: aorta, iliac vessels

– calf pain: femoral or popliteal vessels

– ankle and foot pain: tibial or peroneal vessels

- Leriche syndrome is the presence of erectile impotence, bilateral buttock claudication with reduced or absent femoral pulses and indicates involvement of the common or internal iliac artery

- ischaemic-type pain (aching) on exertion (e.g. walking) that resolves promptly with cessation of activity and rest

// Why? //

The gastrocnemius muscle of the calf utilises more oxygen than any other of the muscle groups in the leg. Therefore, the calf is the most commonly affected site.

- Critical limb ischaemia (CLI)

- this is the presence of pain at rest, often accompanied by:

– paraesthesia in the foot or toes

– ulceration

– necrosis and gangrene

- symptoms are exacerbated by leg elevation and relieved with leg dependency

– pain is typically worse at night, relieved by hanging the foot off the bed

- patients with diabetic neuropathy may experience little to no pain despite severe ischaemia.

- this is the presence of pain at rest, often accompanied by:

Figure 15.3 – Arterial ulcer on the left heel.

Figure 15.4 – Gangrenous foot.

Examination findings

- Absent or decreased peripheral pulses

- Bruits in aorta and groin

- Buerger’s test: elevation of the leg with the patient supine elicits ischaemia and the leg goes pale (flow fails to overcome gravity). The more severe the PAD, the lower the angle required to initiate this (Buerger’s angle)

- Rubor on dependency: after elevation of the leg, hanging the legs off the bed causes a change in colour from white to blue, and eventually to very dark red (reactive hyperaemia).

EXAM | Signs of chronic ischaemia:

|

Differential diagnoses

- Spinal stenosis: usually there is a history of back pain, worse with lumbar spine flexion

- Arthritis (hips, knees): usually occurs at rest and with activity and does not resolve quickly.

Investigations

First-line

- Blood tests

- to assess renal function and for presence of cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. lipids, glucose) and anaemia

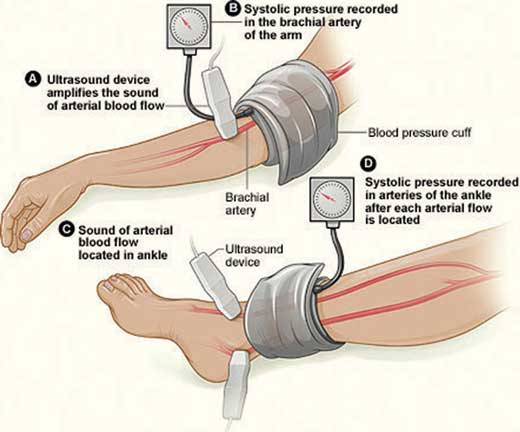

- Ultrasound: ankle–brachial pressure index (ABPI)

- an ultrasound Doppler determines the ratio between the systolic blood pressure of the ankle and the brachial artery (ankle–brachial index)

- in chronic lower limb ischaemia, the SBP at the ankle is lower than that at the brachial artery, resulting in a low ABPI (see Table 15.1)

- in stiffened arteries (calcification in diabetes mellitus and the very elderly), the ABPI may be raised (>1.4)

- strong predictor of peripheral vascular disease: sensitivity 79%, specificity 96%

- ABPI levels correlate well with severity but poorly with symptoms. A low ABPI is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality, irrespective of symptoms.

- an ultrasound Doppler determines the ratio between the systolic blood pressure of the ankle and the brachial artery (ankle–brachial index)

Figure 15.5 – Ankle–brachial pressure index measurement.

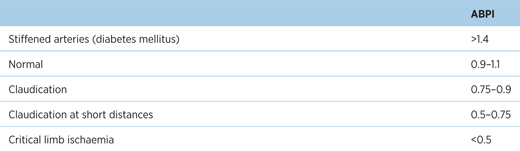

Table 15.1 – ABPI readings correlating the different severities

Second-line

Indicated if there is a normal ABPI, diagnostic uncertainty or intervention is considered.

- Duplex ultrasound assessment

- able to identify vascular lesions

- should be performed in the management of PAD

- able to identify vascular lesions

- CT or MR angiography

- Digital subtraction angiography: previously the gold standard but superseded by non-invasive imaging. It plays a role during the endovascular procedure.

Management

Aims: to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, to improve quality of life and improve walking distance.

- Lifestyle changes

- smoking cessation: reduces risk of amputation and post-op mortality

- exercise rehabilitation: supervised exercise for 3 months. It enhances muscle metabolism, and promotes vasodilatation and vascular angiogenesis. It improves walking distances, and may also improve survival

- Mediterranean diet

- smoking cessation: reduces risk of amputation and post-op mortality

- Best medical treatment

- lipid modification: diet, statins

- blood pressure control: target blood pressure <140/90 mmHg, or <130/80 mmHg in diabetic patients

- diabetic control: HbA1c <48 mmol/mol (<6.5%)

- antiplatelet therapy: aspirin is first-line in order to reduce the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and vascular death

- lipid modification: diet, statins

- Symptomatic relief of claudication

- cilostazol and naftidrofuryl are anti-claudication drugs with proven efficacy

- they improve walking distance and quality of life

- indicated in patients still symptomatic after exercise rehabilitation or those unwilling to undergo angioplasty or bypass surgery

- cilostazol and naftidrofuryl are anti-claudication drugs with proven efficacy

- Endovascular treatment: angioplasty and stenting

- this is the preferred revascularisation method in the majority, with reduced procedural morbidity and mortality compared to surgery

- indicated in CLI and where there is failure of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions in improving symptoms

- disadvantages are lower long-term patency and lack of evidence for long-term benefit over exercise rehabilitation and best medical treatment

- this is the preferred revascularisation method in the majority, with reduced procedural morbidity and mortality compared to surgery

Figure 15.6 – Angioplasty and stent placement.

- Vascular surgery

- bypass surgery is the most commonly performed procedure

- indicated in those severely limited by IC, even after endovascular intervention

- autologous veins are used to create an alternative passage of flow

– aorto-bifemoral bypass: iliac artery disease

– femoral-popliteal bypass: superficial femoral artery disease

– femoro-femoral crossover: external iliac and unilateral common iliac artery disease

- bypass surgery is the most commonly performed procedure

- Amputation is performed in 25% of CLI patients, usually due to significant necrosis or paresis. Various options include:

- above-knee amputation: if the patient cannot walk or mobilise

- below-knee amputation: the preferred option due to the preservation of the knee and optimal functionality with lower limb prostheses

- mid-tarsal amputation: poor healing rates and functionality make this a secondary option.

- above-knee amputation: if the patient cannot walk or mobilise

Prognosis

- Over 5 years, 50% of patients with intermittent claudication will improve, 25% will worsen and 25% will remain the same

- Heart disease and stroke are the commonest cause of death in patients with peripheral artery disease.

15.2.2 Acute limb ischaemia

Definition

Sudden reduction in arterial blood flow to a limb.

Aetiology

- Thrombosis in situ (60%)

- thrombosis superimposed on an atherosclerotic plaque is termed ‘acute-on-chronic’ limb ischaemia

- it may also be due to an occlusion of a bypass graft

- in normal arteries, it may be secondary to underlying disease (e.g. thrombophilia and myeloproliferative diseases) and certain malignancies (e.g. pancreatic, breast and lung cancers)

- thrombosis superimposed on an atherosclerotic plaque is termed ‘acute-on-chronic’ limb ischaemia

- Arterial emboli (30%)

- atrial fibrillation (two-thirds)

- mural thrombus (one-third)

- atrial fibrillation (two-thirds)

- Other causes (10%)

- arterial dissection

- trauma

- external compression (e.g. entrapped popliteal artery).

- arterial dissection

Figure 15.7 – Pathophysiology of peripheral artery disease.

Clinical features

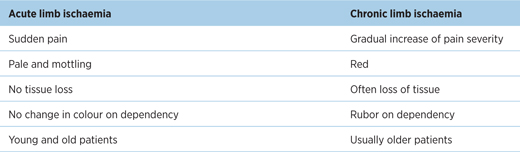

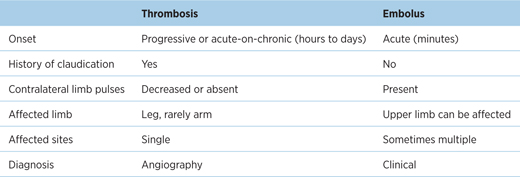

The clinical features of acute limb ischaemia should be distinguished from chronic limb ischaemia (see Table 15.2).

Table 15.2 – Differences in clinical features between acute limb ischaemia and chronic limb ischaemia

Furthermore, acute limb ischaemia secondary to thrombosis or embolism should be differentiated (see Table 15.3).

Table 15.3 – Acute limb ischaemia secondary to thrombosis and embolism can present differently

EXAM | Remember the 6Ps of acute limb ischaemia – Pain, Pallor, Perishingly cold, Paraesthesia, Pulseless, Paralysis |

Examination findings

- Differences in BP between arms or legs

- Signs of chronic ischaemia (see above)

- Buerger’s angle <20°.

// PRO-TIP //

Severe limb ischaemia is suggested if the leg turns pale when lifted higher than 20° (Buerger’s angle) and has a prolonged capillary refill time (>2 s).

Investigations

- Do not delay definitive revascularisation for diagnostic tests

- Duplex assessment to identify the site(s) of the occlusive vascular lesion.

Management

- General measures

- resuscitation: ABC

- involve the vascular multidisciplinary team

- analgesia

- position patient so feet are below chest level

– to maximise limb perfusion by gravity

- warm room temperature

– to prevent cutaneous vasoconstriction

- resuscitation: ABC

- Anticoagulation

- all patients should receive heparin

- Clot removal

- thrombosis: endovascular thrombolysis (see Guideline) or embolectomy

- embolism: embolectomy

- surgery if there is presence of motor/sensory deficit or if endovascular therapy is unfeasible

- thrombosis: endovascular thrombolysis (see Guideline) or embolectomy

- Revascularisation (thrombosis)

- once the clot is removed, the underlying arterial lesion should be treated as for chronic limb ischaemia. It is also indicated if there are continued symptoms despite thrombolysis.

- post-operative reperfusion injury (and subsequent compartment syndrome) is avoided by maintaining hydration and close observation

- once the clot is removed, the underlying arterial lesion should be treated as for chronic limb ischaemia. It is also indicated if there are continued symptoms despite thrombolysis.

GUIDELINES: Reperfusion therapy in acute limb ischaemia (ESC, 2011)

A combination of intra-arterial thrombolysis and catheter-based clot removal is recommended as immediate reperfusion in thrombosis. If this is not feasible, surgery is performed. There is no evidence to suggest one is superior to the other in terms of survival. Once the thrombus is removed, more permanent revascularisation is indicated. Systemic thrombolysis plays no role in acute limb ischaemia.

- Amputation

- for a non-viable limb or irreversible limb ischaemia.

Prognosis

- Poor long-term outcomes because patients usually have co-morbid cardiovascular diseases

- Risk of limb loss depends on the severity of ischaemia and time before revascularisation.

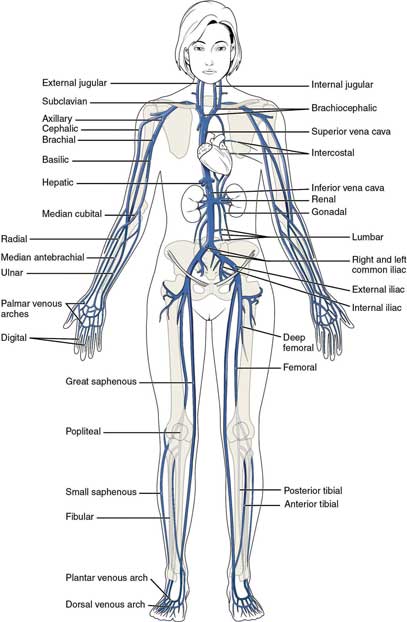

15.3 Peripheral venous disease

Chronic venous diseases consist of anatomical and functional abnormalities of the venous system, and include varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency.

Figure 15.8 – Venous system.

15.3.1 Varicose veins

Varicose veins In A Heartbeat

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree