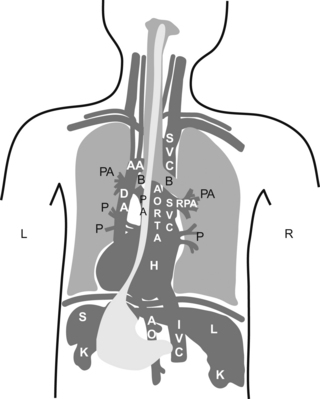

Chapter 10 Pericardium and Extra-Cardiac Structures Enrique Pantin and F. Luke Aldo There are so many things surrounding the heart that no one pays attention to! It is all about the heart though, so who cares about all that other stuff. Right? Wrong! L = left and R = right; PA = pulmonary artery, P = pulmonary veins, H = heart, L = liver, S = spleen, and K = kidney. In a transgastric mid-short-axis view below, we can see lots of stuff besides the heart! The Pericardium—we are back here again!

Anatomy and Pathology

The Pericardium

Surrounds, protects, supports, limits chamber dilation, and lubricates, allowing the free motion of the heart.

Surrounds, protects, supports, limits chamber dilation, and lubricates, allowing the free motion of the heart.

Provides entry and exit passages to the heart.

Provides entry and exit passages to the heart.

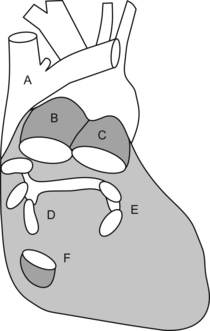

Is a medium-sized bag with lots of holes and tubes crossing it to enter or exit the heart:

Is a medium-sized bag with lots of holes and tubes crossing it to enter or exit the heart:

Upper abdominal aorta and its branches.

Upper abdominal aorta and its branches.

Trachea (yeah, we know you can’t see me but you know where I am because I don’t let you see other guys!).

Trachea (yeah, we know you can’t see me but you know where I am because I don’t let you see other guys!).

Spine, vertebral disks, and spinal cord (just bits of it can be seen).

Spine, vertebral disks, and spinal cord (just bits of it can be seen).

Stomach and its content or lack of it.

Stomach and its content or lack of it.

Other stuff like the tongue could be seen but it won’t be TEE but oral ultrasound!

Other stuff like the tongue could be seen but it won’t be TEE but oral ultrasound!

Starting from the esophageal entrance we can see the main neck vessels (the carotid arteries and internal jugular veins)

Starting from the esophageal entrance we can see the main neck vessels (the carotid arteries and internal jugular veins)

can be used to guide central line placement, though I would NOT recommend this in the awake patient!

can be used to guide central line placement, though I would NOT recommend this in the awake patient!

In the esophageal upper 1/3, we can see part or all of the arch vessels

In the esophageal upper 1/3, we can see part or all of the arch vessels

In the mid 1/3 of the esophagus, the trachea creates a blind spot, and we miss the distal ascending aorta, proximal arch, and proximal to mid left pulmonary artery, but we can see:

In the mid 1/3 of the esophagus, the trachea creates a blind spot, and we miss the distal ascending aorta, proximal arch, and proximal to mid left pulmonary artery, but we can see:

In the lower 1/3 of the esophagus, we can see:

In the lower 1/3 of the esophagus, we can see:

From the transgastric window we can see:

From the transgastric window we can see:

Did you understand the drawing?, I didn’t… If you didn’t, don’t kill yourself over it, it is a pretty bad drawing. My partner did the drawing, so call him and let him know you are happy he is a doctor and not an artist!

Did you understand the drawing?, I didn’t… If you didn’t, don’t kill yourself over it, it is a pretty bad drawing. My partner did the drawing, so call him and let him know you are happy he is a doctor and not an artist!

If you understood it, you are a genius!… then skip the following sentence. If you did not understand it, then continue reading and do as you are told. Go to your anatomy book and do a little review. Now pretend you are the esophagus and try to imagine how all of your neighbors look from where you are.

If you understood it, you are a genius!… then skip the following sentence. If you did not understand it, then continue reading and do as you are told. Go to your anatomy book and do a little review. Now pretend you are the esophagus and try to imagine how all of your neighbors look from where you are.

All potential spaces in the chest and abdomen (pericardial, pleural, abdominal, sub-diaphragmatic, and hepato-renal) have the potential for fluid accumulation.

All potential spaces in the chest and abdomen (pericardial, pleural, abdominal, sub-diaphragmatic, and hepato-renal) have the potential for fluid accumulation.

Depending on the location, amount, and speed of accumulation, it can present as a clinically silent finding on TEE or it can cause hemodynamic compromise.

Depending on the location, amount, and speed of accumulation, it can present as a clinically silent finding on TEE or it can cause hemodynamic compromise.

Fluid is usually seen as black on echo, but if the fluid has solidified, as in the case of clotted blood, it can look just as the liver or lung atelectasis does!

Fluid is usually seen as black on echo, but if the fluid has solidified, as in the case of clotted blood, it can look just as the liver or lung atelectasis does!

Gastric lining at the top, note the gastric rugae (those very tiny indentations in the very top of the echo image).

Gastric lining at the top, note the gastric rugae (those very tiny indentations in the very top of the echo image).

Pericardial reflection (that white line between “L” and the heart).

Pericardial reflection (that white line between “L” and the heart).

Moderate-sized focal image “C”, suggestive of clotted blood:

Moderate-sized focal image “C”, suggestive of clotted blood:

looks very similar to a layer of epicardial fat and can trick even the experts!

looks very similar to a layer of epicardial fat and can trick even the experts!

the history and additional findings will help define what the heck this is.

the history and additional findings will help define what the heck this is.

Right (R) and left (LV) ventricular cavities.

Right (R) and left (LV) ventricular cavities.

“Is there a pericardial effusion or not?” and if there is,

“Is there a pericardial effusion or not?” and if there is,

“Is there an aortic dissection?”

“Is there an aortic dissection?”

“Is there a clot in the pulmonary artery or other evidence of a pulmonary embolism?”

“Is there a clot in the pulmonary artery or other evidence of a pulmonary embolism?”

Is difficult to see by echo unless there is fluid on both sides of it or it is very thickened.

Is difficult to see by echo unless there is fluid on both sides of it or it is very thickened.

Can elicit some extra brightness on echo like it has its own light.

Can elicit some extra brightness on echo like it has its own light.

Has two layers (fibrous and serous).

Has two layers (fibrous and serous).

Serous layer has visceral and parietal aspects:

Serous layer has visceral and parietal aspects:

serous parietal layer is tightly bound to the fibrous pericardium that separates it from the rest of the chest structures

serous parietal layer is tightly bound to the fibrous pericardium that separates it from the rest of the chest structures

The layers extend a couple of centimeters, incorporating the aorta and main pulmonary artery.

The layers extend a couple of centimeters, incorporating the aorta and main pulmonary artery.

Confines the total volume the heart can handle at one time creating a closed volume relationship among all cardiac chambers.

Confines the total volume the heart can handle at one time creating a closed volume relationship among all cardiac chambers.

This limited volume relationship is the basis for the changes seen during effusions and restrictive or constrictive pericarditis.

This limited volume relationship is the basis for the changes seen during effusions and restrictive or constrictive pericarditis.

There is normally a bit of pericardial fluid or “oil” (normally 5 to 10 ml and rarely up to 50 ml) that lubricates the heart so it can dance without causing too much noise. Just like a car engine needs motor oil, so does the engine of the human body. Luckily, we don’t need oil changes every 3000 miles!

There is normally a bit of pericardial fluid or “oil” (normally 5 to 10 ml and rarely up to 50 ml) that lubricates the heart so it can dance without causing too much noise. Just like a car engine needs motor oil, so does the engine of the human body. Luckily, we don’t need oil changes every 3000 miles!

When the oil is too thick because the sac gets inflamed (pericarditis) or if the sac gets stiff, the pericardial layers rub as the heart moves and make some weird noises.

When the oil is too thick because the sac gets inflamed (pericarditis) or if the sac gets stiff, the pericardial layers rub as the heart moves and make some weird noises.

When the oil level is too high, we call this a pericardial effusion.

When the oil level is too high, we call this a pericardial effusion.

Several types of “oil” can fill the pericardial space:

Several types of “oil” can fill the pericardial space:

serum, sero-sanguineous fluid, blood, pus, solid things like metastatic tumors, fibrinous strands, etc.

serum, sero-sanguineous fluid, blood, pus, solid things like metastatic tumors, fibrinous strands, etc.

idiopathic causes, inflammation, infection, post heart attack, systemic conditions, malignancy, post trauma, surgery, radiation, congestive heart failure, etc.

idiopathic causes, inflammation, infection, post heart attack, systemic conditions, malignancy, post trauma, surgery, radiation, congestive heart failure, etc.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pericardium and Extra-Cardiac Structures: Anatomy and Pathology